Time to embrace a shared vision

The world's largest developing country and biggest bloc of developed countries need to deepen their strategic partnership

Many Europeans believe that China, one of the European Union's 10 so-called strategic partners, behaves more like a competitor. And many Chinese, for whom the EU is just one of more than 70 strategic partners, complain that the EU's policy toward China is more commercial than strategic.

Such grievances are rooted in different interpretations of the nature and purpose of strategic partnerships. Where China sees an enduring, comprehensive, and stable relationship that extends beyond everyday issues, Europe sees market access and better global governance, but lacks a clear long-term vision for the partnership. Unresolved issues - for example, the EU's embargo on arms sales to China, its unwillingness to grant it market-economy status, and the recent anti-dumping and countervailing-duties cases it has brought against the Chinese - have aggravated these divergent perspectives.

For China, the value of a partnership with the EU lies in three main areas. First, it offsets "Americanization" - that is, the influence of the United States over global economic development, and the spread of the US lifestyle and mentality. The EU's global influence - won through its peacekeeping missions, diplomatic efforts, aid provision, and non-traditional security mechanisms - counterbalances US domination over the international community.

Second, the EU, with its technical, financial, and market strengths, is China's largest trade partner and a major source of technology transfer. It has respected China's values, while sharing knowledge, skills, and innovations that support China's modernization and efforts to increase domestic demand.

Finally, the EU's emphasis on harmonious development has served as an example for China's peaceful rise. Indeed, China's 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-15) shares some features with the EU's Horizon 2020 strategy for sustainable, smart, and inclusive growth.

But the EU lacks a coherent strategy for engaging with China, and its ongoing identity crisis over whether it is a single super-state or a bloc of individual states is impeding its ability to define a more effective approach.

As it stands, China-EU relations are based largely on economic and trade linkages. But these connections are unlikely to develop further in the foreseeable future, given weakening EU demand. Moreover, while some EU countries, such as Germany, benefit significantly from China's economic development, others view competition from China as problematic.

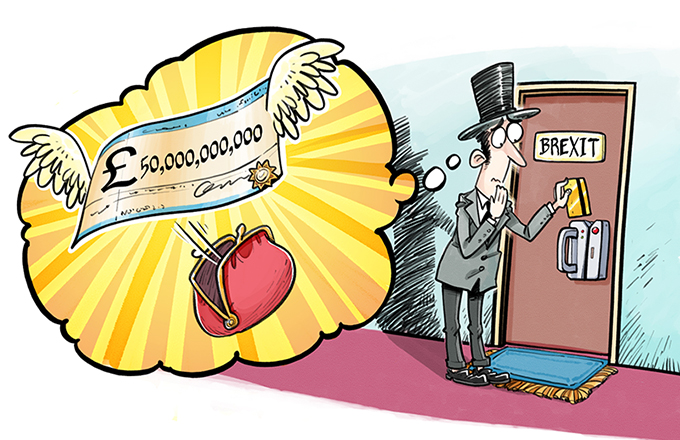

The partnership's limited strategic dimension largely reflects the concerns of the EU's three biggest members - the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. Given that EU institutions tend to play the "bad cop," so that member states can assume the role of "good cop," the EU has become associated with disappointment for China.