Macadamia grows farmers' incomes

De'ang ethnic group have overcome impoverished lives by their own initiatives and government support programs

Editor's Note: As the People's Republic of China prepares to celebrate its 70th anniversary on Oct 1, China Daily is featuring a series of stories on the role regions have played in the country's development and where they are today.

Australia is far away, but the word "Australian" is often on the lips of villagers at Santaishan township, home to a large population of the De'ang ethnic group.

The macadamia nut, called the "Australian nut" by villagers in recognition of where it originated, is widely planted in Santaishan. Growing the nut is one of many ways that local residents have been lifted out of poverty in recent years.

|

The Jiaohua Festival is one of the most important traditional festivals of the De'ang ethnic group in Yunnan province. Photos Provided to China Daily |

|

De'ang people celebrate the Shaobaichai Festival. |

Located in southwestern Yunnan province, close to the Myanmar border, the township is surrounded by mountains and shrouded by clouds and mist almost every morning.

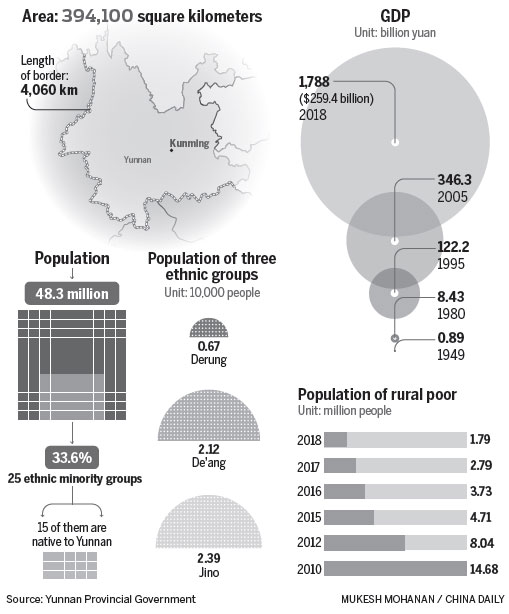

Around 60 percent of its 7,593 people belong to the De'ang ethnic group, accounting for one-fifth of all De'ang people living in China.

A total of 2,481.4 hectares of macadamias are planted near the township, producing 833.2 metric tons of the nuts, selling for 10 yuan ($1.44) to 12 yuan per kilogram, according to the local government.

It has become one of the farmers' main sources of income along with sugar cane, tea, passion fruit and livestock.

The idea of growing macadamias in the province germinated in the 1990s in the village of Mengzhi after one local man read a magazine article about the environment needed to grow them, and the high prices the nuts fetched.

Today more than 174,667 hectares are under cultivation in Yunnan, and revenue from the nuts is benefiting those ethnic groups living in remote areas, such as the De'ang.

The De'ang and two other ethnic groups, the Derung and Jino, were in April declared to have come out of serious poverty.

Strong demand

Li Sanxian, a member of the De'ang ethnic group from Lujiesa, a village in Santaishan, started planting the nuts in 2006. He now has 1.8 hectares of macadamia trees which can yield nearly 180,000 yuan worth of crops every year.

Li said he heard about the nuts in 2006 when government officials introduced them to the villagers, along with the idea of growing them together with tea.

His family planted sugar cane and corn in the past, but the returns were modest when compared with macadamias.

"Another thing is, not much time and labor is needed to take care of the nut trees," Li said.

"You just have to fertilize and spray them with pesticides twice a year and use white lime to paint the trunks in case ants and bugs gnaw at the tree."

Li added that after the trees bear fruit they have to be surrounded by an electrified fence to stop rats and squirrels eating the nuts.

He said he started growing pineapples in 2017, but it was labor intensive and the rewards were small.

Chuan Jiazhou, an official at the bureau of forestry and grassland of Mangshi, capital city of Dehong Dai and Jingpo autonomous prefecture where Santaishan township belongs to, said there was no need to worry about macadamia sales.

"It's popular in the international market," Chuan said in a June interview with Xinhua News Agency. "Dehong is located in the Northern Hemisphere, with its season the opposite of the major planting areas of Australia."

Reaping rewards

Party official Xian Yongming of Mangshi has been helping with poverty alleviation work in Chudonggua, a village in the township, since March 2018.

He believes that once motivated, the villagers can earn enough for food and clothing given they have planted on average of 0.33 hectares of macadamia nuts.

The trees usually begin to bear fruit three or four years after they are planted. Their yields increase until they reach a peak in their eighth year, Xian said.

The impact of the macadamias in helping relieve poverty in Santaishan is already being seen.

Most of the villagers have moved into new homes and own motorcycles or cars. In their homes they have access to clean water, electricity and the internet, although memories of cobbled roads, thatched huts, barefoot children and food shortages still linger in their minds.

Government statistics show that the average annual income last year was about 7,000 yuan, triple what it was a decade ago.

Bao Yanhua, a local government official, said the provincial Five-Year Plan (2016-20) to implement preferential policies to lift ethnic minority groups out of poverty had greatly helped the De'ang people.

Be my guest

The guesthouse of Li Chengming's family in the village of Chudonggua has been busy even though it only opened late last year.

As part of the ancient village protection project, 20 traditional De'ang residences are being strengthened and renovated and turned into guesthouses or culture and lifestyle exhibition venues.

The buildings are a traditional design, with four sloping eaves for water to flow down and a bottom level used to keep livestock.

Many of them were so old and rundown that they were torn down by the locals, who wanted to build new bungalows.

One guesthouse manager, Zhao Latui, 35, has learned how to cook traditional De'ang cuisine and make an indigenous concoction of fermented sour tea. Legend has it that tea is central to the cultural identity of the De'ang people.

Not only is Zhao keeping disappearing skills and customs alive, but he is also sharing his culture with his guests. He earns 100,000 yuan a year selling the tea.

Zhao also performs a traditional dance with water drums which is considered part of China's national intangible cultural heritage.

His guests come from as far away as the United States, the United Kingdom and South Korea.

Both Li's family and Zhao are aware of creating job opportunities for their fellow villagers.

Hanging tough

Yang Xiaoping, 28, hopes for an even better future.

She has been accepted into a doctoral program at Minzu University of China in Beijing to study linguistics.

Yang overcame many adversities growing up.

She lost her biological father and stepfather at a young age. Her mother Li Hongmei, 52, cannot write her own name, but all her three daughters now go to university.

Yang thought of dropping out of school when she was younger to help the family, but her mother persuaded her to stay on.

Li worked extremely hard, sometimes juggling several jobs, to support two elderly people at home and educate her three children who all worked part-time jobs.

Once when one of her daughters was reluctant to go to school, she took her to pick tea leaves to help her understand the "happiness" of going to school.

Yang struggled with the Mandarin language at school but managed to get on top of it.

But things have changed for De'ang students. They are now taught Mandarin from childhood, and all receive at least nine years of schooling. Government financial support is also provided to stop students from dropping out of schools.

Work continues

Yang Yan, a municipal committee member of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, says education is the key to prevent De'ang people from returning to poverty.

The ethnic group is in urgent need of teachers, doctors, judges and prosecutors. However, there are only about 60 members in a WeChat group of De'ang college students and graduates.

Yang Yan said preferential policies for university enrollment and civil service recruitment will help cultivate talented De'ang people to serve their own ethnic group.

Keen to study the phonetics of the De'ang language, Yang Xiaoping wants to both inherit and protect the culture of her ethnic group, which has its own language but without written scripts.

Many of the younger generation, especially those who live in the cities, don't speak the De'ang language now.

Yang Xiaoping says her little sisters, just several years younger than her, cannot speak the language well.

Contact the writers at fangaiqing@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily Global 08/05/2019 page5)