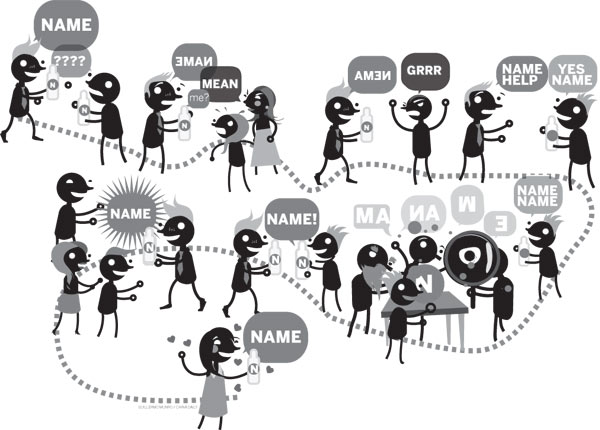

Nothing's lost in translation. In fact, the Chinese names of international brands in China give new meanings to the original nomenclature. Erik Nilsson shows you some examples.

A white-collar Chinese urbanite might chat on his "Orion's Belt" while steering his "Precious Horse" toward a burger at the nearest "Grain at Toil". In other words, he might talk on his Samsung (sanxing) while driving his BMW (baoma) to McDonald's (maidanglao).

While these brand names' literal English retranslations sound amusing - or bemusing - to native speakers, they ring like music to the Chinese ear.

|

Multinational corporations have long been playing a name game to ensure their brand identities are not lost in translation when they enter China. Today, domestic enterprises are following suit as they become players in overseas markets. Consequently, demand for enticing English brand names is growing.

A scientific business has been devised around translating MNCs' names into Chinese - one in which perhaps thousands of proposals are developed before specialized consultants squeeze them through computer programs, multi-dialect linguistic analyses and focus groups to extract the best option.

But most Chinese enterprises aspiring to penetrate overseas markets simply ask their marketing teams to stab at something they hope works in English.

|

Rather than crunch out quantitative and qualitative analyses, Wang usually hunts for transliterations (translations with similar pronunciations to the originals) that generate positive associations. Or he scours the Bible or Greek mythology for names with historical zing.

He recalls selecting the English name for Chinese auto parts manufacturer Xinshiji, which literally translates as "New Century".

"New Century is widely used and isn't appealing enough," Wang says. "So, I gave the company the English name 'Synsky'. It's a similar pronunciation as the Chinese, and the prefix 'syn' suggests the company and its consumers share the same sky."

Globao senior consultant Amy Chen says her company will suggest English names for clients, but most will decide for themselves.

"These companies usually already have a clear idea of the name they'll use abroad," she says.

Chinese Translation Pro senior translator Yao Zhang believes: "Chinese companies don't seem to put as much weight on, and resources into, branding as Western firms, and are generally content with average English brand names."

Yao's company has translated the names of such juggernauts as Dow Chemical, General Motors and L'Oreal, but has never translated a brand from Chinese into English. Most domestic companies don't bother to translate their names.

Beijing entrepreneur Cheng Wei is CEO of both Beijing Shuilan Technology Ltd and Kaixin Yinfu music school. The growing music school has directly translated its name as "Happy Notes", despite not yet enrolling foreign students.

But Shuilan, which would literally translate as "Water Blue", hasn't conceived an English name although it contracts for Fortune 500 clients, such as BMW.

"We never thought about translating Shuilan because we deal with multinationals' China operations," he says.

However, Chinese companies that directly market overseas often discover that it's advantageous to translate their names. Some contend domestic soft drink brand Jianlibao, which literally translates as "Health Strength Treasure", fizzled outside China because consumers couldn't pronounce it.

Perhaps because Chinese companies are rupturing their national boundaries later in the game, their brand-name translation systems hail to the era when foreign companies started penetrating China.

Some translations from that era ranged from hilarious to harrowing. KFC's "finger-licking good" translated as "eat your fingers off", Time magazine reports.

"Come alive with Pepsi" was translated as "Bring your ancestors back from the dead", CNN says, while Coca-Cola's name was initially translated as "Bite the Wax Tadpole", language-study magazine The World of Chinese reports.

When that failed, Coke switched to "Wax Flattened Mare" and then arrived upon "Delicious and Happy (kekou kele)".

For Coca-Cola, it was a process that passed through names that sounded like nothing anyone would want in his mouth to a potion that everyone wanted to guzzle. The company had copious translation options, which would today be scientifically scrutinized in the sophisticated English-to-Chinese translation business.

As J.A.O. Design International Architects and Planners Ltd CEO James Jao puts it: "You don't want to be a laughingstock."

Taiwan's Economic Daily News this year awarded Jao's Chinese branding - Long An - as the Most Recognized Brand in Chinese Real Estate for the fifth year and third in a row.

Jao was born in Taiwan, gained US citizenship, studied marketing and became New York City's planning commissioner. He came up with "Long An" - a transliteration of Long Island that means "Peace Dragon".

J.A.O. Design not only scientifically scrutinized the name but also hired a geomancer to determine its auspiciousness according to its stroke number when written in traditional Chinese characters.

The flipside of the name's success, Jao says, is that 15 companies have copied it.