|

|

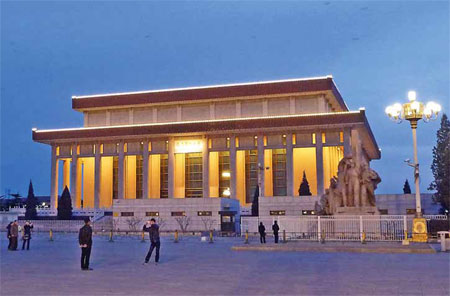

Mao Zedong Memorial Hall is a landmark in Tian'anmen Square, Beijing. Wen Bao / for China Daily |

|

|

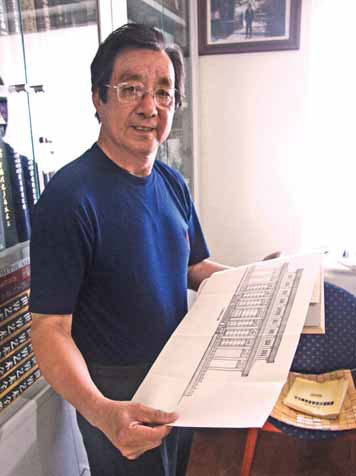

Architect Xu Yinpei shows off the mausoleum's blueprint at his home in the capital. Wang Ru / China Daily |

The man who led the construction of Mao Zedong's final resting place reveals his secret mission's details. Wang Ru reports in Beijing.

Xu Yinpei never imagined history would call on him.

But that's exactly what happened when Chairman Mao Zedong died in September 1976.

Xu, then age 39 and the deputy director of the Fourth Office of the Beijing Institute of Architectural Design (BIAD), was named chief architect of Mao's mausoleum and was given six months to complete the late leader's final resting place.

The State Council determined a plan to build a mausoleum after Mao's passing and founded the secret Ninth Office to select and supervise architects.

Xu, now age 75, was selected because of his incredible performance in enlarging the Tian'anmen Rostrum. The rostrum was expanded to hold about 400 political and military figures, including Mao's successor Hua Guofeng, at Mao's memorial ceremony, which was staged nine days after his death. About 1 million people gathered for the event.

"Although I wasn't interested in politics, I felt sorrow when I heard of Chairman Mao's death," Xu says.

"I never imagined I would be assigned such a difficult job. I felt so nervous because I only had three days to enlarge the rostrum."

Xu decided to build a platform and paint it red. Xu led workers from three factories in Beijing to race against time. "

It was hard to see from the outside that the rostrum had been enlarged," Xu says.

The Ninth Office was so impressed by Xu's work that it appointed him to lead the mausoleum's construction.

Xu, along with four other BIAD architects and more than 80 others from outside Beijing, moved into the Qianmen Hotel.

Ma Guoxin, one of Xu's BIAD colleagues, who was working on a residential construction project, joined the team.

"The project was initially secret," Ma recalls.

"So, many of the selected architects couldn't join the team until the office lowered requirements on their political backgrounds."

The first step was site selection.

Tian'anmen Square and Fragrant Hills were taken into final consideration.

"The Politburo Standing Committee finally decided to place the memorial in Tian'anmen Square because Chairman Mao should be remembered in the heart of the capital," Xu says.

"Someone proposed building the memorial at the square of Wumen (the Meridian Gate). That was immediately rejected, since it's said the place was used to execute senior officers in the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties."

Tian'anmen Square was enlarged from 110,000 square meters to 210,000 square meters, and transformed from a T-shape to a rectangle.

After the site was chosen at the square's southern end, architects began to work on drafts day and night. But the early blueprints resembled emperors' tombs, with solid aboveground constructions over underground burial chambers. "

The State Council said the memorial should be solemn, aesthetically pleasing and blend in traditional Chinese elements but shouldn't look like imperial emperors' tombs," Xu says.

"We weren't open-minded back then. Our inspirations were restrained by political ideology, and we had few chances to see buildings abroad."

It was rumored Mao Zedong Memorial Hall was based on the Lincoln Memorial. Xu insists this isn't true.

Xu visited the Lincoln Memorial when he went to the United States as a visiting architect in the early 1980s.

"When I saw the building, I said to myself: 'What a coincidence!'" he says.

The draft for Mao's mausoleum was finalized in October 1976.

It's a square hall with 44 granite pillars rising from a large burgundy granite base to support a golden double-eave roof.

The exterior and interior adopted traditional Chinese elements, such as the roof's chrysanthemum patterns.

Some designers had proposed drafts featuring political elements, such as slogans from the Great Leap Forward (1958-61) and "cultural revolution" (1966-76) periods, but all were rejected.

Xu recalls controlling the temperature was difficult. It needed to not only be comfortable for visitors but also preserve Mao's body.

"Only the former Soviet Union and Vietnam had such experience, but they refused to teach us," Xu recalls.

"Our air-conditioning technicians overcame the problem themselves."

The Beijing Municipal Construction Committee gave every architect a 20-yuan bonus, which was the equivalent of two weeks' salary for Xu.

"We debated fiercely as to whether or not we should accept the money," Xu recalls.

"Some said it was a mission of pure honor. Others said we should accept the money and frame it on the wall."

They ended up accepting the money and used it to purchase copies of the Mao Zedong Anthology to give soldiers.

"The atmosphere among the architects was pleasant. But some worried we would be buried under the hall as sacrifices - like the ancient laborers who built their emperors' tombs," Xu says, chuckling.

The groundbreaking ceremony took place on Nov 24, 1976. More than 700,000 laborers from around the country toiled to ensure the construction lasted only six months. The memorial hall opened on the first anniversary of Mao's death.

Zhang Runcang, now 73, joined the construction and says the scene was unforgettable.

"People from all over the country were eager to donate the best construction materials, such as camphorwood from the South or stone from Mount Qomolangma," he recalls.

Xu says: "When the memorial hall was finished, I ascended onto the Tian'anmen Rostrum - not to hear the crowd's overwhelming cheers but to see our work, inside which quietly rested a great Chinese man."

Contact the writer at wangru@chinadaily.com.cn.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|