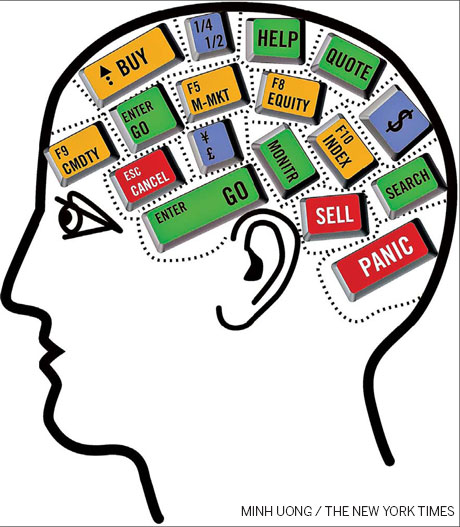

Markets gone wild? blame primal circuits

Updated: 2011-08-14 07:47

By Julie Creswell (The New York Times)

|

|||||||||||

Bradley Alford, a money manager in Atlanta, just hit the panic button.

No, really. Mr. Alford just hit the key on his computer that initiates the Wall Street equivalent of the nuclear option: sell everything.

He was acting on orders from two wealthy clients who became so alarmed by the troubled outlook that they wanted out. In recent days, they asked him to sell all of their stocks and invest in a mutual fund that is somewhat insulated against a market collapse.

"I have never, ever done it before," says Mr. Alford, chairman of Alpha Capital Management. "This was unprecedented."

Finance professionals are forever telling people to keep putting money away in retirement investment plans and to keep believing, whatever the market's daily ups or downs. But even they have been having second thoughts.

Wild plunges and gyrations in the world's stock markets recently, and a downgrade of America's credit rating, had everyone asking: What is going on? Evidence that the American economy is bad and growing worse has been piling up for a while now. And it's not as if we didn't know Europe had a debt problem. Why, then, all these crazy swings?

One possible answer comes from, of all places, the fields of psychology and neuroscience. In recent years, an area of study called neurofinance has tried to use brain science to explain how our primal circuits can override our reason when it comes to investing.

Many experts say the 2008 financial crisis recalibrated investor psychology. After living through the collapse of Lehman Brothers and the panic that followed, some investors are apt to sell first and ask questions later.

The result: the markets go wild.

Dick Del Bello, senior partner of Conifer Securities, a company that provides support to hedge funds, says these funds have started to place more wagers against the markets, if only to protect themselves. But as a whole, he says, they are still betting that stocks will go up, rather than down.

"Hedge funds decided to add to their short positions and play more defensively," he says.

Confidence is fragile, in other words.

Denise Shull, the founder of Trader Psyches, which consults funds and investors on neuroscience strategies, says many investors are using the 2008 panic as their new reference point. After so many people lost so much money, many investors no longer hesitate to sell at the first sign of trouble, he says.

"How your brain deals with uncertainty - when it recognizes it is in an uncertain situation - is that it tries to pull it from a bigger context," Ms. Shull says. "The context of 2008 and not wanting to see it happen again would absolutely influence these people to hit the sell button. Then it becomes self-fulfilling for the market."

It has actually been relatively easy to make money on Wall Street over the last year or so. Buoyed by hopes that the United States Federal Reserve would be able to reignite growth through its controversial bond-buying program, the American stock market shot up last August and kept on rising through this May.

That run gave investors a false sense of security, says Roy Niederhoffer, who runs R.G. Niederhoffer Capital Management.

Mr. Niederhoffer, who has a degree in computational neuroscience from Harvard University, says he was surprised at how complacent investors have been.

One measure of that complacency is the Chicago Board Options Exchange's VIX index, which uses the price of stock options to measure investors' expectations about future volatility.

After spiking following the earthquake in Japan this year, the VIX drifted lower through June and remained relatively subdued until early July. It has since shot up.

Richard Sylla, a finance professor who has written about market sell-offs, said recent stock market plunges have had all the hallmarks of panic attacks.

The debt-ceiling debate, concern over the American economy, Europe - the bad news just kept coming, and investors finally snapped.

"When you pile all of those things together, investors become queasy," he says.

Mr. Niederhoffer agrees. "I think, without question, there's been a tremendous shift in psychology, but it took a while," he says.

Mr. Niederhoffer has actually had a tough time because investors have been so complacent. He uses what is known as a contrarian strategy, moving against the crowd. Now he smells opportunity.

"We see what's happening as a return of the psychology of the markets in 2007 and 2008," he said. "This feels like it's got legs."

If he's right, investors had better fasten their seat belts.

The New York Times

Hot Topics

Anti-Gay, Giant Panda, Subway, High Speed Train, Coal Mine, High Temperature, Rainstorm, Sino-US, Oil Spill, Zhu Min

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|