Sounds of tradition

|

Ulaantug leads the symphony orchestra from the Inner Mongolia Nationality Music and Dance Opera Troupe to introduce the music from grassland. Zhang Ling / Xinhua |

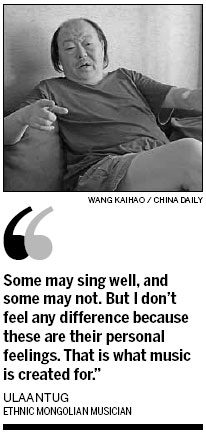

Ulaantug is the musician behind some of the most iconic music about the grasslands of Inner Mongolia. He tells Wang Kaihao and Yang Fang in Hohhot, why he is passionate about taking ethnic Mongolian music to the wider world.

He has scruffy hair and is dressed casually in shorts.

It is hard to believe this man from the Mongolian ethnic group who cares little about his appearance is the person behind so many widely loved pieces of music about grasslands.

There might be some people living in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region who have never heard the name Ulaantug, but it would be difficult to find someone unfamiliar with the mesmerizing rhythm of The Great Hulunbuir Grassland, which venerates the remarkable landscapes in the region covering vast areas of northeastern Inner Mongolia and recalls the locals' collective memory of their homeland.

Ulaantug, 55, was born to a musical family from Hailar, deep in Hulunbuir. He feels a strong emotional attachment to this green land.

"I am only a shepherd of music," he jokes. "The most important thing is to spread my music widely among the public. It is extremely exciting when I wander around the grassland and find herdsmen are singing my songs."

In 1999, Ulaantug cooperated with Xi Murong, an ethnically Mongolian poet from Taiwan, to create one of his most renowned pieces, Father's Grassland, Mother's River. It swept folk music circles overnight via 2000's CCTV Spring Festival Gala and has now become a staple sung at Inner Mongolia banquets.

"They will not think of me but always connect their own memories of grasslands to the scores," he says. "Some may sing well, and some may not. But I don't feel any difference because these are their personal feelings. That is what music is created for.

"Thinking weighs more than creativity. My music is the channel shedding the emotion, and writing scores will thus be easy. But the expression of affection cannot be overdone. It comes from nature, and it should be natural."

Keming, a lyricist who has worked with Ulaantug for many years, once said: "Ulaantug uses scores to write poems. I can see pictures via the melody. His music adheres to herders' feelings in a very low profile. It is not tawdry and will surely win a great life. His awards are bestowed by herdsmen, which is more precious than anything else."

Ulaantug is the first composer from non-Han ethnic groups to hold a concert in Beijing's Great Hall of the People. However, Ulaantug says he cares little about these type of achievements, he does not even categorize his manuscripts.

"Perhaps I should because many manuscripts are missing," he laughs. "But I use my musical language to repay my homeland and cheer people up. That is good enough."

In Ulaantug's eyes there are two ways to revitalize ethnic music: One is to collect the folklores scattered in the grassroots, and the other is to use modern genres, like symphony, to explain traditions. He prefers the second method, because of his own academic study of western classical music and his 11 years' experience as an instructor in an orchestra based in Hohhot, capital of the autonomous region.

When his music in Hulunbuir Symphonic Poems was played in 2007 at Golden Hall, the Musikverein in Vienna, Austria, he remained calm as the Western audience cheered. He continues to search for multiple ways to make Mongolian melodies heard globally. As an accomplished piano, violin and cello player, as well as a master of Chinese musical instruments like erhu and horse-head fiddle, he is a qualified candidate to bond different cultures.

Ulaantug is among the co-organizers of Hohhot-based Grassland Cultural Protection and Development Fund of Inner Mongolia, which is devoted to reviving traditional Mongolian ethnic cultural heritage and enhancing their communications with overseas counterparts. He has also devoted much energy in recent years to promote World Music, a relatively new term describing the world's ethnic music.

He is currently composing for a romantic opera Baigalmaa, which is to be staged in Beijing's Poly Theater in September. The program, led by China Opera, will be his opera debut.

"We don't have to strictly follow Western disciplines," he says. "All arias in this new work are based on Mongolian ethnic music, but we will use Western formats to make it accepted by senior opera fans. As long as the music is attractive, a simple storyline will make it popular. "

However, he confesses this is only a trial to combine Mongolian ethnic music and its European counterparts, and believes it will trigger more relevant in-depth comparative academic research if the trial is successful.

"The movie Titanic made Scottish bagpipes popular around the world," he says. "Maybe more operas on Mongolian ethnic group will have the same benefits on our traditional musical instruments."

He says the adaptation should be rooted in a deep understanding of an ethnic group's history, culture, and values, and expects the opera will be well received by overseas audiences.

Contact the writers at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn and yangfang@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 07/28/2013 page4)

Registration Number: 130349