|

|

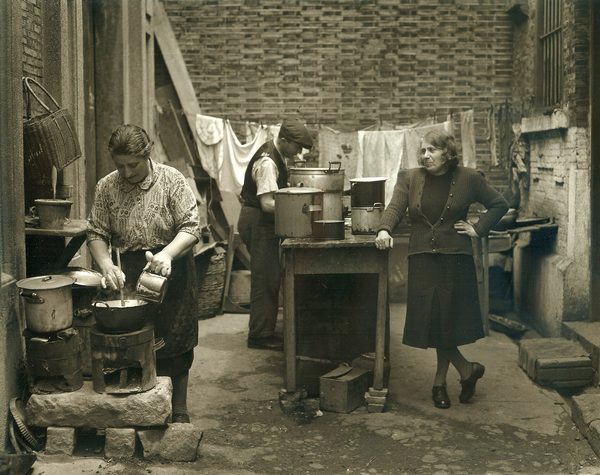

A woman uses a small Shanghai-style coal-fired stove to cook food in a courtyard kitchen. Provided to China Daily |

A story to share

Built in 1907, relocated to the current location in 1927 and renovated with special funds from the district government in 2007, the synagogue-turned-museum received more than 40,000 visitors last year, 55 percent of them from overseas."To be a tour guide in this museum is to be an accumulator of stories, stories buried but not forgotten," said 66-year-old Wang Yaohua, who for the past decade has guided visitors around the exhibits. "People come because they are interested, and there's often a definite reason behind that interest," he said. "Usually, a person won't let it show in the beginning. But as they view the black-and-white photos, a well-kept Torah, or a handmade chair in the typical Alpine style, you can sense the emotion welling up behind the calm facade, and sometimes you just know that person has a story to share."

A few years ago, Wang met a man who as a boy lived with his refugee family in an attic on the fourth and fifth floors of the synagogue. "The family was allowed to live there because his father ran errands for the elders. He was so thrilled to find some of the family's old furniture still there," said Wang.

The communal spirit helped, according to the former refugee. "The Jewish people were very much bound together," he said, referring to the crucial help given to refugees by co-religionists who had arrived earlier, including food, shelter and medication. "On summer nights after 7 pm, all the Jewish people in our neighborhood would come out onto the street. They listened to music, sipped coffee and chatted - information was exchanged that way."

Wang said the museum is playing an essential role in keeping the past alive. "At our museum, people revisit their parents, relatives and friends pasts, and even occasionally their own. They've contributed to the preservation of this past by sending us whatever has remained with them that could be woven into the narrative of this 'Once Upon a Time in Shanghai' story."

On Dec 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, before declaring war on the Allies. The events had huge implications for Shanghai's Jewish residents. "Japan's alliance with Germany automatically increased the danger posed to the Jews," said Wang. "On Feb 18, 1943, the Japanese authorities declared a 'Designated Area for Stateless Refugees', ordering all those who'd arrived after 1937 to move into a an area of less than 2.5 sq km in the southeastern part of the Hongkou district. For the refugees who'd found a means of livelihood outside the designated area, leaving their homes and businesses behind for the second time was traumatic."

The area, known as the Shanghai Ghetto, had no barbed wire or walls, but the streets were patrolled, food was rationed, a strict curfew was enforced, and everyone needed passes to enter or leave. "Of the 14,000 Jews living inside, only about 3,000 were given passes between 1943 and 1945," Wang said.

Acquisition of a pass might subject a person to humiliation by Mr Goya, the Japanese head officer and self-proclaimed "King of the Jews", recalled Harold Janklowicz, during an interview for the 2002 English-language documentary film Shanghai Ghetto. "Mr Goya was a very short, little man, and my stepfather, Werner, was a very tall man. The little man didn't like that. He jumped on the table and slapped him across the face, and yelled at him to get out and said 'No pass'," recalled Janklowicz. "I remember Werner coming home that day and he was a shattered, broken man."

Even after all these years, Chen still ponders one question. "Why didn't the Japanese kill the Jews? That's an inevitable question with open answers," he said. "One prevalent view is that the Japanese didn't want to antagonize the Jews because they were thought rich and powerful."

"All I can say with certainty is that while the Japanese, in not slaughtering the Jews, were carrying out a well-calculated governmental edict, the local Chinese, in living with and befriending them, were acting out of natural sympathy," he said.

Zhang Jian, deputy director of the Institute of History, Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, said: "For Jews living in Continental Europe, the candles of hope had been snuffed out one by one since 1933, the year the Nazis came to power. Synagogues were burned, Jewish shops were wrecked, assets confiscated and men thrown into concentration camps."

|

|

| Weihsien: Life and death in the shadow of the Empire of the Sun | In memory of unnamed war heroes |