|

Cheezheng Tibetan medicine factory in Linzhi, Tibet. |

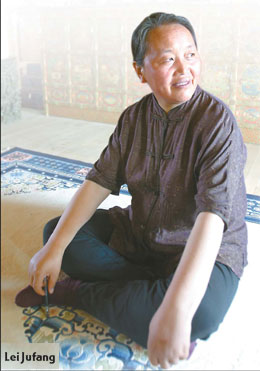

As Lei Jufang crosses the noisy street in a Beijing neighborhood dominated by embassies, five-star hotels, and big name companies, she carefully scans the heavy traffic, and holds the hand of her assistant, who looks like her daughter.

With no makeup and her graying hair combed into a plait behind her, 55-year-old Lei, dressed in a plain black shirt, looks like a middle-aged woman shopping for vegetables in a market. Yet she is anything but an average housewife.

She is board chairwoman of China's largest maker of Tibetan medicine, Cheezheng, and before that she was a physics engineer and winner of national science awards.

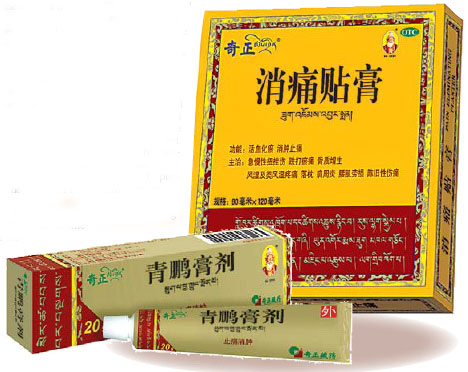

In fact, she is the creator of Cheezheng, a brand name Tibetan medicine used for skin injuries. Cheezheng pain relief plaster now ranks the first in the domestic market among similar products. With annual sales of over 400 million yuan, products from her company are seen in most pharmaceutical stores in China, and its users range from ordinary folks to Olympic athletes.

Yet as people praise her for making medicine accessible outside Tibet while contributing to local GDP growth, Lei is doubtful. "Isn't it good to leave it there for those who invented it?" she asks.

It seems there is always a dilemma in her life. Describing herself as an idealist and citing Joseph Needham, the respected British scholar and the author of Science and Civilization in China, as her career inspiration, she says she was meant to be a scientist, not a profit-driven businessperson.

Born and brought up in poverty-driven Gansu province in northwestern China, Lei says the memory of poverty has never really left her. She always makes sure that the plate in front of her is empty after a meal, and suggests that others do the same. For her, waste is like committing a crime.

Fortunately, her hometown had a tradition of sending children to school - no matter how poor they were - and the diligent and hard working Lei was able to go to college to study physics.

She graduated and worked in a science academy in Lanzhou, capital of Gansu. As an assistant professor, she worked out a way to use a vacuum seal to preserve materials such as food - a technology that European scientists refused to transfer to or share with China at that time, she recalls. She was rewarded with fame and money, and a possible promotion within the organization she worked for. But one thing kept puzzling her: what is the meaning of all the hard work if many scientific results remain in the laboratory?

In 1987, as the government was encouraging privately owned businesses, Lei left the institution and started her own science institution focusing on the treatment of industrial pollution - a fashionable business in China now but often misunderstood by people then.

For the past 30 years, GDP increase has always been the top priority in China's economic development, and damage to the environment did not draw people's attention until recently. People now praise Lei's foresight in the 1980s, but she almost lost her new business as few valued her work 20 or even 10 years ago.

"That is a mistake committed by a foolish idealist," says Lei. "I think it is important to waste less and improve the environment, but nobody else wanted that at that time."

The failure of doing business also made her wonder about the true meaning of life. "I started to ask some basic questions, " she says. "For instance, 'what is true in life?'"

The questions drove her to a soul-searching journey to Tibet, a place that she had always wanted to see. There she found the power of religion remains strong and began to learn more about Tibetan Buddhism.

Lei went back to Tibet several times afterward. Learning from lessons of her first business experience, she thought that maybe a good way to do business was to create something that people are seeking for their own good, not others. "People will buy medicine that is good for themselves, but not for others," says Lei.

And she also remembers that when she visited a Buddhist temple in Tibet, she saw a picture on the wall with a drawing of the structure of human body. The structure was as precise as any modern medical school, but it dated back to as many as 200 years ago.

The lesson and the Tibetan medicines that she learned about from these journeys made the medicine business an obvious choice for her when she considered the next step after the failure of her first attempt.

But a difficulty is that despite the proven effects of Tibetan medicine in treating certain diseases, they don't last long as herbs, the major component, are difficult to preserve. And it also explains why Tibetan medicine has never really left Tibet, or why it has never been made and processed in an industrialized way.

Fortunately, technology and invention are Lei's strong suits. And her background in vacuum seal preservation allowed her to invent a packaging machine herself rather than trying to buy one for millions of yuan from another country.

The second problem was how to promote her new product. Lei adopted a grassroots, word-of-mouth approach and sent her staff, most of whom stuck with her after their first failure, free Cheezheng medicine. They persuaded some of China's Olympic athletes to try the products and also sent some to friends and relatives.

Lei recalls that they sent out medicine worth tens of thousands of yuan, a huge cost for a startup company. But the immediate loss paid off with quick fame. Praise from Olympic athletes who used the medicine to treat injuries drew interest. The media came and Lei and her company were soon in the limelight.

Today, she employs over 1,000 people, and 98 percent of them are local Tibetans. Lei says sometimes she has doubts about whether her Buddhist belief is contrary to pursuing profits.

"I was told that as long as your motivation is good and you put your money to good use, it is fine," she says. As a result, she is investing a large portion of her money to local Tibetan education, to encourage young Tibetan children to become doctors.

"According to Tibetan medical theory, doctor and medicine can never be apart from one another, " she says.

In fact, there are fewer practitioners of Tibetan medicine now. With an aim to make her business sustainable, Lei has also planted a 3,000-meter-high herb plantation of Tibetan herbs for future production.

Lei says her biggest enjoyment is found in worshipping at Tibetan Buddhist temples. She also plans to work less in a year or so and turn over the management of her company to the young people around her.

"I will have more time to worship after I retire," she says.

(China Daily 06/30/2008 page12)