Expertise and ignorance in the fight against Ebola

Chinese experts who traveled to Africa to help countries affected by the virus faced tough conditions, but they found the experience unforgettable

|

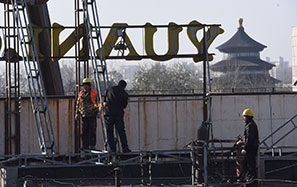

Zhang Liubo prepares medicine in Freetown, capital of Sierra Leone. Provided to China Daily |

Zhang Liubo says he was shocked to see people outdoors when he first arrived as part of the Chinese medical team to fight the highly contagious and deadly Ebola virus in Sierra Leone.

"Back in 2003, when China was in the throes of the SARS epidemic, the streets of Beijing became a no-go zone. People accepted and embraced their self-imposed confinement at home, out of fear," says the 52-year-old, who was sent to Africa by the Disease Control and Prevention Center to fight Ebola late last year.

"But there, at Freetown, the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone, as we were driven to the hotel at the end of a day's work, the locals were singing and dancing by the roadside, under a canopy of stars.

"They seemed to have a naturally optimistic streak. But there was also the ignorance factor to consider," says Zhang, who has recently completed his two-month stint as a disinfection and sanitation expert.

Sense of resignation

Whatever the reason, the local people's apparent calm and what appeared to be resignation shook Zhang to his core.

"A colleague from our team told me a story: A man who had displayed strong Ebola symptoms turned up at the door of a local hospital. A doctor came out, and asked the man to wait outside, under a big tree," Zhang says.

"So he waited, and waited, for the ambulance to take him to a designated place for Ebola patients, but death arrived at dawn, before the doctors, and found the man lying against the tree, still waiting ..."

Designated by the World Health Organization as "an international public health emergency", the disease was on its upswing when Zhang and his colleagues arrived in the middle of September. The 62-member team divided into two parts - the medical staff, who stayed inside the permanent or makeshift hospitals and dealt directly with suspected and confirmed Ebola victims, and the laboratory staff who operated the first mobile medical laboratory China has sent overseas. As an expert on disinfectants and sterilization techniques, Zhang was responsible for the sanitary conditions in the lab and, therefore, the safety of the staff. He spent two months breathing the chlorine-infused, sometimes unbearable, air while fighting his rising blood pressure.

"In a country that has only 200 doctors and 2,000 nurses, the death rate for local medical workers who'd been in direct contact with Ebola patients was about 20 percent when we arrived. Alarmed by the situation, WHO recommended the chlorine liquid for used sterilization work should be made to a concentration of 5,000 milligrams of active chlorine per liter of water," Zhang says.

"But after sticking to that standard for about two weeks, I discovered traces of corrosion on the metallic surfaces of the laboratory, for example, the doorknobs, which made it harder for the airtight door to close completely.

"In our efforts to eradicate any potential health risks, we had inadvertently opened a tiny window for the virus. After careful deliberation, we reduced the concentration drastically to 2,000 mg per liter, convinced that that amount would suffice. So far, we have been proved correct."

Long hours, tough work

The reduction in the level of chlorine produced a more tolerable environment for the staff who tested blood samples from patients suspected of having Ebola, and who sometimes worked nonstop for six hours at a time.

"When you think of our lab, don't think of any operating room you might have visited in a hospital. Instead, think of a sealed box where you can only enter if every inch of skin is concealed, and where, between entering and exiting, you are only allowed to do one thing - work," says Zhang. "No toilet breaks, no eating, or leaving in the middle of a shift - that's why the usual recommended time for anyone to work in such a lab is two hours, or four at maximum."

However, the overwhelming demand for tests soon rendered the time recommendation redundant. "We had planned to do 20 cases per day, but in reality, the number soon rose to 50 and then 60. For a few days in mid-October, when the infection was at its peak, the number reached 100," he says.

About 50 percent of all the samples tested positive. "The tests for the Ebola virus in blood are absolutely crucial because the deadly disease resembles typhoid fever or malaria in its early stages and could be wrongly diagnosed as such. That can cost patients precious treatment time and, therefore, their only chance of survival. A severe lack of medical resources in many hospitals meant that suspected Ebola patients were often placed together in one, or maybe two, isolation wards. This created an immense risk for all of them, and the lab results were badly needed to end the nightmare for those who tested negative, before that nightmare became a reality."

Asked whether he had feared for his own life while in Africa, Zhang says he had no qualms, and anyway, any concerns he might have had would have disappeared by the time he finally arrived on the African continent after a plane journey of nearly 20 hours.

"It (Africa) was so far away that the plane had to land and refuel. While in the rarified air, we all came to the realization that even if any of us did contract Ebola, it would be virtually impossible for them to be flown home for treatment."

If living on canned food for two continuous months was hard to forget, the reception the Chinese team got upon arrival will live long in Zhang's memory. "As our vehicle passed a bazaar early one morning, throngs of locals came out from their humble storefronts and called out at us 'Ebola, China, Ebola, China'. I could almost feel the heat of expectation in their eyes. Looming right behind them were giant placards that warned, 'Ebola is real'."

It is indeed real. As of Feb 10, the outbreak has seen 23,034 suspected cases and 9,268 deaths. Yet for Zhang and his colleagues, every death should be accorded the same respect the person was given when alive.

"The local people are highly traditional, and funerals are seen as a central part of life's journey," Zhang says. "There were times when dead bodies were being tested for the Ebola virus in our lab while the relatives waited outside.

"If the result was negative, the family was still able to take the body of their loved one away for private mourning and hopefully, a proper burial," he says. "Love is immune to any virus."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn