Supply-side up

Latest buzzword has caught the world's attention, but it is different from Reaganomics or Thatcherism

One of the most current fashionable terms in China - now even repeated by ordinary people on the street - is supply-side reform.

It was certainly a high priority in the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-20), published on March 17, which will set the course of government policy up to the end of the decade.

The government's adoption of a concept associated in the 1980s with the free market economics of both US President Ronald Reagan, dubbed Reaganomics, and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, has attracted worldwide attention including from The Economist and The New York Times.

The term supply-side, or gongji ce, was first used by President Xi Jinping in keynote speeches at the end of last year.

At the recent two sessions of the National People's Congress, the country's top lawmaking body, and the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, the top political advisory body, some of the policy detail was fleshed out.

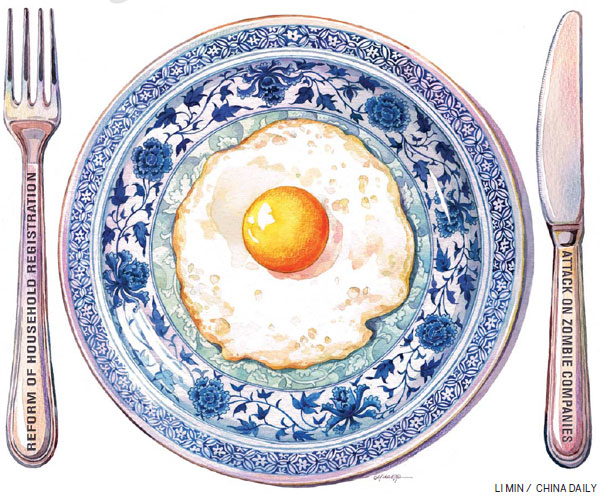

A central plank of China's supply-side economic program will be reform of China's 150,000 state-owned enterprises and, in particular, getting rid of so-called zombie corporations, the worst performing of all.

One of the problems of the Chinese economy is that too many labor and capital resources are tied-up in these enterprises, which are often in key strategic industries.

Since the turn of the century they have been growing at a third of the rate of the private sector, which now boasts world-beating companies such as telecommunications group Huawei and technology giants Alibaba and Tencent.

According to Gavekal Dragonomics, a Beijing-based economic research company, SOEs had a return on assets in 2014 of 4.6 percent, barely more than half that of the 9.1 percent of the private sector.

Their performance is, in effect, a drag on the economy's ability to supply goods and services.

Another major area of supply-side modernization will be reform of hukou, the household registration system.

The government wants to make it easier for migrant workers to move with their families to cities and lead more stable lives in urban areas.

This, over the longer term, will lead to greater flexibility of the labor market, resulting in many workers being in better-paid employment with the effect of also boosting consumption.

Another aim of the government is to promote innovation through a variety of initiatives, to upgrade the economy so that the goods and services supplied will be the ones demanded by an increasingly affluent middle-class society.

Taken together, these supply-side reforms should, according to the government, achieve the shift the economy needs to make from an export and low-cost manufacturing driven economy to one more built on services and consumption.

Xu Bin, a professor of economics and finance at China Europe International Business School in Shanghai, believes adopting a supply-side approach is the only viable option now available.

"This is a critical point for Chinese policy overall. We have seen the export sector experiencing negative growth (exports fell 25 percent year-on-year in February), manufacturing is very bad right now and investment has reached a bottleneck.

"The only solution for China over the next five to 10 years is to adopt supply-side reform."

Xu adds that there is nothing necessarily mysterious or complex about the concept of such reforms.

"The key word really is efficiency. You want to do whatever is likely to increase the efficiency of the production process. It can include a lot of areas, including innovation and technological progress, higher-quality management and increased levels of education, which improves the productivity of the workforce."

One of the criticisms of the current debate in China has been that supply-side has been deployed as a catch-all term to describe a whole series of otherwise disjointed policies.

Zhu Ning, vice-dean of the Shanghai Advanced Institute of Finance, believes there is definitely a risk of this.

"I am losing track slightly. If you take a step back, many of these proposed policy reforms such as of SOEs and the labor market have been brought up much earlier without having the label of supply-side attached," he says.

The use of the term supply-side has brought up the parallels with the Reaganomics of the 1980s, which along with Thatcherism in the UK, fundamentally altered the course of post-war economic policy in the West.

Out went the Keynesian policies that had largely consisted of fiscal policy to control the level of aggregate demand in the economy with the aim of maintaining full employment but had resulted in stagflation (low growth and inflation) and in came free market policies embracing Chicago school monetarism that had originated in the 1950s but had become particularly vocal in the 1970s.

Key elements of this in the US were tax cuts and deregulation, and a landmark event was Reagan's 1981 Budget when he reduced the marginal tax rate for high earners from 70 to 50 percent.

Paul Craig Roberts, who was assistant secretary to the US Treasury at the time and who has given an address to Chinese leaders on supply-side economics in Beijing, believes there are parallels between what happened in the US then and the challenges facing China now.

"Supply-side economics entered the scene (in the US), because the Keynesian policymakers had no answer to the worsening tradeoffs between inflation and unemployment," he says.

"In short, to combat inflation within the demand management model was requiring higher rates of unemployment, and to boost employment was requiring higher rates of inflation."

Roberts, author of The Supply Side Revolution: An Insider's Account of Policymaking in Washington and who has had his books translated into Chinese, says what China is trying to deal with is not stagflation but high debt.

He says leading Chinese thinkers in this area such as Jia Kang, president of the China Academy of New Supply-side Economics, the leading think tank, realize they have to change the economic model, which has relied on boosting consumption and investment with cheap money.

"In other words, an extraordinary amount of income is diverted away from the demand for goods and services and from real business investment (as opposed to investment in financial instruments). The financial empires built by debt finance are draining the Chinese economy of the ability to grow," he says.

Foreign multinationals in China have welcomed China's supply reforms because they believe an upgrading of the economy will benefit their businesses.

Gaby-Luise Wuest, managing director of Infiniti China, the luxury division of Japanese carmaker Nissan, believes it will be good for the premium car market in the longer term.

"Supply-side reform requires companies to focus more on innovation, and therefore provide opportunities for innovative manufacturers," she says.

Zhang Ying, managing director for Greater China for Dassault Systemes, the French multinational software company, thinks such an approach will drive the development of technologies such as cloud computing, big data, the Internet of Things and 3-D printing.

"As far as I am concerned, supply-side structural reform will leverage all effective ways to improve business processes, ranging from research and development to sales and marketing."

Huang Chenhong, president at Dell Greater China, believes that if supply-side reforms are successful, it will create a better business environment in which to operate.

"Supply-side reform, which encourages tax cuts, entrepreneurship and deregulation, will increase technological revolution and high-quality goods and services," he says.

Zhu, author of the recently published China's Guaranteed Bubble, which looks at some of the risks within the Chinese economy, believes China's weakness is not on the supply-side but on the demand-side of the economy, and that is what the government should deal with.

"The problem in China is that we don't have enough consumption, and that is what we should focus on," he says.

He says the problem in both the US and the UK 30 years ago was different from what it is in China today.

"In both cases the demand side was strong enough but there wasn't enough incentive for companies to produce what the demand side desired. Household consumption made up about two-thirds of economic growth in both the UK and the US. If supply lagged behind demand you had a continual risk of inflation."

Xu at CEIBS, however, insists that China is not blindly following some old model of supply-side reform, and it is also aware of some of the failings of Reaganomics and Thatcherism that eventually led to increasing income inequality.

"I think they want to learn from the Western supply-side policies and generate some spirit of increasing efficiency by freeing the private sector, but not to the degree that is going to negatively effect the working class," he says.

"China wants to raise efficiency while actually reducing the income inequality gap."

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn