|

|

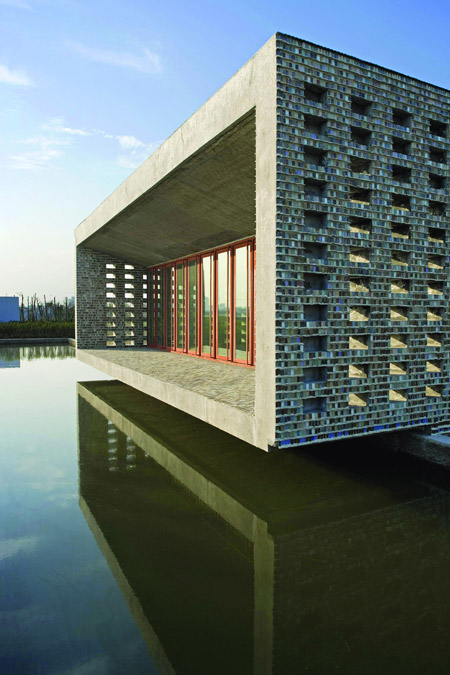

Ningbo History Museum, 2003-08, Ningbo, Zhejiang province The museum that presents the city's history is built on deserted docks from the bricks and stones of demolished houses. "Buildings aren't parts of the city - they're cities in themselves," the Pritzker prize-winning architect Wang Shu says. "I believe every old building is part of our heritage that deserves preservation." Photos by Lu Wenyu and Lu Hengzhong / for China Daily |

|

|

Library of Wenzheng College, 1999-2000, Suzhou, Jiangsu province The library sits between a lake and hills. Half the main building is underground and a quarter is underwater. |

|

|

Vertical Courtyard Apartments, 2002-07, Hangzhou, Zhejiang province This is Wang's only commercial real estate property development project. "My idea is that apartment buildings can be as close to the earth as courtyards," he says. |

|

|

Ceramic House, 2003-06, Jinhua, Zhejiang province The 100-sq-m teahouse is designed in the shape of a calligraphy inkstone. "A wonderful view matches wonderful tea," Wang says. |

|

|

Xiangshan Campus, China Academy of Art, Phase II, 2004-07, Hangzhou, Zhejiang province Wang collected some 7 million bricks and recycled them during the campus' construction. The campus has an academic building, fishpond, farm fields, bridges and dams. "My idea is that instructors, like Buddha, teach in the open air," he says. "People can realize free communication without boundaries." |

|

|

Wang Shu is the 2012 Pritzker Architecture Prize laureate. Zhu Chenzhou / for China Daily |

Pritzker prize-winning architect Wang Shu is training a new generation to respect

their surroundings and look to the past as well as the future. Wu Yiyao reports in Hangzhou.

At a campus setting of farmland dotted with ponds in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, youths drip with sweat as they saw wood and experiment laying bricks. The Architecture School of the China Academy of Art students are inspired by Wang Shu, the 2012 Pritzker Architecture Prize laureate (the first Chinese to win the award), who previously won the French Gold Medal from the Academy of Architecture in 2011 and the German Schelling Architecture Prize in 2010.

"I want to educate my students to become philosophical craftsmen, equipped with both thinking and technique," the 48-year-old head of the school says.

Wang believes this kind of training is preparing future architects to be sensitive to their surroundings and connected to the buildings they design.

Wang was inspired by his violinist father, a keen carpenter. "I was amazed at how great things could be created by deft hands," he says.

After becoming an architect, he looked at traditional Chinese methods of construction, which he characterizes as putting wooden blocks together, looking beyond the design of just a single building and taking the wider environment into account.

"We look around. We learn from other cultures and ignore our own architectural heritage," Wang says.

Unlike many of his peers, who went into real estate development after graduation, Wang spent 10 years studying anthropology, zoology, calligraphy and laying bricks. Instead of working on landmark high-rises, Wang preferred to deal with smaller scale projects.

His signature works integrate function and the building's surroundings. He set his library at Wenzheng College, in Suzhou, Jiangsu province, between the lake and hills. Half of the main building is below ground, while a wing extends underwater.

"A good reading place requires water," Wang says.

His Vertical Courtyard Apartments in Hangzhou feature spacious courtyards for gardens.

"When residents direct a guest to their apartments, they can identify their homes by the types of trees that grow on their balconies. They can say: 'I live in the place with peach blossoms'."

Wang's Ceramic House in Jinhua, Zhejiang province, is a 100-sq-m teahouse shaped like a calligraphy inkstone.

"I feel bad if I don't drink tea every day and a wonderful view matches wonderful tea," Wang says.

Wang says he is against high-rise buildings, and believes learning from the past is better than demolishing it and replacing it with something large and ugly.

"I love using traditional materials and building houses that look vintage," Wang says. "I am more interested in how people live in my buildings. When I say that I build houses instead of buildings, I am thinking of something closer to life - everyday life."

Wang's work transcends the debate between architecture anchored to the past and architecture that looks to the future by rooting itself in context and being universal, Lord Peter Palumbo, the Pritzker Prize jury chairman, says in his citation for the award.

A striking example is Wang's Ningbo Museum in Zhejiang's fast-growing coastal city.

Visitors to the museum sometimes break down in tears when they see that bricks and tiles from the demolished buildings of their youths have been integrated into the building's construction.

Buildings should be based on the connections among people, Wang adds, giving the example of China Academy of Art's Xiangshan campus, for which he widened the buildings' corridors, did away with many of doors and built pavilions.

"I was thinking of the college where Confucius studied and Greek philosophers chatted with fellow students - in this way, a campus dissolves boundaries and people can easily find one another and enjoy talking in open spaces."

Countering criticism from some students and teachers that they cannot find the classrooms and that they are too dark, Wang asks: "Why should we lock ourselves in classrooms to learn about painting trees and flowers when they are just outside the window?"

Another of Wang's ideas is to break down the boundaries on campuses among races, localities and time.

"Each culture, race and era are just a little bit different from one another, and these little differences may lead people to think there are more differences and seek clashes, simply because similarities haven't been stressed," Wang says.

He adds that his attitude was different as a young man. He attributes the change in his thinking to his architect wife, Lu Wenyu.

"She's tolerant of variety," he says. "She trusts me and supports me. And I truly believe at least half of my honors should go to her."

|

|

|

|

|

|