Waste not, want not

Experts say improving the poor sanitary facilities in the country's rural areas through the use of eco-friendly toilets will raise residents' standards of living and protect the environment, as Yang Wanli reports from Changshu, Jiangsu province.

Compared with many of his middle-aged peers, who are conventional and wary of new developments, Wang Yuanyuan is an exception. In the early 1990s, the 67-year-old farmer was the first to install a flushing toilet in his home in Chentang, a village in Changshu city, Jiangsu province. Decades later, Wang again was at the forefront of another ecologically friendly sanitary revolution when he purchased a vacuum toilet.

In January 2011, with the help of an expert team from Beijing, Wang's family became the first in Chentang to experience the "high-tech" toilet, which is made of white porcelain and looks no different from the regular thing.

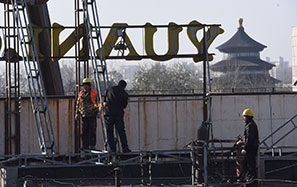

|

Vacuum toilet system designer Fan Bin aboard a "night soil boat" in Chentang village, Changshu, Jiangsu province, on Dec 3. The boat carries the waste from several riverside villages to farmland where it is used as fertilizer. Photos by Yang Wanli / China Daily |

"But it only uses 5 percent of the water required by a normal flush toilet," Wang said. In his 3-square-meter bathroom, the old and new toilets stand face to face. At first glance, apart from the wooden seat on the old toilet, the two are almost indistinguishable, but the new toilet has a completely different sewage system than its predecessor.

In China's urban areas, flush toilets are connected to underground sewers, but in the rural areas, there is no such network. Even with the same type of flushing toilet, the sanitation system in Wang's house operated differently than those in modern apartments in cities because all the waste was simply carried into a large hole next to the house. In 1994, when it was installed, the system - a flush toilet, a cement hole and several connecting pipes - cost 2,000 yuan ($312), equal to about half of China's per capita GDP that year.

The decision meant that Wang's family no longer needed to use the public toilets like the other residents, but it also had a downside; he had to empty the cement hole - the storage pit - once or twice a week. Moreover, because it was just outside the window of the main living room, had to make sure he covered it carefully. "Otherwise, the awful smell would be really disgusting, especially during summer," he said.

All that ended in spring 2011, when Wang bought the vacuum toilet. Essentially, the appliance is hooked up to a vacuum sewer system, and when the flush button is pushed, a valve opens and the contents of the toilet bowl are sucked into a special storage container.

"There is no bad smell at all," Wang said. As a farmer, he is extremely satisfied with the toilet's ability to collect human waste, which can be used as fertilizer on his fields.

"Rice seedlings nourished by the human fertilizer grew higher than those grown with chemical fertilizer, and the rice tasted sweeter," he said. He added that he had sent the rice to the provincial agriculture products testing center, where the lack of chemicals used in cultivation resulted in it being classified as organic produce.

Avoiding health risks

Vacuum toilets have been used by commercial airlines for years, but now they are being used in large-scale residential sanitation in China for the first time. "Unlike normal flush toilets which work via gravity, the vacuum toilet has pipelines that can be designed according to the structure of the building. That makes installation easy, even in the old residential areas," said Fan Bin from the Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Fan initiated the sanitation project in Chentang. Having been born and raised in a similar village, he has a deep conviction that it's time for a sanitation revolution in rural China.

Dry toilets, both the public and private varieties, are still abundant in the villages of rural China - large, open pits covered by a rudimentary shelter, with a narrow cement or wooden platform for standing or squatting.

In this traditional sanitation system, no water is needed and the waste can be taken out every day for use as fertilizer. The system is eco-friendly, but inconvenient and dangerous - as evidenced by countless stories of children or seniors who have slipped and accidentally fallen into the hole. Moreover, the pits pose a health problem because of the smell and the potential to spread disease.

In 2011, the world's biggest private foundation - The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation - launched the "Reinvent the Toilet Challenge" to encourage a global search for innovations that would prompt next-generation sanitation. "It inspired me to promote a pilot project in rural areas, so I began designing a system with a vacuum toilet that would be suitable for China's rural areas," Fan said.

Using Fan's design, 41 vacuum toilets were installed in 23 houses in the Hehuageng district of Chentang. The toilets are connected to an electric-powered vacuum-assist system that conveys the waste to an underground storage tank where it is separated for use as solid and liquid fertilizers. Tubes connected to the tank spray the liquid fertilizer directly onto farmland about once a month, while the solid waste is emptied once or twice a year and is also used as fertilizer. A technician visits regularly to check performance and safety features, but only a couple of small problems have been reported in the past four years.

The entire system costs about 20,000 yuan per family, but according to Fan, if it could be produced on a larger scale, the vacuum toilet could be far cheaper than the flushing models, not to mention the environmental benefits. "That's why I'm calling for widespread use of this technology in rural areas to keep the cost low," he said.

The system works well, according to Fei Xiaoliu, 56, who has installed a vacuum toilet in her house. "Many people from other residential areas came to visit our new toilet. Almost every person asked how they could get one. It's not troublesome at all because it doesn't emit bad smells," she said.

Pilot project

The pilot project in Chentang is just one of a number of sanitary-improvement projects tried in China in recent years. Early in 2004, the Stockholm Environment Institute from Sweden provided the Inner Mongolia autonomous region with the world's largest urban installation of urine-diversion dry toilets.

The toilets, provided to more than 800 families in Erdos Eco-Town and funded by the local government, were designed to separate liquid waste from solids. The bowl had two sections, one at the front for urine and a larger one at the rear for solid waste, so the waste never mixed.

After a five-year trial, the project was discontinued; the residents complained to the media about the terrible smell and said the bowls often needed to be repaired. Although experts from the institute checked the program and suggested ways of resolving the problems, the local government and the residents decided to withdraw their support, fearing they would lose money in the long-run.

In June 2009, the local government funded a return to flushing toilets and the eco-toilet project was officially canceled.

"It is an excellent illustration of the best of intentions, but flawed in practice," Fan said, adding that vacuum-sanitation technology is the best way to provide modern sanitary facilities in rural areas and ensure sustainable development.

Fan's design uses a minimal amount of water, just 0.3 liters per flush, about one-tenth of a conventional toilet. "People had got used to using flushing toilets and believed the toilet would be cleaner with water. That's why I didn't remove the water flushing function in my design," he said. "Ideally, the most-suitable system for China, especially the rural areas, should not be too complicated and the components must be robust."

In the eyes of people who have devoted themselves to recycling human waste, the sanitation solutions will benefit the environment and help sustainable human development.

Experts around the world are working hard to provide solutions to environment pollution, especially the increasing damage that human activities are causing in water systems, said Zhang Jian, president of EnviroSystems Engineering and Technology Co, a company in Beijing focused on vacuum-drainage technology, and sewage and waste.

Zhang said human waste contributes more than 90 percent of the nitrogen and phosphorus released into the world's lakes, rivers and oceans. Scientists are now tackling the two elements as the main focus of their work.

Too much nitrogen and phosphorus in the water causes algae to grow faster than ecosystems can handle, damaging the water quality, food resources and habitats, and depleting the oxygen that aquatic life needs to survive. Some algae blooms also produce elevated levels of toxins and bacterial growth that can cause a range of illnesses, some serious, in humans.

"Nitrogen and phosphorus are like two drops of ink. Other human wastewater, such as that used for washing clothes or bathing, are much less harmful and can be described as 'clean' water," Zhang said. "But if we expel the 'two inks' through the underground drainage system into the large pool of 'clean water', it's extremely difficult to remove those two drops."

In 1985, Zhang moved to Germany, where he spent 10 years researching how developed countries treat the burden human waste imposes on the environment. "I finally realized that the situation in China is absolutely different," he said.

Western Europe and North America have had mature underground drainage systems for centuries, and many countries in those regions are facing negative population growth, thus relieving the burden on their sanitary systems. "To achieve source separation (preventing liquid and solid waste from mixing in the sewage system) would cost too much money and effort. So those areas focus on garbage recycling rather than the toilet revolution," Zhang said.

In 2003, he started work on an eco-toilet that could achieve source separation. His design is as similar to Fan's, but is supported by a solar-powered vacuum assist.

Fan's next plan is to install a type of vacuum trash can in the houses in Chentang and link them to the existing system. The design will mainly be used to collect kitchen waste, which can be mixed with human waste to ferment and be used as fertilizer.

"If kitchen waste is removed from domestic solid waste, the cost of waste treatment in the rural areas would be cut by about 80 percent," he said. "The biggest challenge we face is not related to technology, but whether the government values the potential benefits and supports and promotes the idea."

Contact the writer at yangwanli@chinadaily.com.cn