A place where beauty takes root

Visitors to London's Kew Gardens have been inspired by China's fascinating and colorful horticultural legacy, Earle Gale reports

When Kew Gardens reopened it s Great Pagoda in 2018, it was more than a return-to-form for one of Kew's top attractions, it was an acknowledgment of the important influence of China on British horticulture.

The 10-story Chinese-style structure , built in 1761, is a star attraction at the botanical repository in southwest London where more than 30,000 types of plant are protected and displayed and where 7 million floral samples are stored.

|

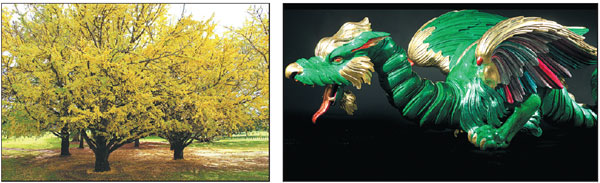

Ginkgo trees and decorative dragons are just some of the attractions on display at Kew Gardens in the British capital. Photos Provided to China Daily |

The pagoda had been a shadow of it s former self, ever since the 80 carved wooden dragons that originally adorned it rotted and were removed. Now, 230 years after their demise and thanks to a 5 million pound ($6.4 million) investment, they have been re-created in a long-lasting and light synthetic material, and the building, which has pride of place in the World Heritage Site garden, has been repainted and restored in a makeover that should last another 100 years.

Since the work wrapped up in July, visitors to Kew, which is officially called the Royal Botanic Gardens, are again making a beeline for the pagoda. It was the brainchild of William Chambers, who lived in China between 1745 and 1747 and who returned to the United Kingdom greatly impressed by what he saw. When it was finished, the pagoda, which was funded by Princess Augusta, the mother of Britain's King George III, was said to be the most authentic Chinese-style structure in Europe. But it was not the first. Kew also boasted an imagining of Confucius' home, a Chinese-style garden, and a pen full of Chinese pheasants. And there were other China-inspired gardens and buildings elsewhere in the UK.

Chambers was an early supporter o f the Chinese style of gardening, and a fierce critic of Capability Brown, the leading designer of English gardens at the time, who Chambers said was boring. Chambers wanted gardens to be full of surprises, like those he saw in China, and he urged Britons to adopt the Chinese techniques of concealment, asymmetry and naturalism.

Before Chambers, others had made similar observations. In fact, Chinese gardens had been gaining traction in the UK ever since the Venetian merchant and traveler Marco Polo became the first European to describe them in the 1200s after visiting the summer palace of Kublai Khan in today's Shangdu in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region. Polo also described the gardens of the imperial palace in today's Beijing and talked of pavilions, lakes, and a man-made hill covered with evergreen trees and green azurite stones.

Other early visitors to China had similar stories. Francis Xavier, a Jesuit priest who arrived in 1552, was inspired, as was another Jesuit, Matteo Ricci, who arrived in 1601.

The English statesman and essayist William Temple didn't set foot in China personally but read extensively about its gardens and wrote in 1685 about the beauty without order found in Chinese traditional gardens. He coined the word Sharawadgi, essentially a lack of rigid lines, to describe the concept and it caught on among English gardeners at the time.

In 1696, Louis Le Comte, mathematician to the king of France, published his memoirs after visiting China and described an exaggeration of nature, but not an attempt to defy it.

One of the first British attempts at mimicking these near-mythical Chinese gardens came in 1738 with the construction of a building and garden at Stowe House in the English county of Buckinghamshire. Lord Anson created gardens at Shugborough Hall in the county of Staffordshire in 1747 that included a Chinese-style house and bridge.

Jane Kilpatrick, an Oxford-educated freelance historian and garden writer, describes the early introduction of Chinese plants into the UK in two books:

Gifts from the Gardens of China: The Introduction of Traditional Chinese Garden Plants to Britain 1698-1862 and Fathers of Botany: The Discovery of Chinese Plants by European Missionaries.

Tony Kirkham, head of arboretum, gardens and horticulture services at Kew, said many of the 14,000 trees at the botanic gardens originated in China, including Britain's first maidenhair tree, or ginkgo, which was planted at Kew in 1762 after it was sourced by Princess Augusta, the person who funded the pagoda.

"She wanted the best collection in Europe, and she got her way," Kirkham said of the tree that still stands and is now 21 meters tall. The ginkgo is one of Kew's five "Old Lions" planted in the mid-18th century. Another, Styphnolobium japonicum or the pagoda tree, is 250 years old and is also from China.

Plants known and loved by British gardeners today that originated in China include peonies, gardenias, witch-hazels, azaleas, magnolias, ginkgos, camellias, rhododendrons, the golden larch, chrysanthemums, bamboo and ginseng.

Contact the writer at earle@mail.chinadailyuk.com

|

Plants known and loved by British gardeners today that originated in China include (from top) azaleas, chrysanthemums, rhododendrons, camellias, magnolias and lucky bamboo. |

|

An artist's depiction of the restored Great Pagoda at Kew Gardens in London. |

(China Daily 01/02/2019 page3)