A disciple's lot: laying stones along a very long road

Often departing from the beaten track in remote parts of China, a photographer evokes the refinement of Chinese paintings and of nature itself

Michael Cherney loves taking pictures of mountains. And he loves taking those pictures the way they were painted by ancient Chinese landscape artists centuries or millennia ago.

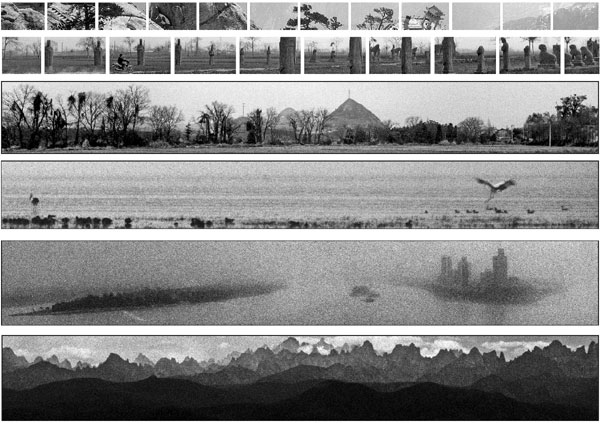

One frame, a narrow strip of rolling hills taken on the plateaus of northwestern China, is dominated by the interplay between black and white and the multiple shades of gray in between. A meandering, monochrome composition, it is evocative of those ancient Chinese works in which ink was applied to paper in a few sweeping strokes to maximize the sense of grandeur.

|

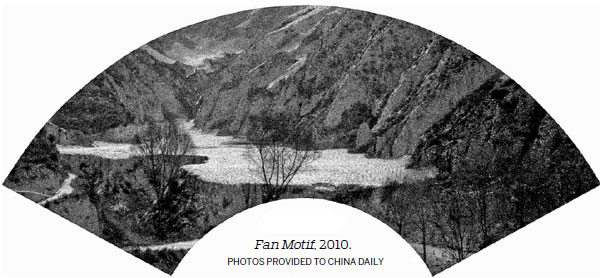

From top: Mount Hua Album from the Bounded By Mountains series, 2005; Northern Song Spirit Road from the Bounded By Mountains series, 2005; Level Trees, Distant Mountains series, 2009; part of Twilight Cranes, 2007; part of Ten Thousand Li of the Yangtze River series, 2012; Cherney's Map of Mountains and Seas, 2012 is dominated by the interplay of black and white and the multiple grays in between. Photos Provided to China Daily |

And it's not just the wide-angled pictures. Close-up shots of wrinkled mountain ridges fill the entire frame in one view from his Yi Mountain Passages series. The rugged texture of the land has often been created by dragging a dry brush across the paper, and by dabbing a few dots of ink here and there.

Then there are the trees on the mountains. In his Level Trees, Distant Mountains series, wintry branches are fully revealed against the dusky sky. Such austerity recalls the equally frugal depictions of trees often found in landscapes from the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), which Cherney adored for having embraced "reductionism" in art.

The American Jewish artist believes that by focusing his lens on nature he has found a way of aligning himself with "an aesthetic that's most beautifully and uniquely Chinese" without taking up a brush.

"Ancient Chinese landscape painters extracted their whole vocabulary from nature," he says, pointing to the various effects their inky brush made on the absorbent rice paper, effects intended to depict everything from a dripping, misty riverside scene to a gnarled tree and a wind-whipped rock.

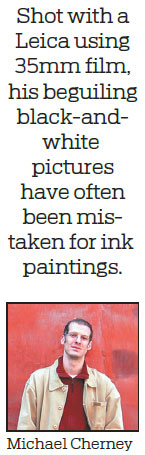

Shot with a Leica using 35 mm film, his beguiling black-and-white pictures have often been mistaken for ink paintings.

Yet from the day photography was born in the mid-19th century it was thought that it would replace painting - landscapes and portraits in particular - rather than reconjuring its magic.

"In the West, photography was viewed with great suspicion by painters who feared that the new invention might render their old art obsolete," says Cherney, pointing to the Hudson River School painters who romanticized the American landscape by capturing it at its most sublime.

This often included, among others, a stormy sky and an equally tempestuous sea, both reflective of the drama of light.

"To seize the fleeting moment - this was exactly what photography was invented to do," he says. "However, with traditional Chinese landscape painting the intention was completely different."

The Chinese were less preoccupied with the faithful recording of what they saw than with the expression of feelings these views had aroused inside them, he says. In doing so they were assisted by the brushworks they had "borrowed" from nature and kept refining.

"It's about capturing the essential rather than the ephemeral, the transcendental rather than the transient," says Cherney, who over the past 20 years has traveled all over China in search of scenery that overlaps with his mind's rubbing of those age-old traces of ink.

Google Maps and GPS facilitate the preparation, but help from locals has been critical once he is out in the wild.

"When I was photographing the Three Gorges as part of my Ten Thousand Li of the Yangtze River series (one li is equivalent to 0.5 kilometers), a local farmer who has lived his entire life atop the peak overlooking one of the gorges cut a path for us with his machete, through the last several hundred meters of foliage to a rocky outcropping. It was directly above the gorge, somewhere he himself hadn't visited in quite a number of years."

Not all surprises were pleasant ones: what appears in an ancient scroll as a mighty, mist-wreathed mountain may in reality just be a hillock.

Another time, Cherney traveled a long distance to the warm-weathered southeastern China, having seen a Yuan Dynasty masterpiece depicting a swath of water and the corrugated, tree-interspersed mountains along its bank. What he found, instead, was a lush green that carpeted the entire landscape. (Another example of the ancient Chinese landscape artists' tendency to paint as much from imagination as from observation.)

Despite his infatuation with the painted surface, Cherney has long gone well beneath it.

"Mine is an art-history approach. In the West people go to national parks, the Grand Canyon, for example, to see magnificent landscapes as undisturbed nature. In China, as you scale the fabled mountains you are confronted not only with natural beauty, but also ancient works of calligraphy chiseled on cliffs. This makes you ever aware of the fact that you are traveling on the same path that has been traveled by those who have come before. My work is about putting one stone on a very long road."

This means to steep oneself in the country's literary tradition, to soak in the nuances, to let the mood sink in, and ultimately to journey to whatever place had been a stage to the drama of history, real or imaginary. It could also mean the quest for a visual equivalent to a beautiful line that sends the artist's heart aquiver.

Amid his sequence of photographs taken of the ancient path leading to a 12th-century emperor's burial ground in central China is one shot that features a motorcyclist. Whooshing into the frame from its left side, under the silent gaze of the tomb guards, the man and his mount constitute a worldly contrast to the site's other-worldly solemnity.

The pictures are mounted in the traditional Chinese format of an accordion fold album, and can thus be viewed one leaf at a time.

"The rhythm of viewing is suddenly interrupted when one arrives at this particular frame," Cherney says.

It will pick up with the next frame, but a jarring note has been dropped into the requiem of history.

A similar contrast occurred when Cherney, photographing in a Buddhist cave-dotted area in southwestern China, was led by a local cultural official into a common household nestled at the foot of a mountain. Through the front door and the living quarters, Cherney found himself standing in the middle of the family kitchen staring into a millennium-old stone carving on the rocky mountain slope that served as the kitchen's back wall.

"There it was, a carved Buddha presiding over a retinue of seasoning bottles placed horizontally on a shelf along the stone wall, face blackened by cooking," Cherney says. "My company told me that this was probably the best way to protect the carving without spending money - no one would run into another person's home and cut the Buddha's head off."

One of his most thoughtful bodies of work is of cranes in their endangered homeland in Poyang Lake in southern China. Cherney is equally inspired by a 17th-century Japanese painting and an ancient stone-carved piece of Chinese calligraphy, with deep cracks across the stele vaguely resembling birds spreading their wings.

And vague could be said of the elegant images, an effect achieved by excessive enlargement.

"The loss of detail is meant to invite interpretation from the viewer," says Cherney, who practices Chinese calligraphy himself.

"In this case it adds resonance: the original writing is the author's lamentation on the death of his crane, while mine is a pictorial epitaph to a divine creature that is losing their habitat."

Cherney's work "is done with the great sophistication that draws on the subtleties of China's most scholarly and esoteric traditions", said Jerome Silbergeld, professor of Chinese art history at Princeton University, where Cherney's works have gone on display.

In 2016 Cherney encountered a book titled The River, the Plain and the State. Written by Ling Zhang, history professor at Boston College, the book chronicles the flooding of the Yellow River, China's second-longest and one closely linked to the birth of Chinese civilization, during the country's Northern Song Dynasty between 1048 and 1128.

Intrigued, Cherney contacted the author, collected more information and read maps ancient and modern before starting work on what is known as his River Schema series. Photographing extensively along the river's middle reaches covering 1,200 kilometers, Cherney waded into the river of history long after the physical river had changed course, been tamed, or, in certain sections, dried up.

"Some areas once inundated are a great distance from where the river flows now, " Cherney says. "In addition to historical site, I also photographed locations that are of importance today, such as where the South-North Water Transfer Project intersects with the river," he says, referring to the controversial project aimed at diverting huge quantities of water from the Yangtze River, China's longest, in the south to Yellow River Basin in the arid north.

"I position my works somewhere between a poem and a document," he says.

While he has often worked "hard to crop away evidence of the present day to convey a sense of expansive nature", he has, on an equal number of occasions, chosen to retain vestiges of human activity within the unfurling wildness.

His Ten Thousand Li of the Yangtze River series, comprised of 42 pictures taken over five years, is a case in point. Standing in the small islet in the middle of the river is not a smattering of trees but densely packed skyscrapers. Yet with their sharp contour softened by the all-enveloping mist, the buildings seem to have merged with their surroundings, receding slowly into the background. Soon they will become history.

Here and there one discovers a half-built bridge, a giant mining pit interspersed with modern machinery, or a couple of dozen sand-drudging boats that lie idling on the quiet river the same way a raft might have done a few centuries back. The cacophony is toned down by the muted palette of black and white.

"I love to photograph places that have accumulated a great deal of history - my strongest works combine history's grandeur with an aesthetic that supports it," Cherney says. "Meanwhile I would also like to see evidence of something happening now, something that defines this particular moment in the continuum of history. This imbues my photographs with meaning."

The search for that meaning has been eventful.

In 1991 Cherney graduated from the State University of New York at Binghamton with an East Asian history and language major. The next year he went to Beijing to study Chinese. "Soon after I was diagnosed with cancer and had to come back to the US for treatment. When I was cured and went back to China two years later I felt like I was going through a rebirth. And I wanted to really appreciate and observe life around me."

And observing life through a viewfinder seemed a natural choice, since around that time Cherney rediscovered the works of his late maternal grandfather, a photographer for the New York Daily News best known for his dramatically lit sports pictures.

One group of Cherney's earliest works involves a trip to a remote corner in Sichuan province in southwestern China, where the country's "last pony-express rider delivering mail on horseback to eight villages on round trips that took half a month to complete".

"The mountain was so steep and the rain so heavy that any road was washed away not long after it had been built. Today I still have the postal bag a rider gave me as a memento."

That experience culminated in a photo essay that was published in the Canadian travel magazine Outpost. "Usually there was an editor's note at the end of an essay telling readers how to get there. But with mine, the editor just dropped a line which effectively said: 'Don't bother!'"

In retrospect, the adventurous streak has always been there. But the narrative style has changed completely.

Each time after returning from his photographic travels and having the film developed, Cherney searched the film frame for qi (a Chinese term meaning spirit or energy). Qi is not the type of energy that animates a group of dancers, but one that invigorates the brushstrokes, painted or written.

This is usually separated from the clicking of the shutter by weeks or even months.

"Most Chinese painters did not do plein-air painting," Cherney says.

"After extensive travel they returned home to paint from memory. I choose whatever has stayed with me."

That memory is printed on Chinese rice paper and then mounted.

"The picture comes alive when the white comes through from behind," says Cherney, referring to the age-old Chinese practice of putting an extra layer of white paper at the back of the flimsy painting. He never digitally alters his photographs because they are "nature's gifts".

Most of Cherney's works are severely cropped, leaving a long horizontal slice that sometimes runs the visual gamut from dense to spartan. The inspiration comes from a hand scroll, which the artist deems emblematic of the Chinese way of seeing and storytelling.

"For centuries in the West, landscape painting has followed rules of fixed perspective. Instead of committing themselves to a linear perspective, ancient Chinese artists invite their viewers for a journey through a scroll, with changing views and shifting perspectives."

So the best way to appreciate a Cherney is to do what a member of the literati in ancient China did: to retreat to one's private chamber and have the scroll in hand revealed, bit by bit.

"What he's doing has enabled him to discover the literati deep inside himself," says Huang Dong, Cherney's Chinese wife of 26 years. The two first met on a train to the Great Wall in Beijing.

"I was then a student at Beijing Language and Culture University considering following in the footsteps of my father, a businessman who traded between the US and Asia," Cherney says. "These days my father often says, 'I don't quite understand what my son does exactly, but I'm proud of him.'"

At the end of each trip he returns home to Beijing, where the 50-year-old can hop into a taxi and give any young driver an education of the city's evolution over the past 30 years.

Cultural identity, art history, environmental commentary - Cherney's works are so topical that museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, have become his No 1 collectors.

Silbergeld, the Princeton professor, referring to Cherney using his Chinese name, says: "Qiu Mai's work is the cutting-edge demonstration of artistic globalization: if Asian artists can so readily 'come west', then what is it to prevent large numbers of future Western artists from 'going Asia'?"

Cherney's Chinese name means wheat in the autumn. For Chinese, wheat, bent under the weight of its ripened ears, is a symbol of humility. Humbled by "an artistic legacy under which one might teeter", as Cherney puts it, he nevertheless approaches the task with reverence and gusto.

And it is no coincidence that the Chinese saying he cherishes most comes from the mouth of a 14th-century painter-poet, talking about the journey of an artist, inside and out:

"I am a disciple of my mind, my mind of my eye, and my eye of the mountain."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

|

From left: Michael Cherney travels all over China taking pictures of landscapes that remind him of the painted brushstrokes from centuries ago; Cherney's photographic works on display during a 2018 exhibition at Three Shadows Photography Art Center in Beijing; Cherney's sequence of photographs are often mounted as accordion fold albums; Cherney uses his camera to convey a quintessential Chinese aesthetic. |

(China Daily Global 09/09/2019 page14)