Bringing life back to land of tea

Giri Kadurugamuwa climbs onto a mountain slope by the roadside and breaks off a big chunk from the exposed root of a tea tree. Within little apparent effort on his part, the chunk falls off like a piece of dried biscuit.

"It's very brittle," says Kadurugamuwa, director of the Alliance for Sustainable Landscapes Management, an NGO dedicated to promoting the sustenance of biodiversity in managed landscapes.

For the past two years the alliance and an international NGO that specializes in ecologically sensitive farming, Rainforest Alliance, have been working on a land protection project in tea growing areas of central Sri Lanka. The work is supported by the United Nations Environment Program with financial backing from the Global Environment Facility, an independent funding body with a global reach.

|

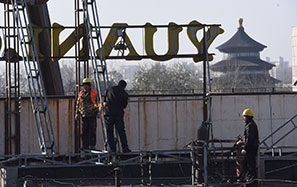

Tea pickers toil in the sun at Kahawatte Plantations in Ratnapura, in SriLanka's central highlands. |

They work with tea factories and estates, trying to reach smallholder farmers - tea growers with land of less than about 4 hectares. Big tea plantations in Sri Lanka can consist of 15 estates or more, each covering hundreds of hectares.

Knowledge is passed by providing training for trainers. Well-trained staff from big plantation companies are expected to teach the small holder farmers, whose produce later feeds the rollers in the factories that the companies own.

Janaka Gunawardene is the manager of a tea factory in Ratnapura, in the central highlands of Sri Lanka. The factory is part of a very big outfit, Kahawatte Plantations, which means it can always obtain leaves from its own vast area. However, the factory also buys a lot from small growers to keep its own production lines busy. (Because the small growers lack the means to process leaves, they are forced to sell the raw material to factories.)

"Our company is the very first regional plantation company to get the Rainforest Certificate for sustainable land use since the commencement of the project in early 2015," says Gunawardene. "Although there are other tea estates in the region that have got the certificate since then, ours is the only one that has included the small growers in the project."

A key aim of the training is to reduce the use of chemical pesticides and herbicides, one of the main causes of land degradation, which in turn leads to the brittleness of tree roots.

"A whole set of problems could arise and have already arisen with the over use of chemicals for the past 30 years," Kadurugamuwa says. "Chemicals, intended for harmful insects and weeds that may overgrow the tea trees or compete with them for nutrients, inevitably kill everything else, from the good insects to birds and small animals that feed on the insects and grasses. As a result, mites have multiplied, as the curled-up tree leaves clearly indicate.

"Meanwhile, losing its grass cover entirely to chemical herbicide, the land becomes exposed. And big rainfall can wash away many nutrients from the soil. Even worse, after a number of years, many bad insects and noxious weeds will have developed tolerance toward the chemicals, leaving farmers with little choice but to adopt even stronger ones."

Saman Kumara, a smallholder tea farmer, knows all about that. He notes that the animals, rabbits for example, are back after his farm drastically cut its use of chemicals over the past two years. "The rabbits can help us with the weeds. And even the millipedes are back. And when you have millipedes, you can tell for sure that the soil isn't that bad, since the insects cannot live in hardened soil."

These days on Kumara's farm the weeds are removed by hand. "We convert the grass and other reducible farm junk into fertilizers - a practice that helps us to keep costs down."

Better soil means higher-quality tea leaves and higher income. But a farmer must have the determination to weather the first one or two years, when the reduced use of chemicals causes an initial fall in tea production.

"I felt I had no choice because the tea garden, by the time I decided to turn to sustainable management, was already experiencing a production downturn due to land degradation," Kumara says.

Sri Lanka produces 338 million kilograms of tea a year, bringing in foreign exchange of $1.6 billion (1.5 billion euros; £1.3 billion). Ratnapura, the biggest tea-producing region, has nearly 98,000 tea smallholders who together own about 30,000 hectares of land.

About 30,000 smallholder farmers are being trained in sustainable land management practices, which will then be applied to at least 60,000 hectares of team farms and plantations, the UN says.

The project is being replicated in other tea-producing countries, including India, Vietnam and China.

Hu Xinyan, coordinator of the program in China, says this emphasis on smallholder farmers is of profound significance for her country, where farmland has been divided up and rented to individual growers for decades.

"In China, we don't have those big plantations that you'll find in India or Sri Lanka. Instead, we have vast numbers of small growers, each with land measuring somewhere between 10 mu and 30 mu (between 0.67 hectares and 2 hectares). We reach them through the region's leading tea companies, because they are the buyers of tea leaves and therefore have a big say when it comes to green farming.

"We are also working closely with local government officials responsible for developing the tea industry. Faced with tough competition and land degradation, they have taken part in our training for trainers scheme."

Hu stressed that zero use of chemical pesticides and herbicides is not a prerequisite for a grower to be granted the Rainforest Alliance certificate.

"The reduction of chemicals is bound to a step-by-step process, a process we try to trigger with an encouraging attitude. So we give the certificate to any grower who can prove that efforts have been made and that the use of chemicals has been reduced several years in a row. On rare occasions, the use of chemicals may increase in a certain year. We will not withdraw our certificate if the grower can demonstrate that there is a very special reason for doing so - extreme weather or a plague, for example."

But then there is the issue of labor costs. To do without chemicals means that many things, such as removing noxious weeds, must be done by hand or at least by people operating portable mechanical grass removers.

Dulshanka Jayathilaka, manager of Bearwell Estate, says labor costs have rocketed in the past few years. His estate was certified by Rainforest Alliance before the UN project started.

"More than 3,300 people live on the estate, which covers 307 hectares, but only 17 percent of them work for us. The rest are the workers' families."

However, he acknowledges that the Sri Lankan government subsidizes the land, which means the private company has paid less for it than it otherwise would have. In turn, it is expected to take a degree of social responsibility by providing land on which even those who do not work for the estate can live.

Improving tea garden employees' working conditions and lives in general is among the UN project's goals.

"Reducing the use of chemicals obviously benefits the tea garden workers, but we need to do more, and we need to have a whole different mechanism, a whole different mindset and even consumer habits for any change to be sustainable," Hu says.

"We have a long way to go."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn