Mad about cow

Beef is the word at some of the trendiest restaurants in Shanghai, where Chaoshan cuisine finds expression at hotpot eateries all over town, Xu Junqian reports.

While the bull disappeared from Shanghai's roiling stock market in the latter half of 2015, it has been easy to find in-between the chopsticks of the city's most active diners. In fact, beef may have surpassed pork for choice by many in recent months.

Beef lovers have long gathered at upscale Western steakhouses and Taiwan-style beef-soup noodle eateries. The trend-setting, however, is most apparent at a less high-profile venue: The Cow's Story, featuring a rather niche cuisine from Chaoshan, a region that many may only know vaguely as "somewhere in southern China".

"Chaoshan beef preparation would not be overshadowed when compared with Japanese Wagyu or any fine fillet from steakhouses," says Chen Manqi, a native of Chaoshan, Guangdong province, who now lives and works in Shanghai.

For sure, the 31-year-old is biased, as she has been running several restaurants serving the cuisine from her hometown for more than a decade in Shanghai.

But you don't have to take her word for it: Chaoshan hotpot restaurants are sprouting up around Shanghai, with more than 200 recent openings in less than a year. For context: The total number of hotpot restaurants in the city is around 6,000, according to figures from Dianping.com, the most-used restaurant listing in China.

Chen was among the first in the city to open a Chaoshan hotpot restaurant, back in April last year, but she says it has been amazing, even to a fan like herself, to see so many similar ones mushrooming during the past year.

Chaoshan hotpot, or Chaoshan beef hotpot, distinguishes itself from relatives like the spicy Sichan version or the pricey Hong Kong style by concentrating very much, if not entirely, on beef.

In fact, people there have been so serious about the meat, which is dipped in the broth for no more than one minute, that a completely new terminology has been coined to name the variety of cuts from different parts of cattle.

Diaolong, for example, is the equivalent of rib-eye; shibing refers to the finest cut of chuck that accounts for less than 1 percent of a whole cow. There are altogether seven to eight types of cuts named and offered at a Chaoshan hotpot restaurant.

There is also a strict set of rules about how many seconds each cut should be dipped in the boiling broth, which contains nothing but water and chopped celery. (At some restaurants the broth would be beef bone stewed for hours before being served.)

"Chaoshan cuisine is very much about originality and freshness," says Chen, who started cooking and selling Chaoshan dishes in Shanghai with her husband as street vendors, mostly to Guangdong natives who were doing contract business here. The cooking style is also known as Teochew cuisine, Chiuchow cuisine and Chaozhou cuisine, and it has influenced (and been influenced by) both Cantonese and Fujian cuisines, which originated nearby. Chen says Chaoshan cuisine is less delicate than Cantonese and puts more emphasis on the ingredients used.

For the beef hotpot, only meat from female yellow cattle that are 1 to 3 years old is used, which is considered to be tenderer than its male counterpart but still features good fiber and firmness.

After meat arrives in large chunks at Chen's restaurant, usually within four to six hours of slaughter, veteran butchers slice it paper-thin, without disrupting the fiber of the meat.

"It's a job only those from Chaoshan can accomplish and excel at," boasts Chen.

Yan Tao, chief editor of China's Southern Metropolis newspaper, wrote in his column that people in Chaoshan "borrowed" the beef-eating tradition while doing business with their neighbors, Hakka people, a traditionally mountain-dwelling group who rely heavily on cattle for transportation and food.

The fact that Chaoshan doesn't raise its own cattle makes the people there particularly treasure the animal, and they make use of every bit of it. For example, the back shank, which is mostly discarded in other cuisines for being too stringy, is used for meat balls in Chaoshan, with methods the coastal region has developed for making fish balls.

To highlight the flavors of the beef, a trio of sauces is offered to suit different palates. Satay sauce has been "transplanted" by Chaoshan businesspeople after traveling back from its birthplace in Southeast Asia. Its slightly sweet flavor is loved by many, but sometimes overshadows the subtle sweetness of the beef itself. The distinctive aroma from the garlic oil matches particularly well with lean meat, for those not troubled by the after-smell of garlic. Puning yellow-bean sauce, which has been as prevalent in Chaoshan as spicy sauce is in Sichuan, offers an exciting wake-up experience to the tongue with its strong but fragrant saltiness.

To conclude the meal in Chaoshan style, order a plate of guotiao, or rice noodles, and throw them in the broth for three to five minutes. The result is a mouthful of slippery and smooth noodles, each thread redolent with the flavor of beef.

By then you may be wishing we humans could have as many stomachs as cattle do.

Contact the writer at xujunqian@chinadaily.com.cn

|

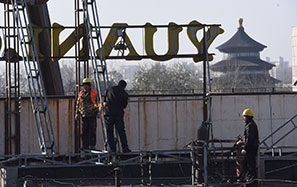

Chaoshan beef hotpot restaurants become popular in Shanghai because of the strict selection of beef and cutting rules. Photos By Gao Erqiang / China Daily |