Root causes

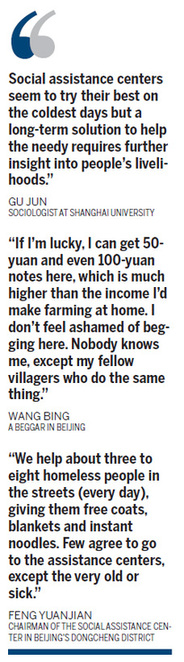

The issues fueling homelessness in China are far too deep-rooted to be solved with a hot meal and a ticket home, according to experts, who say the widening wealth gap and general living conditions in the countryside are main culprits.

This problem exists all over the world "but the rich-poor polarization and the backward rural social security system" are major factors in China, said Hu Xingdou, an economist at Beijing Institute of Technology.

He Feng and her husband, both 55, hail from a rural area of Shangqiu, Henan province. At 11 pm on Dec 15, they had just finished another day of begging at Beijing Railway Station.

"My husband suffered a leg disability and lost four fingers on his right hand in a car accident," said He, who was laying with her husband covered by a thin, dirty quilt. There was a crutch next to them on the ground.

She explained that they came to the capital in 2007 because their farm was unable to grow enough food for the family, and that they had never received a subsidy from the government. Their son, she said, is 36 and works in Shanghai on construction sites.

"I know about the assistance centers but we have to be in the street because we live on begging," said He.

Less than five minutes after talking with China Daily, the couple packed up and took the escalator to the station's second floor. He's husband walked smoothly, carrying the crutch in a right hand that had all five fingers.

Beggars often pretend to be disabled, said Pang Yanshen, a 48-year-old worker at the Dongcheng center, who can recount stories of finding a "wheelchair-bound man running" and a "deaf women chatting freely with a friend".

According to Feng, who has run the Dongcheng shelter since it opened in 2003, most beggars actually come from a small number of villages.

He said that, during a conversation with an official with Minquan county's civil affairs bureau in Shangqiu (He Feng's home city), he discovered that many villagers took to begging after hearing at Spring Festival how much money their neighbors had made on the streets.

Wang Bing, a 52-year-old from Minquan county, begs most days under a flyover near the capital's bustling Sanlitun shopping area.

"If I'm lucky, I can get 50-yuan and even 100-yuan notes here, which is much higher than the income I'd make farming at home," he said. "I don't feel ashamed of begging here. Nobody knows me, except my fellow villagers who do the same thing."

Like many others, Wang also refused help from the assistance center workers - unless they were willing to provide him with a ticket to Shanghai. In his mind, the streets of big cities are paved with gold.

"The fact some people prefer to migrate and eat leftovers in the capital proves there is an excessive concentration of power and money here," said Zhou Xiaozheng, a sociologist at Renmin University of China. "We have a rich country now, but the people at the bottom of society are still living miserable lives."

Pensions plan

Dealing with the conditions in the countryside could go a long way to reducing the number of homeless people in the cities.

In some impoverished rural areas, where even basic transportation is undeveloped, it can be difficult for families to improve their living standards, making begging an attractive option.

"If villagers led decent lives at home, they wouldn't come (to cities) to be looked down on by others (as beggars)," said Xia Xueluan, a sociologist at Peking University.

He suggested assistance center should run courses that boost the knowledge and skill bases of "those who have the ambition to be self-reliant, which would at least give them equal opportunities" to find work.

A 60-year-old woman who gave her name as Wang said she moved to the capital five years ago from Shuozhou, Shanxi province, after she was abandoned by her only child, an adopted son. She now survives by collecting empty bottles in and around Beijing Railway Station.

At about midnight on Dec 15, she had just found a seat in a warm waiting room and had successfully avoided a ticket check by police.

"I only earn about 3 yuan during the frosty weather," she said, as she ate from a plastic bag of leftovers she found in a trashcan. "There are more drink bottles in summer and I can make up to 10 yuan every day then."

When asked if she was willing to visit an assistance center, she replied: "I'm all on my own. I don't want to go home. My life there would be no better than here."

Experts say her case highlights serious flaws in social security in rural areas.

The government unveiled a new countryside endowment insurance program last September, which grants a minimum of 55 yuan a month to villagers over 60. However, it is still at the pilot stage and will not be rolled out nationwide until at least 2020.

"Needless to say, (people in) other places don't even have (access to) pensions," said Hu Xingdou of Beijing Institute of Technology.

According to Hu's calculations, just 300 billion yuan a year would be enough to pay pensions of 200 to 300 yuan to every person above the age of 60 nationwide.

China, which has an annual revenue of 6.85-trillion-yuan can afford that, he said.

To ease the burden of homelessness, officials nationwide are also being encouraged to find new ways to increase farmers' incomes and narrow the urban-rural divide.

Experts anticipate a further reform of the land system, which should enable farmers to make profits, rather than allow local governments to benefit from land contracting and development.

In addition, authorities should push more insurance companies to offer services to rural customers, a market that few are currently interested in since compensations for injuries or death far outweigh potential revenue.

"This could at least guarantee (villagers) basic living costs in case they encounter crop failure or housing collapse," said Hu.

With more security in the countryside, experts say fewer people would be inclined to take a risk on city streets.

Zhang Xiaomin in Dalian and Wang Hongyi in Shanghai contributed to this story.