An economic agenda for Italy

Despite positive developments, the road ahead is bumpy. Navigating it will require Italy to retain its credibility with other European Union member states and international investors. The new prime minister will need to persuade Germany, financial markets, and the European Council that Italy is a reliable partner.

The ability to refinance government debt and keep costs down is essential to strengthening public finances and boosting GDP growth. Furthermore, attracting more direct investment is crucial, given that capital inflows, while recovering, remain 30 percent below their pre-crisis level; with outflows exceeding inflows, Italy has become a net capital exporter.

"Selling" Italy in Europe should entail more than photo opportunities with other leaders in Brussels and the occasional road show to financial institutions in London. Italy's leaders should engage actively in commercial diplomacy, using the country's embassies and trade agencies to promote Italy globally, while working to build strong bilateral relations with other EU members, particularly southern countries like Spain.

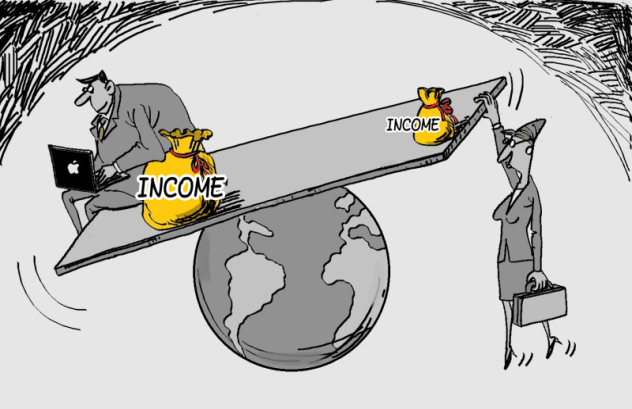

At the same time, the new leaders need to "sell" Europe in Italy, where euro-skepticism is rampant. According to the Pew Research Global Attitudes Project, only 30 percent of Italians view the euro positively. In the country's wealthier north, where average per capita income, at 30,000 ($40,500), approaches that of Germany, people are questioning the rationale of EU membership. The costs are evident, they argue, but what are the benefits? Meanwhile, fears of structural decline pervade the country.

The crisis has lasted for a long time, and people are tired. Unemployment has risen to a record 11.2 percent, with 35 percent of young people jobless. And the tax burden, which has exceeded 40 percent of GDP since 1990, now stands at almost 43 percent of GDP.

A Scandinavian level of taxes would be bearable if public services did not remain inferior to those offered in Scandinavia. For example, per capita healthcare spending in Sweden, Denmark, and Finland exceeds $3,000, compared to only $2,300 in Italy, where households must contribute roughly 20 percent of total healthcare spending.

Moreover, Italy spends around 4.5 percent of GDP on education, while the Scandinavian countries spend more than 6 percent of GDP. As a result, Italian students' scores in the Program for International Student Assessment are significantly lower than those of their counterparts in many other OECD countries.

Italy's new government will have to display leadership and vision to guide the economy toward stable growth, avert a race to the bottom, and stem growing social tension. Most important, economic renewal depends on the next government's willingness and ability to address the institutional weaknesses that have made concerted action increasingly urgent.

Project Syndicate

The author is research director of International Economics at Chatham House.

(China Daily 02/21/2013 page9)