Living like a local

|

|

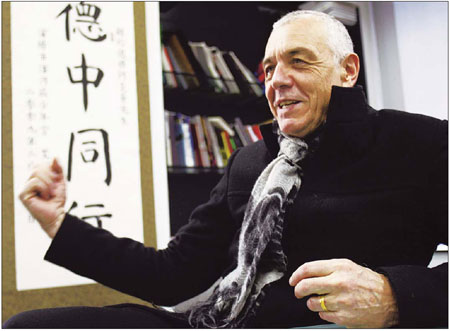

Michael Kahn-Ackermann sees the founding of Goethe-Institute China in Beijing as the proudest achievement of his career. Zhang Wei / China Daily |

The 'benefit of misunderstanding ' has left the founder of Goethe-Institute China with a strong affection for the country he has called home on and off for the past 20 years. Yang Guang reports

German Michael Kahn-Ackermann is in many ways a Chinese: he speaks Mandarin, reads The Analects, translates Chinese literature, sips Pu'er tea, and even jokes like a local. Founder and first director of Goethe-Institute China, the German educational and cultural institution for expanding Sino-German cultural exchange and cooperation, Ackermann, 62, has lived in China on and off for almost 20 years.

The once angry young man from a small village in Bavaria first arrived in China in 1975 to study Chinese history at Peking University.

His two-year stint in China at the end of the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) saw him in an indifferent and suspicious social milieu, and subject to the empty verbiage of classes.

"Despite my disappointment, it was a significant experience that reshaped my world view," he says.

After going back to Germany, Ackermann was invited to give a talk on radio about his days in China. He later produced a book, Inside China Outside Doors, based on the talk, which was an instant success.

But to this day Ackermann doesn't feel he is "inside doors". "I am sitting on the threshold," he says. That position, he says, gives him a Western perspective on China and allows him to retain his curiosity.

He returned to China in 1982, teaching German at Tongji University, Shanghai, till 1985. It was then that he began to translate Chinese literature. His translation of Zhang Jie's Leaden Wings remains the most well-known Chinese novel among German readers.

Ackermann proposed the idea of the "benefit of misunderstanding", at a seminar on contemporary Chinese literature in 1986. Between the two types of misunderstanding - the stereotypical and the creative - he says the latter is not detrimental. "China's assimilation of Western culture is mostly a process of misunderstanding, and vice versa."

According to Ackermann, European readers' interest in Chinese literature can be traced to their curiosity about China, rather than an interest in literature per se. He explains that the attention Latin American literature draws in Europe can be attributed to a constellation of writers such as Argentinean Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) and Colombian Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

"China still lacks such names," he says.

Ackermann sees the founding of Goethe-Institute China in Beijing as the proudest achievement of his career.

In 1984, former German chancellor Helmut Kohl was on a state visit to China and talked to Deng Xiaoping (1904-97) about establishing the institute in China. No foreign cultural exchange institution was allowed at that time. An arduous three-year negotiation ensued to make the institute an exception in 1988.

Ackermann was transferred in 1994 to work in East Europe and Italy, before returning to China in 2006.

It was during his second stint here that Ackermann directed the Germany and China - Moving Ahead Together program, the biggest such event that Germany has ever organized abroad.

Developed around the theme of sustainable urban development, the three-year program, launched in 2007, has moved around five Chinese regional centers - Nanjing, Chongqing, Guangzhou, Shenyang and Wuhan - culminating in the German-Chinese House at the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai.

He says the program, that promoted Germany in all its cultural, economic, scientific and social diversity, has become a paradigm for the country's building of soft power. Germany will launch a similar program in India in 2011, based on the successful experience in China.

Ackermann has decided to stay in China, after his retirement in 2011. He is currently busy preparing for an 18-month exhibition, which will kick off in March at the National Museum of China, in cooperation with the three largest museums in Germany, on life and art in the Age of Enlightenment.

He cites German poet Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) to express his feelings toward China. While the poet was once repudiated for his criticism of his motherland, he says his criticism comes out of love.

"I feel I can criticize China now, because I love the country," Ackermann says.