Summit sets new course for future

Relationship between the us, Chinese leaders plays big role in changing game of world power

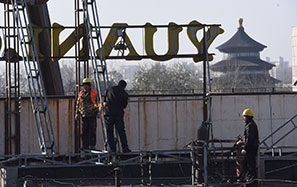

If former US president Richard Nixon's meeting in Beijing with Chinese late chairman Mao Zedong in 1972 ranked high on the meeting seismic scale, how should we measure the one in California earlier this month between the presidents of China and the US?

Was it just one of the dozens of routine meetings which take place between national leaders across the world every year? Or will it be remembered in decades to come as the beginning of a new era in Sino-US relations, and as an event of global significance?

In times gone by, personalities were highly significant in determining the evolution of history. The fate of Britain, and thus the outcome of World War II depended on the support provided by the Americans in 1940 and 1941. After its dollars ran out at the end of 1940, Britain, even with its empire, could not have continued to resist the Axis led by Nazi Germany without the decision by Roosevelt to provide ships and weapons to the British on credit.

Roosevelt's decision in 1940 to go on supporting the British was not just based on self-interest in maintaining a bulkhead between America and Nazi aggression. The deciding factor was his personal relationship with Churchill, which stemmed from the responsibilities that both men carried for their respective navies during World War I. Churchill's mother was American, making it quite easy for Roosevelt to relate to him.

More recently, in 1986 the meeting in Reykjavik between Reagan and Gorbachev, although inconclusive, revealed the lengths to which both sides were prepared to go. It provided a basis for trust between the two sides and paved the way for an end to the Cold War.

The Soviet Union had looked for cultural leadership to Europe since the time of Peter the Great, and its Western orientation also made possible a mutual understanding.

But in the case of Barack Obama and Xi Jinping, can two leaders from such different societies, with apparently few shared cultural values, build a strong relationship of trust in such a short time?

Much has been made in the media of the time in 1985 that President Xi spent in Iowa as part of a delegation from Hebei studying farming technology. It's certainly an advantage that the Chinese president spent some time in the American Midwest.

On the other side, President Obama's African father makes him very different to most American presidents, an outsider even in America's immigrant society. It may be easier for an outsider like Obama to reach out to and relate to a leader from a radically different kind of society.

Reports of the meeting indicate that the chemistry between the two leaders was good. Obama's post-meeting comment "terrific" also hints at a positive outcome. It looks as if both men, highly intelligent, well prepared and willing, were able to develop some kind of personal understanding.

What difference does it make, though, if the leaders of China and the United States like each other? Doesn't the huge governing apparatus that surrounds both of them make such personal inclinations irrelevant? Or will the Edward Snowden affair prove a dampener?

In America, Obama appears to have been largely neutralized by his political opposition, the Republican Party. In China, Xi only began his presidency two months ago. Yet in spite of the constitutional checks and balances set in place by the founding fathers of the US designed to make absolute rule impossible, Obama, as a second-term president, wields enormous power and influence.

For Xi, combining leadership of the government and the Communist Party with the army gives him an authority which, combined with his personal qualities of leadership, sets him apart. Each can have enough influence on their country's policy for their personal feelings to make a great difference.

When Reagan met Gorbachev in Iceland 27 years ago, the world was a relatively simple place, because all of it - outside of China, which was emerging from the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) - was controlled either by the Soviets or the Americans. Today, 23 years after the end of the Cold War, the post-crash economic weakness of the West, together with the growth of the emerging world led by China has made the world of the 21st century much more complicated. In Asia, the rise of India and China both challenge the recent economic supremacy of Japan.

Elsewhere, both Africa and South America have become significant political and economic forces, while Russia, by virtue of its geography and huge natural resource endowment, continues to play a major world role.

Meanwhile, the major powers that dominated the post-war period remain highly significant. Europe's financial problems drag on, and may not be resolved for years. Nevertheless, today, based on current prices, the European Union still generates 23 percent of global GDP, making it the world's largest single economic region and economically roughly twice the size of China. The G7, which includes Japan but does not include China, still makes up 46 percent of global GDP. Even by 2018, when China is projected by the IMF to occupy 15 percent of global GDP, the European Union will still count for 20 percent and the G7 43 percent of world output. It's too early to discount the G7, the EU and even Japan as global powers.

Since 2001, the war on terror and the financial crash have indicated, all too clearly, the limits to American financial and military power. President Obama's policy of withdrawal from existing military commitments in Afghanistan and Iraq and his reluctance to engage in new adventures overseas has set a new trend for American policy. America can no longer afford the massive foreign interventions of the post-war years.

Yet, as the war in Syria demonstrates, the world remains unstable. There's still a need for an effective capability for intervention that can deter aggression and maintain peace. The mounting trade war between Europe and China, and the failure to come to terms on a new global trade agreement to update and improve the Uruguay round of 1993 also call for urgent and forceful big-power co-operation.

The new global multilateralism recognizes greater international diversity, but at the risk of an increase in global instability. America, still by far the most powerful nation, needs help in maintaining global order. China's pressing security issues - Japan, the South China Sea and beyond it, the Pacific - all involve America. Even apart from the current hot issues of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, terrorism, climate change and cybersecurity, there is much that China and the United States can co-operate on to their mutual advantage.

In fact, it's becoming clear that the 21st century is not just the Asian century. It's the century in which, in an increasingly fragmented and diverse environment, the major powers and power groupings led by America, Europe and China must find common values and co-operate together in order to maintain peace and promote prosperity.

China and America both realize that each has too many problems for them not to find ways to work together. By arranging the meeting at Sunnylands, both recognized that the game has changed. In decades to come, we may give it a ranking of importance as high as the historic Mao-Nixon meeting of 40 years ago.

The author is a visiting professor at Guanghua School of Management, Peking University. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.