Reinventing the souvenir as an artisanal artifact

|

|

Between the queen's Diamond Jubilee celebration and the Olympic Games, this has been a banner year for British memorabilia. Sixteen dollars, more or less, will buy you a gelatin dessert mold in the shape of Elizabeth II's head. For about $2,440, you can furnish your bedroom with a handmade jubilee mattress covered in a Union Jack pattern.

Then there are the mass-produced trinkets that make up almost all of the estimated $1.5 billion industry of London Olympics souvenirs, from Union Jack bunting to stuffed versions of the Olympics mascot known as Wenlock.

Some of the most memorable designs this summer were, in fact, inexpensive souvenirs. They're the objects commissioned by Create, an arts organization in London that asked five designers to propose alternatives to the shoddy mementos from overseas.

The Create objects are significant because they do the work a souvenir is supposed to do, in terms of encapsulating a place and time. Yet they are not like the mugs or T-shirts we collect as reminders of historic occasions. Instead, they force us to consider what it means to commemorate, and whether the embodiments we choose are really worth the dust they gather on the mantel.

The pieces include Barnaby Barford's porcelain house modeled on the Blind Beggar pub in the London borough of Tower Hamlets, Andre Klauser's miniature cast-iron mooring post and Ed Carpenter's enameled pins printed with Cockney slang. All are tokens of East London, where the Olympic Park is, and created by designers who live or work there.

Dominic Wilcox's 25-centimeter vinyl record preserves the sounds of workers in 21 East London trades, from salmon curing to eyeglass making. And the Olympics are alluded to in Donna Wilson's series of "exercise books," notebooks with a map of East London parks where users can practice sports.

Souvenir collecting dates at least to the days when medieval pilgrims brought back tokens from their sojourns in holy lands. "Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition," a recent exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, displayed coinlike terra-cotta disks from the sixth or seventh century, possibly from Syria, that were gathered by pilgrims as remembrances of their encounters with holy men.

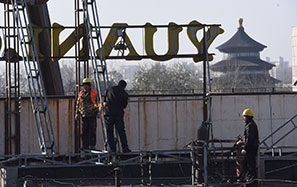

Today, most souvenirs are cheap objects mass- produced in Asia. According to The Daily Mail of London, only 9 percent of 194 souvenirs offered on the London 2012 Web site in February were manufactured in Britain; 62 percent were made in China.

But souvenirs can also be expensive items of long-lasting quality, like the Royal Crown Derby Diamond Jubilee tea set, which sells for $930.

Then there are prideful souvenirs like national flags, and snarky ones like the mold made by the British designer Lydia Leith, which produces the quivering Queen Elizabeth Jell-O head.

The Create objects occupy a completely different category. You could call them precious: behold the artisanal souvenir, subtly flavored and locally produced in small batches. Except that they have robust ideas and forms, and are reasonably priced: $16 buys you Ms. Wilson's exercise books, and for $23 you can have Mr. Carpenter's Cockney slang pins. (The items are available at theo-theo.com.)

Thorsten van Elten, who supervised the design and production of the Create souvenirs, said, "They had to be viable souvenirs." The objects are intended for a broad audience, which is also why they are affordable.

But despite the modest prices, these goods are meant to last. They express a desire to preserve vanishing cultural markers like Cockney speech and the sound of manual typewriters.

Constantin Boym, a designer known for his provocative works about souvenirs, uses the term "meta-souvenir" to describe objects, like those in the Create series, that provoke questions about the very act of remembering.

The Buildings of Disaster series, which Mr. Boym and his wife, Laurene, began producing in 1997, are a classic example. The bonded nickel models are of places that have been deformed somehow through horror, such as the New Orleans Superdome, which was damaged during Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

As the Create series showed, meta-souvenirs rarely kowtow to the usual monuments.

A matchbook by Tobias Wong in 2002 displays similar meta-souvenir hallmarks. It's mordant, witty and philosophically troublesome, shorn of all its matches, except for two sulfur-topped strips: a model of the World Trade Towers, ready to be ignited.

"It doesn't just sit on your shelf as a memorial," said Todd Falkowsky, the curator of an exhibition of Mr. Wong's work opening at the Museum of Vancouver in September. "It's provoking you to do or not to do something."

The New York Times