CHILDREN MAKE EARLY START AT LEARNING ENGLISH

Many students take lessons before reaching school age

Chen Yilin, who turned 3 in November, was sitting alongside six other children on the floor of a kindergarten classroom at an educational institute in Shanghai that caters to Chinese youngsters learning English.

"Who has a lizard?" the teacher from Canada asked the children, all of them younger than 5. Several shouted one after another, "I've got a lizard."

They each had a card with six pictures, and the first child to collect six objects from the teacher corresponding to the pictures on their card would be the winner.

Chen's mother, Zhou Moyi, watched her daughter through the classroom window.

"She has made huge progress since I decided to let her start learning English by sending her to classes twice a week eight months ago and by trying to talk to her in English as much as possible," Zhou said.

Many kindergarten pupils are learning the language before they start school, and an increasing number of educational institutions are holding English lessons.

Each claims to have the best teachers who are native English speakers. Some promise that their students will acquire an impressive English vocabulary within months.

Adele Bai, president of Kids & Teens at EF Education First China, said 40 percent of Chinese children now start learning English before school age, and many of them are from first-tier cities.

Children in big cities are only 3 when they first attend classes, younger than those taking lessons five or 10 years ago, Bai said.

"Back then, many parents would say, 'We may consider sending our children to learn English at 5 or 6, or when they lag behind in school tests'," she said.

Bai added that with the introduction of the second-child policy, parents do not want their children to miss the opportunity to learn English. She also believes the market will continue to grow rapidly.

VIPKid, a domestic online education platform that employs 60,000 North American English teachers to give one-on-one lessons, said the number of its students younger than 6 has been rising since 2013 - when the startup was founded - and has reached 70,000 nationwide.

According to the platform, "Most students are from big cities, such as Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen (Guangdong province), while those from Hangzhou (Zhejiang province), Chengdu (Sichuan province) and a number of smaller cities has risen by leaps and bounds."

EF Education First China, which claims to be the first to offer English training for children ages 3 to 6 on the Chinese mainland more than 10 years ago, said it has over 150 branches in second- and third-tier cities, and has achieved double-digit growth annually in recent years.

Bai said, "We upgraded our classes for 3 - to 6-year-olds nationwide in December, enabling confidence-building, personality formation and development of social skills in an immersive language environment, in response to parents' expectations of their children's all-around development."

Zhou said her aim in getting her daughter to learn English at such a young age is that she hopes that when she wants to express herself to people from anywhere in the world in the future, language will not be a barrier.

Zhou, whose English skills are outstanding and who started to learn the language in the third grade in primary school, said she was motivated by peer pressure.

"A year ago, when I took my daughter to a dinner with friends and their kids ages 2 to 4, they were all talking in English with their children," said Zhou, an editor at a foreign media outlet.

Another observation is that when the real economy subsided, a host of stores were replaced by educational institutes for children, many of them offering English classes, Zhou said.

Some school teachers have switched to such institutions.

Li Lin, who taught English at a bilingual primary school in Shanghai for five years, is one of them. In July, she started to teach at an institution specializing in helping children ages 4 to 15 form reading habits and improving their reading ability.

She said she was mainly prompted to change jobs because what she taught in class was strictly controlled. "I felt we were preparing the kids for exams rather than helping them to widen their ability.

"I believe such institutions are a necessary addition to school education, as children in most schools, especially public ones, only read textbooks, which makes it hard for them to form the habit of reading other books," she said.

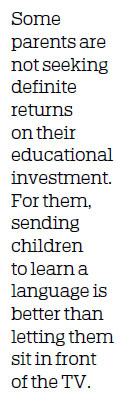

Some parents are not seeking definite returns on their educational investment. For them, sending children to learn a language is better than letting them sit in front of the TV.

Lin Peiqian, a mother in Shanghai, said: "My husband and I arrive home after work no earlier than 7 pm. There are three hours when my 4-year-old son and 2-year-old daughter can only stay with grandparents or the nanny. So I'd rather send them to learn something."

Lin said she and her husband spend about 40,000 yuan ($5,836) a year for both children to attend English classes.

Standard varies

Some parents said they had encountered problems at educational institutions, including foreign teachers who frequently changed jobs and some who were obviously not native English speakers.

Li said she worked part time at an institution in the summer holidays, when the number of foreign teachers was insufficient to meet the sharp growth in the number of pupils.

"The standard of foreign teachers varied greatly, and the threshold was not high. But in their advertisements, each institution said it only hired native speakers with teaching experience of a certain number of years," she said.

A foreign teacher working at an institution in Shanghai, who gave his name only as James, said he is an exchange scholar on an educational program at a nearby university. He chose to work at the institution to enrich his experience in China.

"I had previously worked as a one-on-one home tutor for Chinese kids. I now have the opportunity to meet more children and their families," said James, who comes from the United Kingdom.

He said that some colleagues are clearly not native English speakers and have passports issued by a range of countries. But some of them have TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) or TEFL (Teaching English as a Foreign Language) qualifications.

"However, they are not qualified to teach in international schools, which require teachers to be native speakers, and some recruit graduates from teaching colleges only," said James, adding that teachers with institutions where English is taught are paid nearly 20,000 yuan per month.

Wang Chenshuang, mother of a 4-year-old boy in Chongqing, spent 4,000 yuan on 40 online English tutoring sessions for her son, but soon regretted it.

"Such tutoring helps parents save time traveling, but kids are easily distracted when sitting in front of a laptop at home," Wang said.

Market players said some entrepreneurs had entered the children's education sector in the past five years as they were optimistic about the prospects, but an eagerness to cash in sometimes meant that quality was sacrificed.

Wang, who graduated from a foreign language university, said she now teaches her son English by talking to him in the language each day and by helping him read children's books. She also plans to send him to an overseas summer camp.

"We hope English will become a tool for him to connect with people from around the world as China's international profile continues to rise," she said.

"He will read more English-language books than I did, which will help him form a more diversified mindset and look at the world from different perspectives."

zhouwenting@chinadaily.com.cn

|

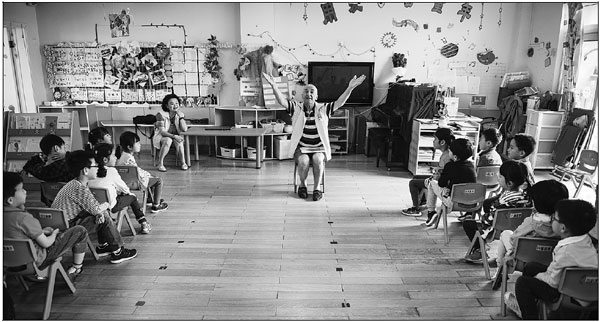

John Johnson, a retiree from the UK, teaches English for free at a kindergarten in Suzhou, Jiangsu province. Li Xiang / Xinhua |

|

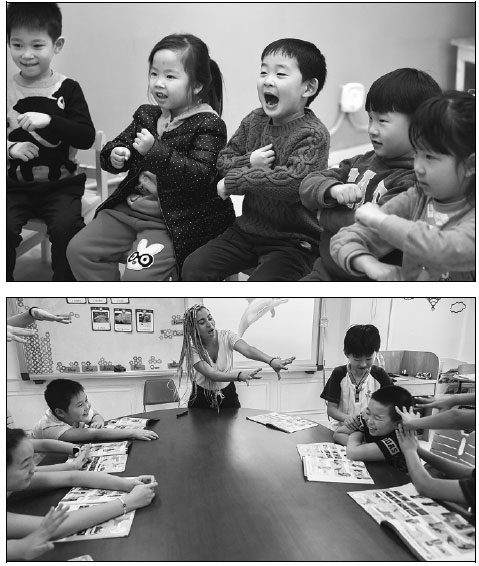

Top: Children learn English at a community center in the Yayuncun area of Beijing. Ju Huanzong / Xinhua A woman from South Africa teaches English at a primary school in Changxing county, Zhejiang province. Xu Yu / Xinhua |

(China Daily 01/24/2019 page2)