Costa Rica provides a shining example for China soccer

|

Chinese soccer fans watch games in a bar in Shanghai. Gao Erqiang / China Daily |

Bars in Shanghai are crowded with football fans after midnight. Tens of thousands of taxi drivers working the nightshift in the city unanimously listen to sports radio that broadcasts the World Cup games.

China's absence in World Cup does not affect Chinese people's interests in the game. But what wracks Chinese fans' nerves most in the on-going games in Brazil may not be Spain and Italy's early knock-outs, but Costa Rica, which can serve as a reference point for China to know its position on the world football map.

Few would have believed that the small Central America republic could break through the encirclement of Uruguay, England and Italy as a leader of the "death team".

Costa Rica's team was not known to most Chinese until its striker, Ronald Gomez, a player active in Greek clubs, twice put the ball in China's net in Gwangju stadium in South Korea during China's debut in the 2002 World Cup.

Costa Rica's success so far this time has already stirred a wave of reflection on the failure of Chinese football.

China's ranking dropped from around the 50th in 2002 to the current 100th on FIFA's list. South Korea, Iran and Saudi Arabia used to be China's main competitors in Asia in the 1990s. Now the list includes Thailand, Vietnam, Singapore, Indonesia and Myanmar. Standing on the pitch of the World Cup seems like an increasingly difficult dream for China to realize. Costa Rica's performance this time inspires many Chinese to rethink the possibility of reviving that dream.

"We have time, money and fans. Let more children play football is the only way out for the game in China," noted a veteran football fan in a bar on Hengshan Road in Shanghai.

The question is how to attract Chinese children to the pitch, again.

Costa Rica's government has funded football schools since 1990 after it played in the Italian World Cup for the first time. Its economic rise in the 1990s ensures the sustainability of this fund that helps children aged 7 to 12 receive free training, life allowances and two free meals a day in the hundreds of football schools. There are 254 registered football clubs in the nation of about 4.5 million people.

Hundreds of Costa Rican players have joined famous soccer clubs in Latin America, Europe and Asia in the past 20 years.

China experienced a similar boom of football training for children in the early 1990s after the Chinese football team, coached by German coach Klaus Schlappner, showed its potential to "rush out of Asia and march to the world".

The spread of TV after the late 1980s also stoked football's popularity in China. The live broadcasting of the World Cup in Mexico in 1986, Italy in 1990, the United States in 1994, Italian Series A League and then the English Premier League after 1997, has nourished generations of fans in China.

China started its professional football league match in 1994. Chinese footballer's average annual earnings at top Chinese clubs have rocketed from several thousand dollars to about $1 million today.

But the prospering league match does not translate into a solid foundation of young talent, because of corruption in China's football world.

According to the Chinese Football Association (CFA), 650,000 Chinese children played football in various training programs in the country. The number dropped to 180,000 in 2005 and further until now.

This timeline correlates with the pace that the corruption and bribing extends from CFA officials, to referees, coaches and players.

Last year, two former heads of CFA and their colleagues, several referees and a number of national team players were imprisoned on charges of dereliction of duties and taking bribes. Several famous Chinese clubs have been punished for bribing CFA officials and referees.

CFA is supposed to be a civil organization. It has a close connection with the administration department affiliated to the General Administration of Sports in China (GASC). For a long time, CFA's chairman was also the director of the football administration center of GASC, a mayor-level official.

Details unveiled by judicial authorities show that club owners and players bribed CFA officials and referees for preferential treatment in a match, or to secure a seat in the national team.

In such an environment, few parents are willing to send their children to play football.

Now, China has only 20 football schools, down from 4,000 in mid 1990s, and 7,000 registered players in contrast with Japan's 600,000 and South Korea's 700,000 young registered player population.

But the clean-up does not necessarily make a big difference as the new CFA officials expect, whose bureaucracy has not changed much. The national team's good performances help promote the officials in China's sports administration system.

Changing a coach becomes the most effective way to help a team play better, CFA officials believe. Since the 1990s, nearly 10 coaches from China, Germany, Netherland, Serbia, England and France have coached China's national team.

It is the same for clubs owned by state-owned enterprises, such as Luneng FC, a club funded by a state-run power group in Shandong. Firing a coach is the fastest way to win games and get club officials promoted.

Private clubs, funded by real estate developers, are more efficient in management. Yet, the bubble of China's overheated property market is also passed on to the football circle.

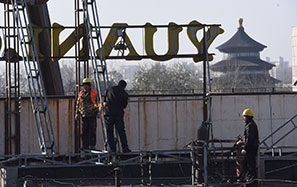

Nicolas Anelka and Didier Drogba came to play in Shanghai. Marcello Lippi has worked for the Evergrande FC, a club sponsored by a property company, in Guangzhou for two years. Lippi's team won the championship of the AFC Champions League last year, three years after its establishment, largely through buying good players from Brazil, Argentina, South Korea and Italy.

A number of retiring big names in Europe and South America have joined the gold rush to China. They do not help improve Chinese players' skills as past experiences indicate because few of them mesh into China.

Instead, they draw the rich clubs into a contest of buying famous players from abroad, which is regarded as the fastest way to improve performance. Poor and small clubs that have close connections to local kids and schools are quickly wiped out or squeezed to the lower level league match.

Luneng FC and Evergrande FC set up professional football schools in Shandong and Guangdong, respectively. Yet, most of the good players in China are from Dalian and Qingdao's primary and middle schools, thanks to their long football education tradition and local residents' trust.

China is good at producing Olympic champions with a state-run sports system copied from the former Soviet Union. Critics argue that the system should be reformed to play up the market's role in sports.

However, in the absence of the rule of law and effective supervision, the marketing of the football field infects the game with viruses that are common in many other sectors in the world's fastest developing country.

Football is a victim. So are the fans.

liyang@chinadaily.com.cn