Familial link for Parkinson's disease discovered

Abnormal sleeping behavior may offer scientists more clues for a better understanding of the condition. Nora Zheng reports from Hong Kong.

Lok Sau-yung dreamed she was on a road walking toward a large pit. She feared that she might fall through the loose boards covering the top, but a worker reassured her that it was OK, so she carried on, and fell straight into the pit.

In reality, she had fallen out of bed, injuring her mouth so badly that seven stitches were required.

The 82-year-old was diagnosed as having rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder, known as RBD, since she was 66. People with the condition act out their dreams: They converse, shout, punch, flail and sometimes fall out of bed, which not only endangers them, but also their sleeping partner.

Lok's son Wong Li, 59, started showing similar symptoms nine years ago. His wife said he punched her while he was asleep, giving her a black eye. In the morning, Wong didn't remember a thing.

Though Wong has been told he is at a high risk of contracting full RBD and Parkinson's disease, he said the news has not made him anxious. He plans to retire this year and relieve the strain of hard work. In addition, he exercises regularly to improve his mood and sleep because he believes that doing something is better than doing nothing at all.

Wong's issues, similar to those experienced by his mother, may be genetic because first-degree relatives of RBD patients are at higher risk of contracting the condition. Not only that, a recent study reveals that the family trait places Wong at greater risk of Parkinson's disease than is normal among the population as a whole.

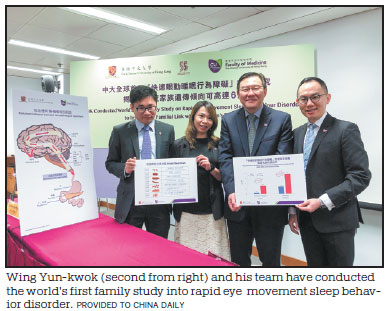

The study, the first in the world into RBD and families, was conducted by Wing Yun-kwok, a professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong's Faculty of Medicine. He and his team worked in collaboration with Sichuan University, Hong Kong University's Department of Psychology and McGill University in Canada.

The scientists invited 102 RBD patients and 89 individuals without the affliction, and 791 first-degree relatives. The subjects included the parents, siblings and offspring of those taking part in the study.

The researchers conducted sleep studies using polysomnography - a multiparametric test - and supplementary examinations, including the assessment of motor functions, olfactory testing and color vision tests.

Their results suggest that first-degree relatives of RBD patients are three to six times more likely to develop neurological conditions, including Parkinson's disease, than first-degree relatives of the healthy control group members.

Sleep cycles

People with RBD experience symptoms after a period of deep sleep when the eyes flutter rapidly, which is known as rapid eye movement, or REM, sleep.

Normally, humans cycle between non-REM sleep and REM sleep. A cycle normally lasts around 90 minutes for adults, and as the sleep cycles progress, the period of non-REM sleep lasts longer.

During non-REM sleep, little or no eye movement occurs, brain activity is relatively slow, breathing is regular, the heart rate is slow and blood pressure is low.

Both the brain and body are at rest. People rarely dream during non-REM sleep.

However, during REM sleep, the eyes move back and forth rapidly behind the eyelids, and although the body remains at rest, the brain is active. Recordings of electrical activity in the brain are similar to those taken during the waking state.

Dreams usually occur during REM sleep, a state normally characterized by muscle atonia, or paralysis. In such a state, if someone dreams they are being chased by a monster and tries their best to run away, he or she does not actually move. The state serves to protect the sleeping person.

That isn't the case for people with RBD. They don't have the protection of muscle atonia during REM sleep, so they act out their violent impulses in the dream state. This "dream enactment behavior" is characterized by excessive motor activity, ranging from simple limb twitches to violent, complex movements that may result in injury to the patients or their partners.

Abnormal buildup

In recent years, Wong Li noticed that his mother's hands and lips had started to tremble. This year, Lok was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease.

Joyce Siu Ping-lam, clinical assistant professor (honorary) at CUHK's Department of Psychiatry, said about 90 percent of patients with idiopathic - that is, resulting from an unknown cause - RBD may eventually develop other neurodegenerative diseases, especially a group known as alpha-synucleinopathies, which includes Parkinson's disease. This vulnerability can last from several years to decades.

These neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by the abnormal buildup of a protein called alpha-synuclein in neurons.

This can directly cause the death of cells in the midbrain that are associated with motor control, as evidenced early in the progression of Parkinson's disease, where the most obvious signs are shaking, rigidity, slowness of movement and difficulty in walking.

Vincent Mok Chung-tong, a professor at CUHK's Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, said research conducted over 20 years shows that Parkinson's disease is a slowly progressing degenerative disorder.

Problems first occur in the spinal cord, before moving slowly up to the midbrain.

However, before reaching the midbrain and causing Parkinson's disease and related symptoms, the condition triggers the loss of muscle atonia during REM sleep, which is a clinical symptom of RBD and indicates that the condition may be a precursor to Parkinson's disease.

Mok said their study of RBD is significant in ongoing research into neurodegenerative diseases. Most neuroprotective trials for neurodegenerative disorders have failed, because once patients start to develop symptoms, it's already too late for clinical intervention. There is a period of five to 15 years preceding the full onset of Parkinson's, so RBD potentially opens a window that will allow early assessment, intervention and additional studies to protect affected neurons.

Family study

The research conducted by Wing and his team is the first RBD family study to systematically investigate links with first-degree relatives to Parkinson's disease and other neurodegenerative conditions.

Traditionally, scientists have not considered Parkinson's disease to be hereditary, and studies show that only about 10 percent of people with the disease have a family history of the condition.

However, Wing's study has confirmed that RBD has significant familial connections, which is indirect proof of the inheritability of Parkinson's disease, said Zhang Jihui, assistant professor at CUHK's Department of Psychiatry.

In the study, scientists also found that even people without clinical symptoms of RBD displayed significantly more signs of neurodegeneration, such as constipation (defined as a frequency of less than twice a week) and subtle motor dysfunction.

"Parkinson's disease is a multisystem problem. The microbiome (microbes) in the gut may be the root of it. Constipation could be considered a preclinical symptom of RBD. It could take 20 years to proceed to Parkinson's disease," Wing said.

Neurodegenerative diseases are generally diagnosed according to clinical symptoms.

The pathology leading to the disease, however, may have started 10 years or more before the presence of significant clinical symptoms. Above all, the damage to the brain is likely to become significant and irreversible.

Even though researchers have yet to discover procedures that will slow neurodegeneration, they now have a direction to follow for more studies.

"If we can start screening high-risk individuals with RBD or other markers related to neurodegenerative diseases, we may be able to intervene at an early stage of neurodegeneration," Mok said.

Contact the writer at wanying@chinadailyhk.com

|

A volunteer (right) from Huazhong University of Science and Technology teaches a patient with Parkinson's disease how to use an anti-vibration spoon at a nursing home in Wuhan, Hubei province.Provided To China Daily |

(China Daily Global 05/27/2019 page5)