Smashing science fictions

|

|

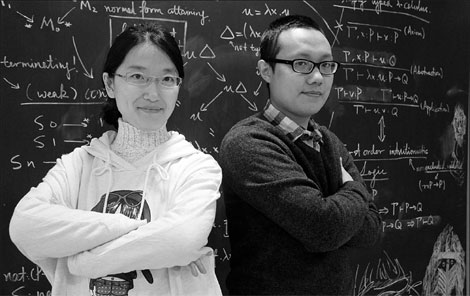

'Miss Myth Smasher' Yuan Xinting (left) poses with Xu Lai, editor-in-chief of Guokr.com. Photos by Wang Ru / China Daily |

Meet Ms Myth Smasher, who has become a popular Internet icon in the country for using evidence to dispel widely believed falsehoods. Wang Ru reports.

Will washing down prawns with orange juice cause deadly arsenic to form in your stomach? Were the recent videos of UFOs zipping over China real? Do civilian aircraft stock specialized parachutes just for the captains? In the era when online social networks and micro blogs are propelling public belief in scientific falsehoods, one woman is stepping up to put down false facts and verify outlandish truths.

Meet "Miss Myth Smasher", Yuan Xinting. The woman with a PhD in organic chemistry from the University of Illinois has become an Internet sensation in China for her work refuting or verifying widely held - but usually untrue - beliefs about scientific affairs.

Her posts on Guokr.com - a science website with more than 200,000 registered members - have become wildly popular. More than 160,000 fans follow Yuan on her Sina Weibo micro blog, which is China's version of Twitter.

Her fame was ignited by an interview with China Central Television in which she dispelled the "super moon" theory circulating online.

A myth had erupted on the Chinese Internet that Japan's March 11 earthquake was caused by the moon's closer-than-usual proximity to Earth.

On March 19, the moon orbited closer to our planet than it had in 18 years, at one point coming within 356,577 kilometers of us. Panic proliferated on the Chinese Internet, when one astronomer said this had caused Japan's temblor, despite scientists' and foreign media's reports countering the claim.

Yuan and her colleagues restored calm by collecting figures and studies that disproved the "super moon" hypothesis. She also presented an influential diagram tracking the relationship - actually, the lack thereof - between the moon's distance from our planet and earthquakes of at least 6.5-magnitude.

"Scientific research and myth evaluation are similar," Yuan says. "Both entice us to pose a question and methodically answer it. Before, I did my own research in a lab. Now, I research other scientists' findings online."

The job's greatest challenge, she says, is defining myths as such.

"For instance, the taboos surrounding zuoyuezi - the widely accepted beliefs about women's health during the first month after childbirth - forbids new mothers from being near open windows or showering," Yuan says.

"It may have made sense in the old days, when living conditions and sanitation were much worse. But the traditions don't fit today's realities."

China is far from alone in its embrace of untrue beliefs.

"Every culture has science myths, and many are similar," she says.

She points to the idea that mixing vitamin C with seafood can kill you.

Most Chinese hold it's poisonous to eat crab and persimmon in one sitting, while many in Western countries say the same of citrus and shrimp.

"Only massive amounts of these combinations create arsenic," she says.

"You would die from eating too much long before you were poisoned."

Yuan says her work is inspired by the Discovery Channel's acclaimed TV show MythBusters.

"Americans are also frightened by various myths," she says.

"But they have more extensive channels to better understand the facts and a more advanced popular science environment."

Guokr.com's editor-in-chief Xu Lai believes, "Popular science has been marginalized in Chinese society. Ordinary people have only started to again pay attention to science in recent years, mostly because of such concerns as food safety and environmental pollution."

The 2010 survey of scientific literacy conducted by the China Association for Science and Technology (CAST) finds China's 3.27-percent score equals that of developed countries' in the 1990s.

China's government has been emphasizing the importance of science and technology to economic growth.

The national R&D budget has increased by an average of 21 percent a year for the past decade. In 2010, 706 billion yuan ($110 billion) was earmarked for R&D - 21.7 percent more than the year before.

The growing investment has reaped impressive results, including a space walk in 2009.

But popular science hasn't kept pace. Most magazines dedicated to the subject haven't survived the market economy.

"The Web is the ideal platform for popular science, because it updates so rapidly and is interactive. We hope Guokr.com's channels can captivate more young people's interest."

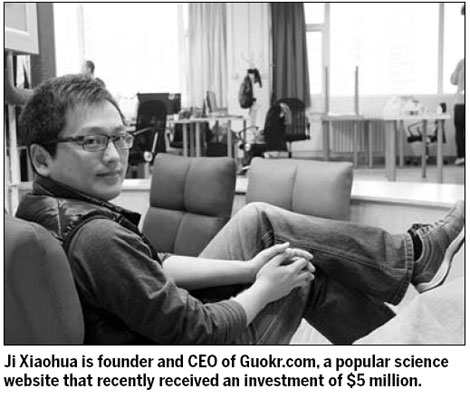

Biologist, popular science journalist and head of the science-blogging NGO Squirrels Group Ji Xiaohua founded the website in November. The company employs a team of 70, including 20 scientists-turned-editors.

"Guoker.com is ... a social network service for people interested in science and technology," Ji explains.

"Aside from education and propaganda, the only way to make science popular is to make it interesting. That's what we do."