India begins bumpy ride on Japanese train

Editor's note: On Thursday, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Japanese counterpart Shinzo Abe inaugurated India's first bullet train project, a $19 billion railway linking the western city of Ahmedabad and the country's financial hub of Mumbai. The joint venture is scheduled for completion by 2023. Four experts share their views on the "Indian Shinkansen" with China Daily's Cui Shoufeng. Excerpts:

Beijing, Tokyo are both New Delhi's partners

Japan's Shinkansen network has a global reputation for speed as well as safety. The Modi government has good reasons to base India's first high-speed train project on the Shinkansen network. Japan's favorable soft loan is also a boon. But India is not limiting its railway cooperation to Japan. It also has similar projects with China, from intercity trains to subways.

As for the high-speed rail project's economic prospects, along with great potential there are limitations. There has been a drop in the India-Japan trade volume of late. The ambitious Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor, touted as the world's largest infrastructure project in which Japan has a high stake, has been delayed. But both Modi and Abe appear determined and ambitious to deepen bilateral ties.

Surely, India sees Japan and China as two partners in terms of railway construction. The competition between the world's two high-speed rail pioneers, to some extent, could give India an advantage in railway construction.

More important to improve existing network

The 508-km high-speed train line, which is expected to cut travel time from eight hours to just over two hours, is not exactly what India needs. As a joint venture between Indian Railways and Japan's Shinkansen Technology, the project will use Japanese trains and technology, which in theory would allow the train to run at 350 kilometers an hour, more than double the maximum speed of the fastest Indian trains, and carry 750 passengers. But is India ready for its own "Shinkansen"?

Not quite so. The high-speed rail project was conceived over a decade ago, but picked up speed only three years ago, because the project was considered too expensive for India even if the top speed was limited to 250 km an hour. Hailing the project "as good as free of cost", Modi did not shy away from saying that it was only made possible with Japan's soft loan, which accounts for nearly 85 percent of the total cost with repayment spread over 50 years.

Despite Tokyo's generous offer, New Delhi cannot afford to import Shinkansen trains from Japan or keep the fare at the current level. India is right to overhaul its accident-prone colonial-era railway network and build the line along densely populated parts of the country, but the lack of experience in managing a high-speed railway and building bullet trains could hold its ambition back. Whether local commuters will be capable of paying for the more expensive ride is also questionable.

In comparison, expanding the existing rail network is a more profitable option for countries such as India. And to revamp its railways without burning subsidies to fuel the high-speed operation, New Delhi should build more train lines that allow both conventional trains and bullet trains to run at 160 km to 200 km an hour. China has the expertise and experience of running such moderate-speed, easy-to-manage trains. It is a pity that India, which often thinks China as an imaginary rival, has gone for a more costly option.

A political game full of the risk of failure

India has good reason to improve its railway system given its large, almost evenly distributed population and under-funded, poorly maintained railway network. To get rid of low capacity and prevent frequent accidents, the Modi government has proposed a "Diamond Quadrilateral" linking Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata with high-speed railways despite people arguing that revamping the old railway system would be more cost-effective and more beneficial to passengers.

Choosing Japan's Shinkansen trains and technology has a lot to do with New Delhi's strategic concerns and Tokyo's more than favorable soft loan. The foreseeable rise of Hindu nationalists has basically ruled out the possibility of employing Chinese high-speed expertise, competitive as it is. Nearly 80 percent of the total project cost will be loaned by Tokyo at a meager 0.1 percent interest rate, with repayment over 50 years, an offer New Delhi can hardly refuse.

Japan, on the other hand, seems set to explore the Indian market despite the money-losing prospect. The success of Japanese automaker Suzuki in transforming India's auto market and creating millions of jobs across the industry starting from the 1980s will not be easy to emulate, though. Indians' demand for motorcycles and small cars is a lot higher than it is for high-speed trains, whose survival largely depends on India's transport policy.

The profitability of the Ahmedabad-Mumbai high-speed line remains questionable. The ticket price could be 50 percent higher than existing higher-class train tickets, and the sophisticated domestic budget airlines provide a good alternative.

Japan and India have no historical beef, yet they have one thing in common: "vigilance" toward China's rise. Despite this, the high-speed train project carries little strategic implications for Beijing, which is in close cooperation with New Delhi in terms of subway systems and normal railway networks. The possible Japan-India infrastructure cooperation near the China-India border, however, is something worth noting.

There is hope that India's first high-speed train project, which covers regions that are among the country's wealthiest and most populous, would bear fruit. Struggling to carry through the 2013 Land Acquisition Act nationwide, Modi has managed to reduce the land acquisition barriers in some states with the high-speed rail proposal and increase his political support there. But the future promotion of high-speed trains would dealt a big blow should the project fail.

Real aim could be deeper strategic cooperation

Few would lay a bet on Japan's export of Shinkansen to India making profit. The real intention of Tokyo, which refrained from selling its bullet trains to overseas markets until 2004, is to crack open India's market for long-term gains.

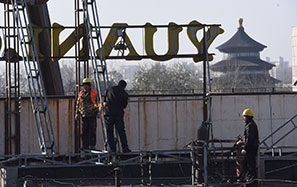

Reports suggest Tokyo's latest gift to New Delhi may be the E5 series Shinkansen bullet train, the fastest of its kind that went into commercial operation in March 2011. Manufactured by the consortium of Hitachi and Kawasaki Heavy Industries, the E5 trains apparently have strategic implications for Abe.

Kawasaki owns the technologies for building the Soryu-class submarine, which is one of the mightiest in the world and pursued by India. The high-speed rail deal, despite its unpromising economic prospect, could be part of a bigger plan to lure New Delhi into purchasing the submarines it desires.

Hitachi is based in Abe's ancestral hometown Yamaguchi prefecture, a constituency of his younger brother Nobuo Kishi, who, too, is also a leader of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party. Selling the bullet trains to India could bring tangible benefits to the company and thus would strengthen the political base of the Abe family.