Trade talks can't solve America's twin deficits

The trade war truce agreed upon by President Xi Jinping and President Trump at the G20 Osaka summit is very good news for the economies of both countries. Highly disruptive breaks in supply networks and in established trading patterns will be avoided. Everyone from soybean farmers to high-tech companies can breathe a tentative sigh of relief.

But it is important to realize that no possible trade agreement can reduce the overall trade deficit of the US, which stood at $879 billion in 2018, or any other nation. A country's trade deficit is not determined by exchange rates or by tariffs. Instead, it is determined primarily by the domestic savings and investment rates within the country itself.

The US faces a coming crisis in its twin deficits - large and growing government budget deficits and trade deficits. Both are caused by a lack of savings.

I taught macroeconomics in a graduate-level executive management program for 17 years. My students, who were all experienced managers aged 40 to 50, found this hard to understand, or even believe. They would ask: "What's the connection between savings rates and trade deficits? Explain this again."

It's straightforward.

Americans don't save enough to pay for both the country's investment and the government budget deficit.

So, the only possible source of additional funds is from foreigners.

If a country saves less than it invests, then foreigners have to make up the difference. Written as an equation: savings minus investment equals exports minus imports.

For example, the US saves less than it invests, so it must import more than it exports. That is, it must run a trade deficit. This must be financed by some country, substantially China, that saves more than it invests and thus runs a trade surplus.

Foreigners don't send goods to America for free. They are, in fact, making a loan to the US. So, a trade must be balanced by an equal and opposite transfer of financial assets from Americans to foreigners. In practice, these assets are mostly US government debt - US Treasury bills.

Government spending is a form of consumption, so government budget deficits reduce the overall savings rate. Last month, the US Congressional Budget office released its annual long-term budget outlook projections. The conclusions, while expected, are still frightening.

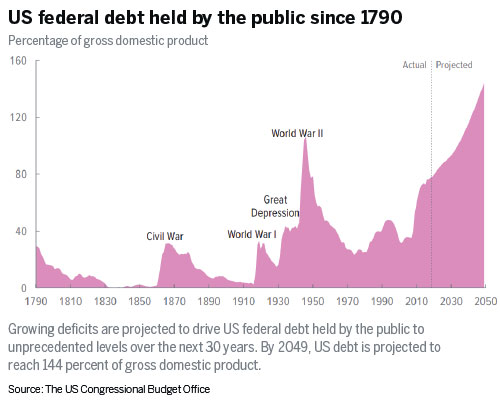

The current US government debt held by the public is $16.2 trillion, about 80 percent of GDP(which was $20.5 trillion in 2018), only slightly less than the level built up to fund World War II.

The CBO estimates that this will steadily rise to 144 percent of GDP by 2049 - an unprecedented level, even in wartime.

The rise in government debt is caused by an aging population that demands more government support plus rising medical care prices.

The US is certainly not alone in running large government deficits. Many European countries are in similar or worse positions. And, Japanese government deficits are much larger.

The US is, however, unusual in that it is able to get foreigners to finance a substantial portion of its deficit. In total, foreign investors and governments finance almost half of the US government debt. As explained above, this financing is just the mirror image of trade surpluses these countries run with the US.

This might sound like a good deal for the US. It does stimulate the economy in the short term. But, in the long term, it just allows American individuals to consume and the US government to spend without making hard choices.

Former French president Valery Giscard D'Estaing described the international role of the US dollar as creating "exorbitant privilege "for the US. But I think it has created an extraordinary danger for the US by allowing the country to run "twin deficits" in its government budget and trade accounts for much longer than would have been possible for any other country.

Herbert Stein, the chairman of the President's Council of Economic Advisors under president Nixon, famously stated Stein's Law, which says: "If something cannot go on forever, it will stop."

Stein was already writing about the then-new twin deficits in the early 1970s. Nobody then expected them to continue getting bigger and bigger for 50 years. Yet, there are good reasons to believe that they can't continue much longer.

At some point, foreign economies will change so that they can no longer fund US deficits.

We already see fundamental changes. China's extremely high savings rates have come down and its consumption rates are going up. So, China will have progressively smaller trade surpluses. Japan is already running trade deficits. So, the two largest lenders will not be available.

At the moment, the US economy looks great. Unemployment rates are very low. Famously, the unemployment rate for minorities is the lowest in history. The stock market is booming and growth is good.

But Stein's Law applies here. At some point in the near future, the US will have to make hard choices about how to solve the twin-deficit problem.

What are the options? The investment rate could go down - but that would slow future growth and technology development. The savings rate could go up - but we have no idea how to accomplish this. Taxes could go up - but this would probably lead to a decrease in private savings, a drop in stock values, and a rise in unemployment. Government spending could go down - but this is unlikely since aging people are demanding more government payments.

As hard as these choices are, some combination of them will have to be implemented sometime in the next decade. Personally, I'm afraid the crisis will hit just at the time when I need to begin receiving social security retirement payments and withdrawing funds from my stock portfolio.

And, the CBO says there are downside risks that could make the budget deficit much worse.

A big risk is that the interest rate paid on US Treasury bills, which has been at historic lows since about the year 2000, will go up sharply. If the rate rose to 5 percent, closer to the historic norm, the budget situation would quickly deteriorate.

Former Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke said in 2004 the world is in a "savings glut", which keeps the interest rate down. But, a large part of the population in many countries is getting ready to retire, so the international savings rate will go down, driving up interest rates.

Also, for a long time, there have not been many promising things to invest in - but, the new technologies related to artificial intelligence, 5G, robotics, and the internet of things will require lots of investment over the next 10 years, so the real demand for capital will go up. Again, this will likely drive up interest rates.

A comprehensive trade agreement between the US and China will be very good for both economies. And, a harmonious relationship between the two countries is important for the future of the world.

But fundamental economic problems facing the US and other countries are not caused by international trade deficits. The US has hard choices to make about its domestic economic policy that can't be dodged for long.

(China Daily Global 07/08/2019 page9)