Ending on a perfect note

|

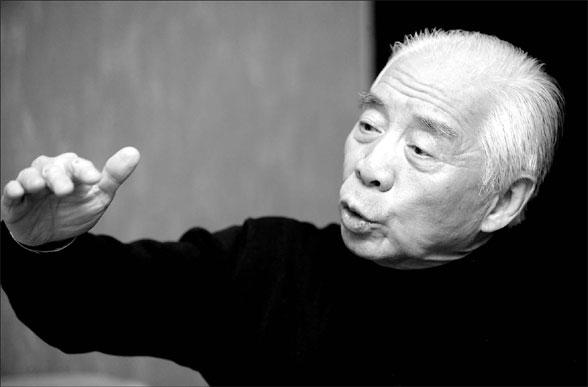

Composer Wu Zuqiang. Wu Zhiyi |

To counter the cultural clashes that have threatened China in the past and now hang, like an immense sword, over prospects for peace on Earth, composer Wu Zuqiang works for an expanding cultural tolerance and regards it as the foothold for China to embark on a cultural renaissance.

One of his actions was to push for the building of the National Grand Theater, or the National Center for Performing Art. At 81, he has worked on it for more than two decades. He believes that when people see more about the world's diverse cultures, they will be more tolerant of other people's ideas and ideals.

As the son of a prominent scholar, Wu knows more about the importance of culture and tolerance than many other people. His father Wu Ying (1891-1959), studied English literature at China's first foreign language institute in Wuhan, Central China's Hubei province, which was built by reformists of the Qing Dynasty (AD 1644-1911) in 1893.

When the last emperor of the Qing moved out of the Forbidden City in 1924, Wu Ying worked with other scholars to adapt the palace into a public museum, which opened one year later. In 1955, Wu Ying donated his family's entire collection of 241 ancient artworks to the museum, including bronzes, calligraphies, ceramics and paintings. "They are all in the category of national treasures," says Yang Xin, veteran researcher at the museum.

Born in 1927, in Beijing, Wu Zuqiang studied piano as a child. At 20, he joined the National Music Conservatory in Nanjing. After 1949, the conservatory moved to Beijing. He became a lecturer there after graduation in 1952, and a year later he was sent to Moscow.

At the celebration of the 40th anniversary of the 1917 Revolution in 1957, Mao Zedong arrived in Moscow, met the Chinese students and gave a speech, which was often quoted in the era.

"The world is yours and also ours, but in the end it is yours," said Mao. "The young people are filled with vitality, like the sun at eight or nine in the morning."

These words convinced Wu and other students that their knowledge would be "used everywhere" in the construction of New China.

When he returned to Beijing from Moscow, Wu had to work as a farmer for six months before he could put what he'd learned to use. He applied to compose music for a ballet celebrating the 10th birthday of the People's Republic of China. The assignment exempted him from three days' work in the fields each week. Given two desks in a classroom, he and Du Mingxin, also a lecturer at the conservatory, wrote the music for The Mermaid, or Yu Mei Ren, which was China's first ballet.

In 1964 he composed music for the ballet Red Detachment of Women. The music, which drew elements from Hainan Island folk music, was so successful that it is still highly regarded today.

But Wu did not receive any favor for the music. After Mao praised it in October 1964, his wife Jiang Qing decided to change it into a "model play". In her eyes, Wu, with his family and educational background, should not be the one credited. She assembled a team of composers and replaced Wu's ethnic music with revolutionary tunes.

While his best work was being changed, Wu taught students until the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) began in 1966 and he was forced into "re-education" by cleaning the campus. After different groups of the Red Guards began to fight each other in 1967, he was released, went home and focused on tailoring. He made clothes for dozens of people in art circles, and even one set of Mao Suits for himself.

He was not allowed to play music until 1972, when a friend invited him to join an office under the Ministry of Culture to criticize the former Soviet Union's "revisionism". Having more freedom, he penned the symphony Little Sisters on the Grassland. After the "cultural revolution" ended in 1976, he became vice president and later president of the conservatory, which re-opened after being closed for almost 10 years.

"I could not breathe the moment the gate to the campus was opened. Grasses were tall, buildings were dilapidated, desks, chairs, pianos and other musical instruments were gone. Professors could not be contacted and some died," he says.

When the national college entrance exam resumed in 1977, more than 11,000 people applied for the conservatory but it could only admit 100 students. The students had no place to stay and about 60 of them slept in the auditorium.

"But they all knew how precious a chance this could be, so they were very hardworking," says Wu.

Quite a number of them have since risen to international fame, such as composers Chen Yi, Hao Weiya, Tan Dun, Guo Wenjing, Ye Xiaogang, and Liu Suola.

|

Wu used to travel around the city by bicycle. Wang Wenlan |

He retired from the presidency at the conservatory in 1989 but still teaches there. Hao Weiya, who became Wu's student in 1989 and works now as a professor at the conservatory, was impressed when Wu reminded him not to try too hard to show a Chinese identity in his work. "In general, as long as you are Chinese, your work has Chinese elements. No one can surpass his ethnicity and era," Wu says.

Even on his busiest days, Wu never stopped in his efforts to have a national theater built. He first proposed it in the 1980s, when the State Council - China's cabinet - had a meeting with experts to talk about Beijing's application for hosting the 2000 Olympics. His proposal was considered, but no progress was made afterward.

As a member of the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) - the nation's top political advisory body - Wu proposed building a national theater at the annual session every year and always had dozens or even hundreds of other members co-sign on his proposal.

His chance came in the early 1990s, when the debt-ridden China National Orchestra, having failed to pay salaries for its musicians, considered accepting a 600,000 yuan ($80,000) sponsorship deal with a small enterprise in Hainan and putting the name of the latter before the "national".

The situation aroused the concern of state leaders about the survival of cultural organizations in the market economy, and when a meeting was called to discuss the issue, Wu again proposed building a national theater. This time he won the support of state leaders.

In the late 1990s, three possible designs for the center were chosen from the more than 40 submitted from all over the world. Out of the three, Wu favored the one by French architect Paul Andreu.

"There was also one that looked like the neighboring National Museum or Great Hall of the People, of a SU style, but we are in a new era. What I care most is whether a theater is convenient, and this one is the easiest to use for musicians."

Since construction of the national theater began in 2001, Wu has functioned as a channel between the project team and art and political circles.

"For me, it is my baby. I have worked on it for so many years and I am happy to see it in my 80s. In a way, what it symbolizes - a welcoming gesture to different cultures - happens to be what I have yearned for, especially in the most difficult days."

(China Daily 01/29/2008 page20)