The artistic power and glory of qianlong

As he held sway over the land, he devoted his life to one of his key roles: Guardian of the country's art ZHAO XU

For art lovers the story is familiar enough: Master painter is found dead, paintbrush in hand. After all, to work until one's last breath is a natural choice for someone who has given one's life in the service of his muse.

But the special thing about this artist, who painted on the first day of the Chinese lunar new year in 1799, two days before he died, is that he was an emperor, indeed the longest-reigning emperor in Chinese history.

"In fact Hongli was continuing a tradition where an emperor would paint auspicious motifs to usher in the new year," says Yang Danxia, a senior researcher of traditional Chinese painting and calligraphy at the Palace Museum in Beijing.

"This particular one painting had joined the more than 1,000 others to form his portfolio."

In addition to those, Yang says, are nearly 10,000 works of calligraphy, not to mention the emperors' countless epigraphic writings that adorned his surroundings. "In terms of quantity, he is peerless," says Yang, who attributes the wonder that was Hongli to an education that could only be called classic.

"For nearly two decades before Hongli ascended the throne, when he was 25, he was under the tutelage of literary masters. Belonging to a millennium-old tradition that treats literary cultivation - and by extension calligraphy and painting - as one's major pursuits, these masters nurtured in the young man a passion that would endure for the rest of his life."

However, behind everything that happened to the future emperor there lay a single purpose, the necessity to rule, says Wang Yimin, Yang's colleague at the Palace Museum, a specialist in ancient Chinese calligraphy.

"Hongli, the sixth emperor of the Qing Dynasty (1636-1912), descended from a lineage of Manchu rulers who had come from the north to conquer the whole of China, the majority of whose population was Han Chinese.

"Successive Manchu emperors, stigmatized by what they felt was their lack of cultural sophistication, went to great lengths to ensure their offspring would be raised in the most classic of the Han literary tradition.

"To submerge themselves in this tradition was to be able to communicate with society's elite and thus to gain legitimacy to rule. A vital part of that tradition is visual."

So it was with gusto that the emperor, better known by his regnal title Qianlong, meaning enduring eminence, took up painting. Some of his works were given to his favorites at court, as a token of benevolence, and no doubt as a subtle hint of his artistic prowess.

Yet Tian Yimin, another expert on ancient Chinese painting and calligraphy at the Palace Museum, believes that the emperor, despite his immense hubris, was well aware of his limitations, or, put more bluntly, he knew he was no genius.

"His paintings are consistently of the second order," Tian says. "So, while doing his own art he turned to collecting so that his name would be more intimately linked with the country's lustrous artistic tradition."

There was nothing genteel or understated about the way in which he went about that task, and today many art purists shake their heads in dismay as they survey the results.

"You'll find his stamps and inscriptions on many of the masterpieces that comprised his huge collection," Tian says. "There are so many of these things, done at various times, that in some cases they overshadow the artwork itself."

For Qianlong, these marks were regal seals that proclaimed him head curator of China's art; beyond that though they were messages on a more intimate and personal level.

"Qianlong made it a practice to record his thoughts on the extended fringe of the paintings," Tian says. "You get the feeling that he was trying to communicate spiritually with those whose artistic genius he aspired to."

Masterpieces

He spared no effort to bring the masterpieces within the confines of the Forbidden City, the royal abode for successive Qing emperors. It is now the Palace Museum, and it is there that Tian and her colleagues toil away year in and year out sorting through the vast royal collections.

"To get all of these works, a huge amount of coaxing, if not coercion and outright confiscation, must have gone on," Tian says. "And the emperor would presumably have used middlemen whose activities would not have been mentioned in official records."

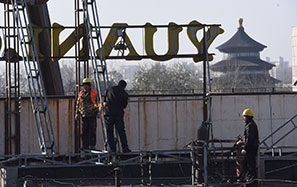

The cream of the collection later formed his imperial painting catalogue Shiqu baoji. The museum staged a grand exhibition under that title from September until early last month that featured a total of nearly 300 paintings and works of calligraphy, all drawn from the catalogue.

For Qianlong, the custodianship of the world's most fabulous art collection carried a special responsibility: he was expected to be able to differentiate between the masterpieces in his possession and their numerous copies and fakes. To help in that task he had a coterie of art experts as advisers, but in these issues he was keen on having a say in the matter.

These judgments, unlike those he made on court affairs, were not necessarily the final say on the matter, and sometimes he overruled his own decisions.

"When it came to the authenticity and provenance of an ancient masterpiece, Qianlong was a tireless seeker of the truth," says Zhang Zhen, a researcher of Chinese painting and calligraphy at the Palace Museum.

"There were cases where he deemed a much-treasured piece to be authentic, only to have it discredited some decades later, when a similar and better-painted one turned up. And if there was debate, the emperor would get hold of both versions, so that there would be no misgivings later."

Tradition

Among all the Chinese painting and calligraphy masters, Dong Qichang (1555-1636) was the one the emperor valued above all, says Wang.

"Dong championed and enunciated theories on literati painting, casting well-educated scholars - as opposed to professional painters - as the right heirs of China's centuries' old painting tradition. For Qianlong, a passionate poet and essayist who always sought to couple military might with literary achievement, this had a clear appeal. Most importantly, Dong died just before the fall of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and the founding of Qing by the Manchus, so it could not be said of him that he had served an enemy regime."

So Dong was a figure who united rather than divided, and in the world of Qianlong, art was never far from politics. This politicization of art inevitably led to what Tian calls "an ossifying of the art evaluation system".

"In line with Qianlong's taste for the grandiose, art under him tended towards the delicate and decorative, leaving behind a more elegant, simple style that characterized the reign of his father, Emperor Yongzheng.

Yet Qianlong, not unlike his grandfather, the open-minded Emperor Kangxi, also drew on the services of foreign missionary artists who had adopted the three-point perspective in painting.

"What Qianlong did was to let the foreign artist paint the face - as in one of his own portraitures - while allowing the Chinese painters to finish the rest of the work, including the folded clothing and the scenery beyond," Tian says. "Qianlong appreciated a pinch of realism, without letting it undermine that soothing, poetic mood of Chinese painting."

Art and politics

Yang says that one man Qianlong particularly admired and sought to emulate - with his collection, if not his own paintings - was Zhao Ji (1082-1135). Known as Emperor Huizong, Zhao reigned for 25 years during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). A master painter and calligrapher with unmistakable personal style, Huizong was canonized in Chinese art history. If Qianlong was no artistic genius, Huizong was an absolute dunce as a ruler. Having been captured by invaders from the north, he suffered humiliation for nearly 10 years and eventually died in enemy territory when he was 53. His captors were the Nvzhen People, a nomadic group remotely related to the Manchus.

"Despite falling completely for Huizong as a born artist, Qianlong was ever mindful not to repeat his political disasters," Yang says. "Consequently, he made a deliberate effort to incorporate his artistic pursuits into his broader vision of governance."

Governing tool

One example is the Painting of Five Bulls from the Tang Dynasty (618-907), arguably one of China's 10 best historic paintings. Having designated a special building in the Forbidden City to house it, Qianlong treated the work more as a piece of religious iconography than a mere art treasure, Zhang says.

"He paid ritualistic visits to the painting every spring, when he conducted a farming ceremony to pray for a fertile new year. He did this without fail for 23 years."

Yang attributes Qianlong's unique role in Chinese art history to several things.

"He became emperor in 1736, exactly 100 years after the Qing Dynasty was founded. And it took all of a century for the chaos of the dynasty-changing wars to subside. Also, when the Ming Dynasty fell, all the precious art works of the royal collection were dispersed. For the next 100 years they kept changing hands, until they ended up with Emperor Qianlong."

The emperor's abiding interest in art was aided by his age as well as his wealth, Wang said. "Ascending to the throne early in life may have stunted his artistic growth - after all, no one is going to dare criticize an emperor - yet it gave Qianlong an easy confidence that befitted his role as his empire's foremost art patron and collector."

After him, the fortunes of Qing took a decided downturn. Invaders eventually came from the other side of the ocean. One hundred and twelve years after his death, the empire was replaced by a Republic. China was never the same, and the walls of the Forbidden City proved to be much less impregnable than the powerful leader had believed.

Elusive painting

In hindsight, too, the emperor had other reasons for regret, Wang said.

"Qianlong always craved for a long scroll titled A Trip Up the River at Qingming Festival," he says, referring to the Song Dynasty painting depicting a bustling riverside scene during one of China's festivals. When it was put on view at the Shiqu baoji show this year, 170,000 people viewed the painting, some waiting in line for six hours for little more than a scant glimpse.

"Throughout his life, Qianlong searched high and low for that legendary painting, but to no avail," Wang said.

"Months after he died, his son and successor, Emperor Jiaqing, prosecuted a favorite official of his father held to be corrupt. His assets were confiscated, and there it was, the famous painting that was still at the top of Qianlong's wish list the day he died."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Emperor Qianlong(1711-1799) |