CULTURAL CENTERS BROADEN CHINESE HORIZONS

Overseas institutions aid accumulation of global knowledge

Editor's note: In a world facing increasing challenges on a number of fronts, such as isolationism and protectionism, different nations and cultures now have a stronger need and desire to get to know one another. In this series, China and the World: Learning and Understanding, we look at efforts being made globally to broaden mutual communication and understanding.

When Sinologist Michael Kahn-Ackermann became involved with establishing the Goethe-Institut in Beijing in the early 1980s, he said the task was considered as difficult as setting up such an institute on Mars.

The biggest problem was that the Germans and Chinese knew less about each other than they probably knew about Mars, he said.

Kahn-Ackermann arrived in the country in 1975 to study Chinese history, and later translated many bestselling works of contemporary Chinese literature in Germany, including Ferocious Animals by Wang Shuo and Dry River by Mo Yan.

He said setting up a foreign cultural center in China was very difficult and complicated, as there were many mutual misunderstandings, both from officials and the public.

After years of negotiations, the Goethe-Institut established its first branch in China at Beijing Foreign Studies University in 1988, the first foreign cultural center in the country.

Jia Wenjian, who in 1988 was a student majoring in German at BFSU, said he and his classmates were excited about the arrival of the institute.

"As very few Chinese university libraries had original German book collections then, the books and tapes from the institute were viewed as 'treasures' for us to practice our proficiency in the language," he said.

Jia, now vice-president of BFSU, said that over the past three decades, the Goethe-Institut has become one of the primary cultural and educational institutions for the promotion of the German language in China.

Clemens Treter, director of the institute, said its founding in China bore witness to the country's reform and opening-up, and its function has evolved along with the nation's development.

"As reform and opening-up changed how Chinese people view the world, the institute also has transformed from a simple language-teaching body to a window through which Chinese people can get to know more about Germany," he said.

Chinese have embraced a diversified global culture since the reform and opening-up policy was launched in 1978. They eat at any one of 2,400 McDonald's or 4,800 KFC outlets in the country, drink coffee at Starbucks or Costa Coffee, watch NBA basketball matches or soccer from top European leagues, along with Hollywood movies or Korean TV dramas.

Multiple choices

Chen Jie, a cultural industry analyst in Shanghai, said: "Compared with several decades ago, foreign culture is no longer a novelty for Chinese. They can easily get to know the world by surfing the internet or by traveling abroad, but they are still curious about what is happening in other places and are willing to pay to learn more."

The growing curiosity among Chinese about the outside world can now be satisfied without going abroad. Increasing numbers of foreign cultural centers are offering multiple choices for them to experience cultural diversity at home.

Treter said more space has been provided to the Goethe-Institut and many other cultural exchange institutions as part of China's continuing opening-up.

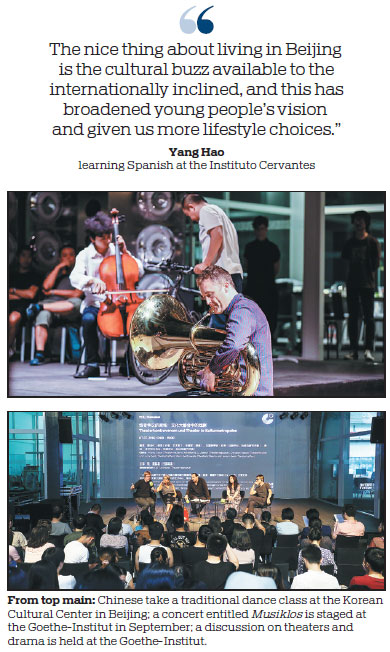

In 2015, the Goethe-Institut opened its flagship space in Beijing's 798 Art District. In a Bauhaus-style gallery, it hosts a strong, rotating program of art, music, films and literary events, with a focus on creating dialogue between creative people from Germany and China.

Last year, when the Goethe-Institut celebrated its 30th anniversary in China, it held a 30-hour "marathon" event consisting of concerts and other performances, installations, film screenings, lecture series, book talks and children's programs. Participants were asked 30 essential questions about a wide range of key issues.

Lin Zihui, an undergraduate in Beijing, attended a lecture at the institution entitled "Will Algorithms Soon Know Us Better Than We Know Ourselves?" that discussed how artificial intelligence and big data have changed every aspect of modern life.

Lin said attending cultural events at the Goethe-Institut has become a routine leisure activity for her.

"Walking into its premises in the 798 Art District on any given day, I can always expect to see something interesting and inspiring - like an independent German film or an art exhibition - all for free. For me, it's the best way to educate myself and be entertained," she said.

Many other cultural institutions are now also located in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, capital of Guangdong province. They not only provide programs to promote mutual understanding and linguistic comprehension between China and their home countries, but also enrich and entertain residents.

Zhang Mian, 36, and her son spend most of their weekends at the Institut Francais in the capital's Chaoyang district. While her 6-year-old boy is reading French author Jean Leroy's picture book Superfab Saves the Day in the institute's library, Zhang watches a French movie in its cinema. "It's important to me that my child can understand the different cultures around the world," Zhang said.

She signed her son up for many English classes, family camps or activities involving children during weekends. But she finally found the Institut Francais was the ideal place for herself and the boy to enjoy themselves. "It provides a space that is suitable for both adults and children to understand and improve their global awareness and communicate with a different culture," Zhang said.

Like Zhang and her son, the majority of those attending the Institut Francais do so for the language classes it offers, as French is one of the most popular foreign languages in China. About 100,000 Chinese are learning it, and about one-third of them have attended French courses at the center.

Yang Hao, 16, is learning Spanish at the Instituto Cervantes, just a few minutes' walk from the Institut Francais. He said he wants to study at a Spanish university because he has been a big fan of the soccer player Lionel Messi, who plays for Barcelona, since he was 10.

The Instituto Cervantes offers courses in Spanish as well as access to a library of Spanish literature and a wide range of lectures, film screenings, events and exhibitions.

"Luckily, my teacher at the institute is also a Messi fan. We have a lot in common, and by chatting with him my Spanish language skills are improving fast," Yang said.

"The nice thing about living in Beijing is the cultural buzz available to the internationally inclined, and this has broadened young people's vision and given us more lifestyle choices."

Chen, the Shanghai analyst, said residing in a big city such as Beijing or Shanghai can be stressful, as the cost of living and competitive working environment place higher pressure on the younger generation. However, she added that the abundant cultural resources in large cities can "vitalize" stressful lives, which is also a reason why many young people choose to live and pursue their careers in metropolises.

"Big cities with a vibrant culture - not just at the local and domestic level but also at international level - are a potent draw for citizens with global mindsets who can live anywhere but want to be in cities that are both stimulating and fun," Chen said.

From the younger generation to the middle-aged, Chinese are now willing to spend more to improve their quality of life.

A report in 2017 by international consultancy Mckinsey said Chinese living in cities were willing to spend not just money but also time on cultural experiences, acquiring knowledge and on educational courses in their spare time, not only to improve their skill sets but also to be entertained.

Tu Mei, 65, is a keen fan of the traditional Korean dancing class offered by the Korean Cultural Center in Beijing.

The retired accountant said she appreciates the confidence and beauty of women in Korean TV dramas, and this was the main reason she enrolled in a class provided by the center.

Han Jae-heuk, director of the Korean Cultural Center in Beijing, said it was formerly known as the Korean Culture and Information Center and was established in small office space soon after China and the Republic of Korea established diplomatic ties in 1992.

In 2007, the center moved to a four-story office building with two underground floors in downtown Beijing. As a cultural promotion organization, it has also become a soft power generator in China.

As director of the center, which aims to act as a bridge between the two countries' peoples, Han said his work involves promoting the depth and significance of Korean culture in a variety of fields, from traditional music and dance to modern films, dramas, cartoons and cultural industries, to food and fashion.

"As the center attracts international visitors, open-minded middle-class people and the younger generation who work in the city, we operate a wide range of programs to meet the needs of the mainstream," Han said.

K-pop, the musical genre from Korea characterized by a wide variety of audiovisual elements, is hugely popular among young Chinese. To attract them, the center has designed free training sessions for popular Korean dances and songs, and even Korean-style makeup classes. It takes just minutes to register for these classes online.

The center said it has hosted about 700 cultural activities and received more than 850,000 Chinese visitors since 2007. In the past decade, more than 24,000 students have attended its classes.

"It showcases how popular Korean culture is in China, but is also evidence of closer relations between the two countries," Han said.

Heated debate

In China, overseas cultural centers not only offer classes for foreign languages or culture. As people nurture higher cultural ambitions, more centers are aiming to become public spaces for discussion and dialogue on cutting-edge topics.

In May 2017, the topic of sex education triggered heated debate on the social media platform Sina Weibo when a Chinese mother said she felt awkward answering her son's question "Where do I come from?" As a result, the Danish Cultural Center in Beijing organized a series of exhibitions and discussions of how Denmark has dealt with sex education as a matter of public health and concern over the past 137 years.

The center invited Fang Gang, a well-known sexologist from Beijing Forestry University, to give a lecture on sex education and gender issues. Some 150,000 people watched the speech, which was livestreamed online.

Exhibitions at the center also struck a chord with young Chinese parents, as visitors were asked to complete questionnaires about "awkward moments" in sex education in their families.

More than 3,000 replies were gathered, highlighting how Chinese parents were falling short in telling their children about the facts of life, while schools were also lacking in teaching students about sexual intercourse, contraceptives and sexually transmitted deceases.

Eric Messerschmidt, director of the Danish Cultural Center, said, "With these topics, we present the Danish perspective on the matter and offer Chinese visitors a new way of thinking about the issues."

Along with the Danish institution, many foreign cultural centers in China are trying to define themselves as independent spaces for creative dialogue on topics of global relevance.

In 2014, when the Danish Cultural Center moved to the 798 Art District, a Chinese Cultural Center was built in the heart of Copenhagen, the Danish capital. It was the first Chinese cultural center to be set up in a Nordic country.

Messerschmidt said both Chinese and Danes are interested in sharing their culture.

"The generosity in sharing ideas and always discussing issues in a peaceful way have brought the Chinese closer to the world, because they always learn, interact and understand the world with an approach that is founded on respect," he added.

panmengqi@chinadaily.com.cn

|

From left: An exhibition, Age and the City, is held at the Danish Cultural Center in Beijing; a taekwondo class is staged at the Korean Cultural Center; Chinese students make kimchi at the Korean Cultural Center. |

(China Daily 04/12/2019 page2)