Out Of The Shadows

|

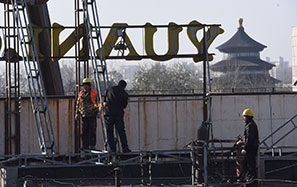

The main hall is the only structure that remains from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). The temple also features four ancillary halls as well as a bell and drum tower and several side rooms. Photos By Feng Yong Bin /China Daily |

Beams Of Light Reveal Astonishing Detail In Masterfully Crafted Frescoes In A Buddhist Temple

In 1933 the German photographer Hedda Morrison went to a western suburb of Beijing, where she discovered what she would call the city's most interesting temple. With a Rolleiflex twin lens camera and a heart captivated by the beauty of oriental art, she recorded in black and white the stunning frescoes on the walls of the temple's main hall.

However, the way Morrison went about her work, which she wrote about in detail, is likely to fascinate the modern reader almost as much as her pictures. Since the frescoes remained in the shadows, she had to remove some of the roof tiles to allow in sufficient light. A photographer with her tried to blow magnesia powder onto blazing paraldehyde to illuminate what can only be called a darkroom. But those efforts went unrewarded, filming being abandoned when Morrison was accidentally burned.

However, the flash that had lit up both the hall and Morrison's mind refused to be dimmed. For me it was reignited one morning early last month as the lady who was my guide led me into the ancient hall and switched on a flashlight.

It was a miracle moment, when the photographer's experiences, which I read about years ago, jumped out from the back of my mind, vivid and fresh. I was her, beholder of a visual wonder revealing itself. As the beam of yellowish light swept across the wall, patches of fresco emerged one by one from the pitch black darkness to charm me with warm hues and myriad images, before retreating back into the shadows to resume their silent, self-effacing existence. It was like being tantalized by a siren call, the frescoes under dim, wandering light seeming to call for attention but at the same time wanting to be left alone.

"The mental impact of Morrison's experiences must have been enhanced by the decision to allow absolutely no light into the main hall," said Lu Shaojie, my guide, pointing to the heavy curtain on the windows. "It's aimed at protecting the frescoes, with the inadvertent effect of accentuating their beauty, for which few people are truly prepared."

And few, according to Lu, have dug deep into the history of the frescoes, and by extension that of the temple. Built between 1439 and 1443, Fahai Temple was commissioned and funded by Li Tong, a powerful eunuch of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) who is believed to have served five successive emperors. According to the historical records, Li built the temple to express his gratitude for royal favor. And to create the murals, artists were recruited from all over China and worked under the supervision of the most celebrated court painters of the day, among whom 15 had their names inscribed in a stele placed inside the temple.

The result of the five-year endeavor is a grand temple built on three terraces and scaling Cuiwei Mountain. The original design featured a main hall and four ancillary halls as well as a bell and drum tower and several side rooms. Today the main hall is the only building that has survived the ages, the others being reproductions. And the frescoes inside are the sole reminder of the length all those involved went to in creating this ultimate tribute to Buddha, and to the Ming emperors who were among the Buddha's most powerful worldly followers.

Covering 237 square meters in total, the frescoes include 77 figures - not including animals - in nine scenes that amount to either individual or group portraits. The tallest one is 2 meters high and the shortest 50 centimeters high.

A detail Lu never fails to point out to visitors is the white gauze draped across the body of Avalokitesvara, or Bodhisattva, the Goddess of Infinite Compassion, painted on the back wall of the altar. This flimsy, barely-there piece of clothing is made up of little hexagonal flowers, each petal measuring less than one square of a centimeter, composed of eight veins.

"The brush used for this purpose must have no more than three hairs," says Lu, referring to the fluidity and cloudiness of the fabric that would be lost if viewed up close. "Believe it or not, such meticulousness can only be fully appreciated when the viewer is looking at the subject from a distance.

"Thanks to the great virtuosity of the artists, the Fahai frescoes have a suggestion of three-dimensional realism untypical of traditional Chinese painting."

However, the status that the murals enjoy today in Chinese art history has not prevented them from vicissitudes, especially in modern times. By the late 19th century the temple compound had been reduced to an ad hoc refugee camp, colonized by paupers and tramps. The temple, once a popular site of pilgrimage, gradually fell into disrepair, a state in which it remained during the tumult in the country in the first half of the 20th century, until the spring 1950, the year following the founding of the People's Republic of China.

Tao Jun is the vice-director of the Fahai Cultural Relics Protection Bureau, the organization directly in charge of the temple's protection and maintenance, with its office on the temple precincts.

"In the spring of 1950, some artists who had heard about Fahai went there to paint en plein air," Tao says. "There they discovered, to their great horror, iron nails driven into the walls of frescoes. It turned out that soldiers stationed there had used the nails as clothes hangers."

The alarming message was soon passed to Ye Qianyu (1907-1995), a renowned painter and art educator who at the time taught at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. It did not take long before it reached other important cultural figures, and ultimately, the Beijing municipal government, which alerted the army.

"Any further damage by unmindful soldiers was stopped," Tao says. "Fearing that pulling out the nails might cause more destruction to the wall, they were allowed to stay."

They are still there on a lower section of the northern wall in the main hall, together with a couple of holes that used to hold the nails.

"As jarring as they may seem, these holes made possible the study of the wall's composition," says Tao, who attributes the survival of the murals to the walls' stability and to fate.

"Many Western murals painted around the same time suffered serious cracking and bulging, but this has rarely happened to the Fahai frescoes."

A closer inspection of the hole reveals a thread-like fiber structure. As thin as hair but much shorter, the material is mingled with mud and plaster to form the wall.

"In rural China it was common to mix straw and cornstalk with mud to build houses," Tao says. "The stalks acted as the bone of the wall, giving it support through what is known as its tensile strength. For the construction of the Fahai wall, mud was blended not with straw, but with goat's hair, which has much greater tensile strength. Egg white might also be added to provide adhesiveness to the mix."

The goat's hair and egg white may have reduced the wall's vulnerability in the hands of nature, but it needed a courageous soul to save the frescoes from those determined to have them destroyed.

The last time Ding Chuantao, 82, visited Fahai Temple was in 2010. But between 1966 and 1981 the Chinese language teacher at Beijing No. 9 Middle School lived in the temple grounds.

"The temple served as a dormitory for the school's male students from 1952," he says. Then in 1967 the cultural revolution (1966-1976), a political movement that had among its stated goals the crushing of everything considered feudal, began. Classes were soon ended as all students were gone. The temple became extremely peaceful, and it was a peacefulness that suited me well. I soon moved from my original housing down the mountain into one of the temple's side rooms."

That was the genesis of the friendship between Ding and Wu Xiaolu, the doorman of the middle school whom many today consider the protector of the Fahai Temple.

"On one occasion a handful of teenage boys aroused by the movement rushed into the temple wanting to smash everything up," Ding says. "Realizing that the frescoes were more important artistically than the wooden Buddha sculptures that lined the frescoes' lower part, Wu made a painful yet quick decision. He said to the boys, 'Smash the sculptures if you want, but don't even try to put your hands on the frescoes before you smash me up.'"

The boys balked and the murals were saved. And according to Lu, the darkness inside the main hall also helped, since the vandals did not realize how sumptuous the frescoes were. She points out for me a horizontal line that goes through the 11-meter-long frescoes on both the eastern and western walls. It is about 60 centimeters from the bottom of the painting.

"The part above that line has been exposed for 600 years, while the part below it has just done so for 50 years, since when the Buddha sculptures right in front of the walls were destroyed on that fateful day," she said.

Today, those sculptures can only be viewed in the black-and-white pictures taken by British reporter Angela Latham, Morrison's contemporary who photographed the temple in 1937 and had the pictures published in the Illustrated London News that same year.

Wu, in the final years of his life, suffered from Alzheimer's disease and handed the keys to Fahai's main hall to Ding. He died in the mid 1970s aged 74. "He never left the temple," Ding says.

Before his death, Wu, who had been an antiques dealer for years before a series of misfortunes brought him to Fahai, left a will in which he requested to be buried near the temple. The family obliged.

Lu saw the murals for the first time in 2011, before deciding that she "wanted to do something for them". Today her faith is tightly bound to these murals.

"There were two big earthquakes in Beijing, in 1679 and 1730. Fahai Temple was shaken, but the murals remained intact. It's true that time has done its worst. And at times in Fahai's history the lack of maintenance has resulted in roof leaks and cracks in the murals. Yet if you examine the paintings inch by inch, as I have, you will see that never, not even once, has a major crack or rain mark passed across the face of a Buddha."

Lu, 55, believes that the frescoes' ultimate greatness resides in their power to move.

"Step back and look into the eyes of the Bodhisattva, then walk slowly from her left side to right," she says, gesturing to me. So I do. And the goddess, looking down with her willow leaf-shaped eyes, never takes her silent gaze off me. Put another way, where I go, her eyes go.

"See what happens?" Lu muses. "She's with anyone who's with her."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn