Satellite babies feel the pain of separate lives

Reunions can be traumatic for parents, children

Lindy Tse will never forget the night her parents brought her back to the United States from Fujian province when she was 4 years old.

She cried silently throughout the journey because she missed her nainai (grandmother), who raised her in China.

Tse, an assumed name, was a "satellite baby", which refers to children born in the US to Chinese immigrant parents who are sent to China as infants and raised by relatives - typically grandparents - and then returned to the US to start school when they are 5 or 6.

|

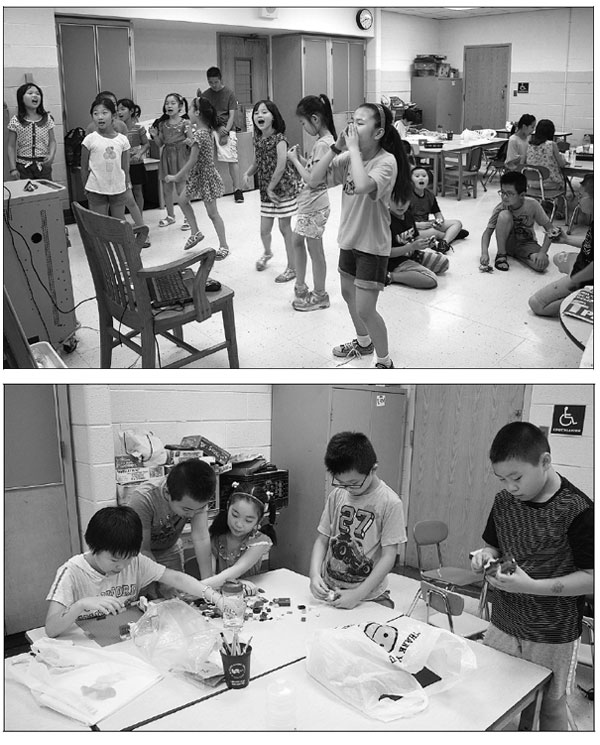

Top and above: Children sent to China as satellite babies sing, dance and play with toys at the Chinese-American Planning Council in New York. |

Parents do this for various reasons. They often work antisocial hours or have several jobs. They also want to send their children to China for cultural reasons.

On her return, it took Tse a year before she spoke to her father.

Now 17, she said, "I think it was because we had both lost four years that could have been important to our relationship."

She speaks only English now and has forgotten most of her early childhood spent in a small village with her grandmother. She still feels distantly connected with her parents.

"I just don't know how to show my emotions to them," she said with a shrug.

David Chen's parents sent him to Fujian to be raised by his grandparents before he was 1 year old. When he was 5, they brought him back to New York to start school.

Chen, now 26 and a student at Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine in New York, said: "I didn't know who they were - they were strangers to me. I was pretty distant with them."

To pay for him to go to China, his parents worked 14 hours a day at different restaurants, often seven days a week. The time the family spent together was limited.

By the time Chen started in the third grade, he was starting to have suicidal thoughts because of being separated from his grandparents, the difficulty of learning English, and bullying at school.

But instead of sharing his thoughts with his parents, he chose to keep his feelings to himself. "I definitely had my emotions bottled up," he said.

A mother working in Boston's Chinatown, who requested anonymity, sent her son to her hometown in China after he was born in the US. "Even though I missed him all the time, there's just no way you can get everything you want. You want to make money, but you also want to take care of your kid ... so we had to give something up," she said.

The term "satellite babies" was coined by Yvonne Bohr, a clinical psychologist at York University in Toronto, Canada, who has been studying such separations since 2006.

"Babies are often sent away at around the time they have just developed a strong attachment to their biological parents. As a result, they may experience distress during this separation," Bohr said.

"When they return, the parents in turn may expect the children to be very happy to be home, often not understanding that for the child, this isn't home," she said.

Research suggests that a "satellite" upbringing can disrupt a child's environment, which can lead to depression, anxiety and misbehavior at school.

Studies show that the trauma experienced by both children and parents can last a lifetime.

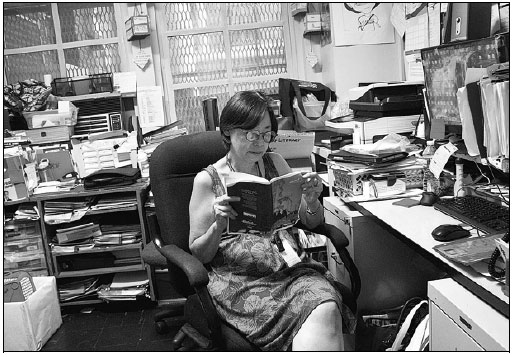

Lois Lee directs the Chinese-American Planning Council school-age child care program in Queens, New York.

Founded in 1965, the council is a nonprofit that provides support to Asian-American, immigrant and low-income communities in the city.

Lee, who has worked with immigrant families for more than 50 years, said 70 percent of the children now at the council are Asian-Americans, of which about 70 percent are satellite babies.

In her career as a teacher and administrator in this field, Lee has worked with immigrant families and helped thousands of children, including Tse and Chen.

She said most parents of satellite babies work long hours every day and cannot afford child care, the cost of which in New York ranges from $11,700 to $14,144 a year, respectively, for child and infant care, according to the Economic Policy Institute, a nonprofit think tank in Washington.

"These young couples work long hours at jobs in restaurants, nail salons, grocery stores, dry cleaners and hotels, doing work that no one wants to do, and yet they can't get childcare services for their families to keep the children here," Lee said.

She said reunions can be difficult for both parents and children after a long-term separation.

"They (parents) didn't see their children's first steps. They didn't hear them when they first learned how to talk. They lost five years bonding with them," she said.

Even after they live together, parents cannot always manage to take care of their children, and continue to work long hours to secure a better future.

"The parents still work until 9 pm... they come home late and the children have to have dinner by themselves, eating food that has been prepared," she said.

Some children feel guilty because their parents cannot take care of them.

"They feel they are a burden to their family, and they think: 'Why did you bring me back here? You don't want to spend any time with me'," Lee said.

The council's operating hours run from the end of the school day until 6 pm and it also opens on holidays when schools close.

The staff members perform tasks that parents would normally do, but which they do not always have time for, such as helping with homework, going for walks or to the movies.

"We are like the children's substitute parents. We try to help them embrace their identity, appreciate how hard their parents work, that their parents did not want to give them up, but they had no choice," Lee said.

The children are told that even now they are back, their parents are still making sacrifices, but this does not mean that they have stopped loving them.

Lee added that she thinks the children could show more understanding of their situation.

Chen said that being a satellite baby had strained his relationship with his parents, but also made him more independent.

"It made me understand why my parents did what they did when I was younger, in terms of working hard and sending me to China as a satellite baby," he said.

"My parents and I are now getting on better. Both my sister and I are best friends and we get along really well."

The council offers classes to help parents better communicate with their children, and to discipline them.

Lee said she does not expect these parents to create a family atmosphere like US families do by eating dinner together or adopting a full set of bedtime routines, "but at least they should talk to their children and (they should) try to understand each other.

"Children need to know their parents love them and want to talk to them," she said.

In the book Satellite Baby, written by students at the council and published in 2017, the main character comes to live with her parents in the US when she is 6, leaving her grandparents in China. "I haven't felt like speaking since," she laments.

After living with her parents for four years, they still feel distant, she is still scared of the dark and has trouble sleeping.

But the family eventually grows closer and the character takes on the duty of babysitting for her newborn brother, who was not sent to China to become a satellite baby.

She states: "We don't need the money. I love being part of this unique family."

xiaohong@chinadailyusa.com

|

In a career spanning nearly 50 years at the council, Lois Lee has worked with immigrant families and helped thousands of children. Photos by Hong Xiao / China Daily |

|

A young couple sends their child off to China at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York. Provided to China Daily |

(China Daily 03/27/2019 page2)