|

Despite having heard stories about Japan's wartime atrocities, Iris Chang was overwhelmed when she stood in front of poster-sized images of the Nanjing massacre at a 1994 conference in Cupertino, California, sponsored by the Global Alliance for Preserving the History of World War II in Asia.

"Nothing prepared me for these pictures - stark black-and-white images of decapitated heads, bellies ripped open and nude women forced by their rapist into various pornographic poses, their faces contorted into unforgettable expressions of agony and shame," she wrote.

By then, she had graduated in journalism from the University of Illinois, where her parents were both science professors. For the next three years, the budding writer was to plunge into a history that constitutes one of the darkest chapters of World War II, and produced a book that is "almost unbearable to read" but "should be read", according to Ross Terrill, an Australian academic, author and China specialist.

Iris Chang began her research in the US. In the Yale Divinity School Library, she read the diaries of Wilhelmina Vautrin, also an alumnus of the University of Illinois.

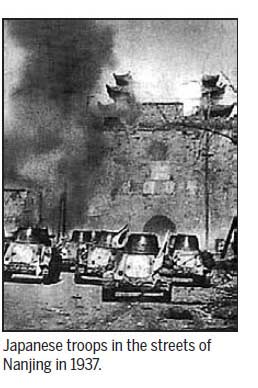

Born in 1886, Vautrin, a US missionary, was president of Jinling College in Nanjing at the outbreak of war in China. Turning the campus into a refugee camp, she helped save tens of thousands of Chinese, mostly women, during the massacre and afterward. "How ashamed the women of Japan would be if they knew these tales of horror," she wrote in her diary on Dec 19, 1937.

The stress took its toll, and having witnessed so much violence, Vautrin returned to the US in early 1940. On May 14, 1941, she took her own life.

Retracing old footsteps

Six months after reading the diary, Iris Chang was in Nanjing tracing Vautrin's footsteps, and discovering more about people and stories mentioned so frequently in the older woman's writings.

One of the interviewees was Li Xiuying, who was 18 years old and seven months pregnant in November 1937. She was stabbed repeatedly and was left for dead, until a fellow Chinese noticed bubbles of blood foaming from her mouth. Friends took her to the Nanjing University Hospital, where doctors stitched 37 bayonet wounds.

Unconscious, she miscarried on Dec 19, the day Vautrin made her diary entry.

"Now, after 58 years, the wrinkles have covered the scars," Li told Iris Chang, pointing to her own face, crosshatched with scars.

During her visit to Nanjing, Iris Chang was deeply disturbed not only by the inhumanity of war, but also by what she saw as a failure to mete out appropriate justice, according to Yang.

One of the survivors they visited lived in a room no more than six square meters. The old man was bathing, and the water in the small basin had almost turned muddy. "The way Iris moved her video camera - from the low ceiling to the soot-covered walls and the rubbish-clogged corridors - clearly indicated her mood," Yang said.