Super bugs

|

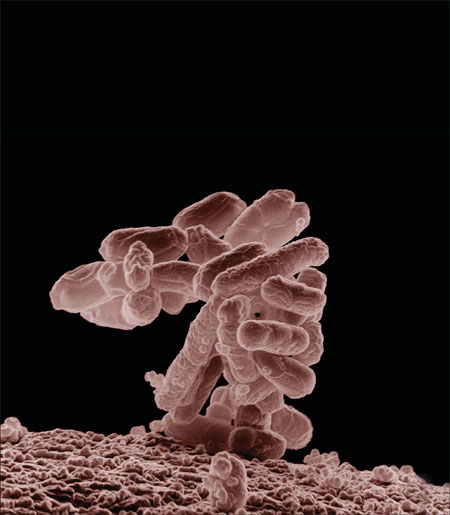

We don't think of E. coli (left)as a super bug, but strains of this fecal bacteria can cause stomach upsets and serious food poisoning such as in the fatal O157 outbreak in Germany in June. Provided to China Daily |

The next time you pop an antibiotic, consider this: You may be helping a dormant virus mutate into an even more lethal killer. Mike Peters tells you how.

First there is a sniffle somewhere across the room, and in no time everybody around you in the office is sneezing. Half the people crowded onto the subway look like they should be home in bed. At some point, as you stand next to someone having a coughing fit, you might be forgiven for wondering: Is this the start of the next killer virus? It's scarier than any Halloween scenario. While several centuries have passed since the Black Death, a bubonic plague, wiped out about half the population of Europe, more recent super germs have been plenty lethal. SARS, avian flu and H1N1 seemed to have come in quick succession - and made a mockery of the available arsenal of drugs. Despite astonishing advances in modern medicine, mutant strains of viruses and bacteria continue to threaten human lives today.

Wang Hufeng, director of the Health Reform and Development Center at Renmin University of China, says new strains of drug-resistant "superbugs" are able to spread rapidly here and around the world because of air travel and the globalization of food sources.

But the biggest problem, he said at an International Health Leadership symposium this summer in Beijing, is the nation's "reckless overuse of antibiotics" in the health system and in agricultural production.

Let's roll back the years to a fine afternoon about eight years ago.

Feb 21, 2003, dawned a relatively happy day for Liu Jianlun, a 64-year-old Guangdong doctor who had arrived at Hong Kong's Metropole Hotel for a wedding. Despite flu-like symptoms similar to those of patients he' had been treating at home, Liu felt well enough to travel, do some shopping and see the sights with his brother-in-law.

A day later, feeling much worse, he went to a hospital emergency room and was admitted to intensive care. He died on March 4.

On March 1, his 53-year-old brother-in-law was admitted to the same hospital, and 18 days later he was dead, too.

The monster virus SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) was just beginning its ugly march around the world. About 80 percent of the Hong Kong cases were traced back to Liu, and a man who stayed across the hall from Liu's hotel room traveled to Vietnam and launched the disease on a global tour that lasted more than a year. A young woman staying in the same hotel as Liu became Patient Zero in Singapore.

China's Health Minister Zhang Wenkang was sacked in a shakeup triggered by criticism that officials responded too slowly to the outbreak. Vice-Premier Wu Yi was appointed to take over crisis management, which she did with ruthless efficiency. Beijing's mayor also was replaced, blamed for failings that included not tracing people exposed to those infected.

While the lessons learned from SARS have been widely reported, and defenses against future outbreaks are much improved, public health officials around the world warn that air travel and overuse of antibiotics could give the next superbug a huge running start.

Why are antibiotics the bad guys?

Because their widespread use is a big reason for the emergence of resistant bacteria that public health professionals call MDROs, or multiple-drug resistant organisms.

The presence of antibiotics stimulates bacteria to share genes that resist it, and that evolutionary pressure has both spread resistance and prompted new strains that shrug off the drugs now available in our pharmacopoeia. Citing high levels of drug resistance in China, Wang says, "even third- and fourth-line antibiotics are not working".

A key problem is that patients crave antibiotics whether they are needed or not.

Antibiotics are drugs that are anti-bacterial, and have no effect on viruses. Wang cites a China study in which "three out of five chemists agreed to sell antibiotics after a cursory consultation with the 'patient' who complained of a sore throat".

This irrational drug-taking is not new, he says. Antibiotics became mainstream drugs between the two world wars. The fear of biological and chemical weapons - and the specter of nuclear weapons - had common folks scrambling for the most powerful cure-alls they could get their hands on. The promise of quick relief and the opportunity to get back to work or school keeps antibiotics on top of most consumers' wish lists today.

Wang says that in Chinese hospitals, 60 percent of in-patients are prescribed antibiotics, compared to the WHO guidelines of 30 percent. Other experts say 30 to 50 percent of antibiotics prescribed worldwide are unnecessary. Such abuse happens everywhere, and it's not simply a case of wimpy doctors being bullied by patients.

The primary cause of overuse of antibiotics in China, Wang says, is the country's under-funded healthcare system, "where hospitals derive up to half of their operating income from selling drugs".

If you are struggling to feed your family, he says, you may give the best medical advice you can but still bend to the pressure of patients who insist on antibiotics. That's why reforming the way doctors and hospitals earn their income is critical to stopping the overuse of these drugs.

Gordon Liu, a Chinese professor and health-economics researcher at Peking University, says prescribed drugs represent about 20 percent of health-care costs globally but can account for 50 percent of what people pay for health care in China.

"Antibiotics are quite a big part of that," he said.

If our bodies build up immunity against antibiotics, it means the drugs are less likely to work next time we have a bacterial infection. And while people tend to think of H1N1 or bird flu when we talk about "superbugs," Beijing physician Richard Saint Cyr says "we in public healthcare are mostly talking about the very common bacterial infections that are slowly becoming immune to most antibiotics.

"The most common problem is MRSA (methicillin-resistant staph aureus)," says Saint Cyr. "This is a very common skin infection, and now a lot of healthy young people are developing much more severe skin infections because it's harder to treat than it was 20 years ago."

Dr Yu Yunsong, vice-president of Shaoyifu Hospital in Shanghai, says about 4 percent of hospital infections in children and 7 percent of such infections in adults are caused by the so-called superbugs.

Speaking at the same International Health Leadership symposium which Wang addressed in July, Yu said there are "at least eight definitions" of superbugs and three professional classifications: MDR resists three classes of drugs, XDR resists all but one or two, and PDR (pan-drug resistant) is not controllable by any drug we have now.

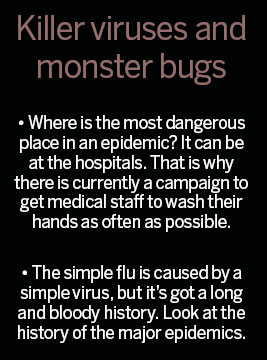

Most people recognize the potential threat of being stuck in a crowded subway or airplane next to a person with a raspy cough. But bacteria and viruses get passed around in other ways, too.

The unclean hands of doctors and other health workers have been associated with the spread of resistant organisms - one reason why hospitals can be unhealthy places to be.

Farm animals, particularly pigs, are believed to be able to infect people with MRSA, for example. The resistant bacteria in animals due to antibiotic exposure can be transmitted to humans via three pathways: through the consumption of meat (and milk and eggs), from close or direct contact with animals, or through the environment.

In these days of great medical advances, can the next "SARS" or the next "Ebola" be stopped?

As Saint Cyr noted, it's not always the most exotic pathogens that pose the biggest problem. And while a pathogen like H1N1 dominates headlines for a year or more, dengue fever kills many more people in China.

That doesn't mean the next superbug or monster virus isn't worrisome.

About 25,000 people in Europe die every year from bacterial infections that do not respond to antibiotics, and most cases occur in hospitals.

Wang says he's not sure such outbreaks can be completely prevented, "but the response will be much better" as people become aware of the dangers.

In China, there is now more awareness and better transparency in the public health system in the wake of SARS and subsequent outbreaks, he says, and international cooperation and communication take place at high levels.

He points proudly to Renmin University's School of Public Administration and Policy, which just celebrated its 10th anniversary. Wang is deputy director of the school, China's first with a graduate-degree track in health policy. It has more research funding than any other school at Renmin, he says, and boasts 1,700 students, including PhD, postgraduate and undergraduate degree candidates.

More education, better hospital ventilation, changing the way health-care professionals are compensated and increasing vaccinations are all ways that pathogens can be controlled and antibiotic use could be curbed, experts say.

But while it's important to develop new drugs to fight the emerging superbugs, "new antibiotics and vaccines are no panacea," says Dr Michael Gusmano, director of the US Alliance for Health and the Future.

Although there are effective vaccines for influenza, vaccination rates are low even among high-risk groups such as the elderly, Gusmano says.

Wang says new Ministry of Health guidelines are aimed at putting the patient's needs first. But the key, he says, is to change the whole outlook on health care - from citizens to companies to schools to government.

"If people can't afford to take sick days, or companies won't allow it," he says as an example, "then as a society, we are not doing what we can to prevent the spread of these diseases."

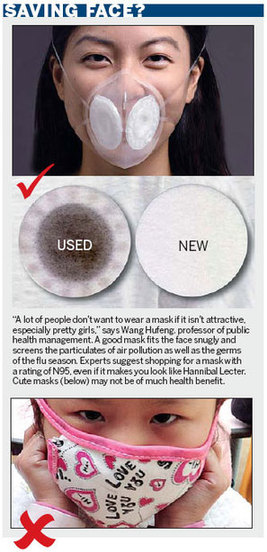

Stay healthy, the experts say. Avoid exposure to sick people. Isolate yourself when you are sick. Wear a mask in high-risk conditions. Like in football, the best defense is a good offense.

You may contact the writer at michaelpeters@chinadaily.com.cn.