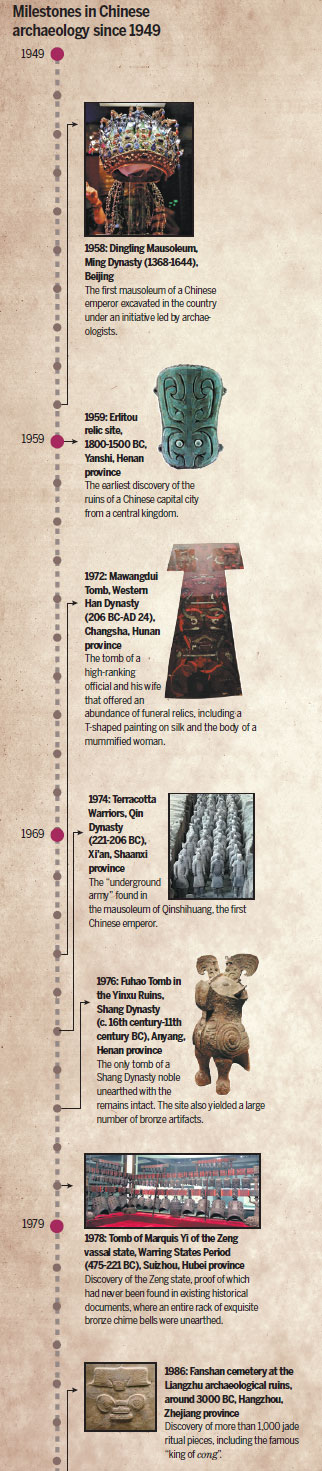

Landmark discoveries

Chinese archaeology still relies on the dedication of its practitioners despite the advances made over the past decades, Wang Kaihao reports.

In 1957, 20-year-old Li Boqian, a sophomore undergraduate at the school of history at Peking University, had to choose a specific direction for his studies. Hearing that archaeologists have the chance to travel a lot, Li thought it would be fun to pick that subject.

Yet, he did not expect to be glued to it for a lifetime.

"It became my destiny," the 82-year-old tells China Daily. "Much emphasis was placed on archaeology even in the early years of New China when the country was still enduring tough times. Because of that, everyone (in archaeological circles) was eager to make a contribution using the knowledge they had gained at university."

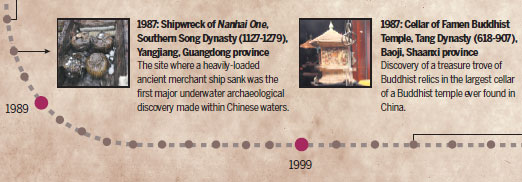

Halted by the civil war, Chinese archaeology resumed shortly after the founding of New China in 1949. In 1950, the country's first archaeological excavation took place in Huixian county, Central China's Henan province.

"It just took around 10 people - that was how everything got started,"Li recalls.

In 1952, Peking University became the first Chinese educational institution to nurture students of archaeology major.

Chen Xingcan, head of Institute of Archaeology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, says majors in archaeology and cultural heritage conservation are now offered by over 100 Chinese universities. Currently, more than 60 institutions and 2,000 individuals in China hold licenses to lead archaeological excavations.

Over the years, the team continued to build their experience - and muscles - as they tried to keep pace with the country's rapid economic development.

"Large-scale urbanization and the construction of infrastructure from the 1990s presented new challenges in terms of the conservation of heritage sites," Chen says. "The demand for archaeological research increased, and brought us many new opportunities."

China's cultural relic protection laws stipulate that archaeological investigation must be undertaken before construction can begin on any new major infrastructure project.

During the early 1980s, about 100 archaeological surveys were undertaken every year, and this number has risen to nearly 1,000 now, according to Wang Wei, director of the Society of Chinese Archaeology.

Legend to history

In 1928, the discovery of the Yinxu Ruins, the remains of a capital city that existed during the latter part of the Shang Dynasty (c.16th century-11th century BC) in Henan, lifted a shroud that hung over Chinese archaeology and also helped the Shang Dynasty to emerge from legend into actual history due to the abundant findings of oracle bones - China's earliest known form of written characters.

"Unlike many other ancient civilizations, China had a particular tradition of keeping detailed records of history throughout ancient times," Li says.

Records of the Grand Historian, or Shiji, compiled by Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24) historian Sima Qian, remains a monumental reference work for archaeological studies.

According to the book, the Xia Dynasty (c. 21st century-16th century BC), the first central kingdom with a vast land in China, once set its capital in an area around today's Luoyang in Henan. Following this clue, archaeologists located the Erlitou relic site in Luoyang in 1959. As the biggest capital city ruins of its time in East Asia, it is widely considered in Chinese academia as the location of the Xia capital, according to Wang.

"However, old theories also once led people to form stereotypical views that the origins of Chinese civilization must lie in the Central China Plain," Li says.

Nevertheless, a boom in the number of discoveries indicating early-stage civilizations over the following decades have gradually changed archaeologists' minds. Ranging from the western bank of Liaohe River in Northeast China, throughout Central China to the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, these findings appeared like stars on a clear night all across the country.

Many brilliant discoveries unknown to history were revealed by the shovels of the archaeologists there.

For example, the 5,300-year-old archaeological ruins of Liangzhu city in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, famed for its gradual discovery of outstanding ceremonial jade pieces, the palatial city of a regional state, and a complex dam system - thought to be the world's earliest - became China's latest entries on the list of UNESCO World Heritage sites in July, signifying global recognition for the 5,000-year Chinese civilization, according to Liu Bin, director of the Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology.

"We began to realize that Chinese civilization formed in unison, yet with diversity," Wang from the Society of Chinese Archaeology says."About 5,000 years ago, hierarchical societies and metropolises began to mushroom all over today's China. Central China rose in prominence as a hub for civilization about 4,500 years ago - absorbing different cultural elements, mixing them together and later influencing a much wider region."

Power of new technology

Archaeology is not only about social science. Radiocarbon dating, a technology used to measure the age of artifacts unearthed at archaeological sites - which, according to Li, has an accuracy deviation of no more than 5 percent - began to be widely used in China in the 1990s.

However, methods in natural science have since gone far beyond.

"Research discoveries pertaining to plants, animals, the natural environment, climate change and many other fields in the natural sciences, are widely employed by archaeologists," Song Xinchao, deputy director of the National Cultural Heritage Administration, says. "That means when you farm the same area of a field, your yield can greatly improve, and details can be scrutinized in a hi-tech lab, which has better conditions for conservation."

Chen explains that orthodox historical records from ancient China mostly cover dynastic politics, so the information gleaned by leveraging the natural sciences can help people today to more comprehensively understand society in the past.

"We used to focus on unearthed objects," he says."But now we look at the bigger picture to evaluate human settlements."

In Liangzhu, for instance, Liu's team is researching unearthed plant seeds and animal bones in a lab in a bid to uncover the dietary habits of people in the area 5,000 years ago. He also wants to find out how such a brilliant civilization disappeared 4,300 years ago. Research focusing on soil and hydrological environment may unveil evidence of a prehistoric flood.

Developments and techniques being used in land-based research on human settlements is being employed in other archaeological arenas in China, sometimes in a way that has not been seen elsewhere in the world. In 2007, a special water tank was used to salvage Nanhai One - a Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279) shipwreck off the coast of Guangdong province - in order to move it to a museum laboratory for excavation from the mud and sand.

"Nowadays, archaeology students at Peking University have so much more to learn than we did," Li says, smiling. "However, no matter how many hi-tech methods are used in labs, fieldwork remains the foundation. An archaeologist still has to start by learning how to use a spade."

A global perspective

Modern archaeology was introduced in China in the 1920s by Johan Gunnar Andersson, a Swedish geologist and archaeologist. He discovered Yangshao Neolithic Culture in Henan in 1921.

Some of the earliest Chinese archaeologists were trained overseas. For example, Xia Nai, the founder of archaeology in New China, got his PhD in Egyptology from the University of London.

"They always had a dream to lead archaeological teams to better see the world," Chen recalls.

Chen says following China's reform and opening-up in the 1980s, cross-border academic exchanges in the field of archaeology has been frequent, and the past decade has witnessed many Chinese archaeologists realizing their predecessors' dream conducting research on foreign land.

Chinese archaeologists are currently overseeing excavations in more than 30 countries around the world.

"Some programs will help our own research back here in China, as we share the trade routes, like the Silk Road," Chen says. "From ancient Egypt and Maya civilization, which seem less connected to us, we can still learn a great deal through comparative studies about early-stage civilizations."

He continues: "If we want to understand the unique features of Chinese civilization, we have to know what the characteristics of others are."

Chen says it was almost a blank in China to explore the concept of prehistoric communication between China, West Asia and Europe. But greater inclusiveness has been nurtured in recent years, as mutual learning about different civilizations is known to be essential for modern world's understanding of the past, he says.

"There is the booming scenario of ancient people and societies from across the Eurasian landmass learning from each other before written recordings existed," Chen says."Going abroad to conduct research enables us to learn more about it."

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily Global 09/19/2019 page14)