Keeping children out of harm's way

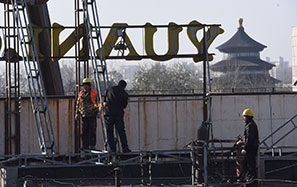

I am dedicating this column to Yuan Hai. Name not familiar to you? Yuan was 17 and one of the first firefighters who died at the Tianjin blasts last week. He was also the youngest to die. We'll never know quite what happened that night, but I think of him as a very brave boy.

Which is exactly my point. What was a boy of 17 doing in the front line of a chemical explosion? There are numerous questions to be asked about the tragedy, and Premier Li Keqiang among others seems determined to get answers.

Children have always been exploited, but we can put laws in place to stop proper institutions from doing so.

In Britain until very recently the army used "child soldiers" because it allows boys and girls to enlist at 16. After much international pressure, the country came up with a compromise. You can still become a soldier at 16, but you can't be deployed to a war zone till you are 18.

Nations lay down at what age a person can be charged with a crime, or at what age they can marry. Children don't have the vote, they have to wait for adulthood for that privilege.

Countries everywhere shape their own definitions of childhood.

Yet we continue to put children in the path of grave danger because for some reason it's deemed OK if they are defending their country or protecting their community.

I've never felt like that, for the most selfish of reasons. I don't want children making split-second decisions that could mean life or death. I want someone with experience, maturity and expertise doing that.

Better still, in the case of terrible explosions such as the ones in Tianjin, I'd prefer robots doing the job.

Many years ago I had a friend who was a senior fire officer in my home county. He pioneered the use of robots to investigate fires in the Channel Tunnel, which joins England and France under the sea. His logic was simple: Why endanger lives in a 40-km tunnel, when a robot can do the job better?

In China, of all places, which is way ahead of the game in the manufacture of robotics, firefighting seems an obvious application of known technology.

But robots aside, and getting back to the age issue. When life was very short, children did marry, go to war, rule countries. Now, so many people are living much longer lives, perhaps it's time to rethink and extend childhood.

As I'm writing this, the death toll from Tianjin is 114, one of whom is 17-year-old Yuan Hai.

Is it too much to ask that China could pass legislation keeping children out of harm's way in the name of protecting others? It would be a perfect memorial, to make him the last Chinese child to die in such circumstances, just following orders.

Contact the writer at susansimpson@chinadaily.com.cn