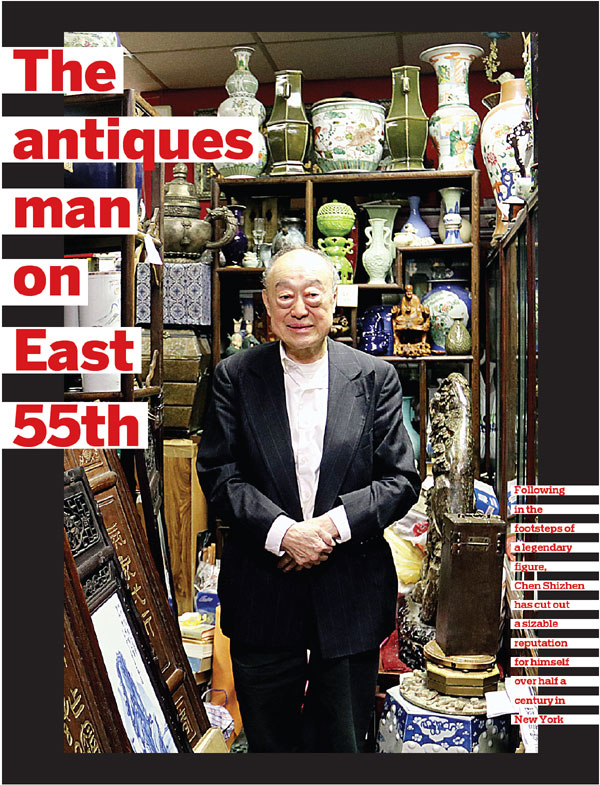

The antiques man on East 55th

Following in the footsteps of a legendary figure, Chen Shizhen has cut out a sizable reputation for himself over half a century in New York

On a weekend morning in 1964, Chen Shiz-hen, 28, looked down from an eighth-floor window of the Ton Ying Company on East 57th Street in Manhattan and saw a familiar limousine parked in front of the building.

"That car belonged to John D. Rockefeller III, who came in almost every weekend to look for 'Chinese toys', as he would call those pieces of antique," Chen, now 83, says.

"The place where our company used to sit, just opposite Tiffany's, has long been overtaken by another luxury brand if not Chanel," he said, surveying his congested antique gallery, tucked in a corner in the Manhattan Art& Antique Center, two floors below street level. Porcelain vases, big and small, together with dismantled wooden screens, inscribed or mounted with jade and precious stones, block the door.

"We used to have a different approach - what they call the Madison Avenue approach, where a few select antique pieces were displayed proudly in glass cases and didn't have to rub shoulders with one another," he says, referring to the old company's location at No 5 East 57th Street, between Madison Avenue and Fifth Avenue.

Since then Chen has weathered more than half a century, experiencing the ups and downs of a volatile and profitable market, where sales records were made to be broken, and has witnessed the final years of a company whose own history is embedded in that of contemporary China.

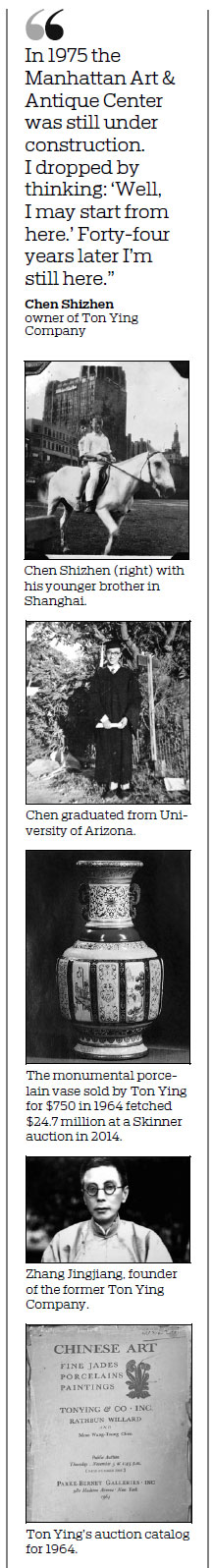

About 100 years ago the Ton Ying Company, one of the earliest concerns in New York to deal in Chinese antiques, was founded by Zhang Jingjiang, known as Chang Ching-chiang.

Chen was unable to see Zhang in person - the legendary man died in New York in 1950, more than a decade before Chen arrived there - but the latecomer has familiarized himself with the story of a man whose legacy he still palpably feels. "Zhang was born in 1877 in a business tycoon family in Zhejiang, southeastern China," says Chen, who has just received from a Chinese friend a biography of Zhang published in China in 2011.

"After having largely forsaken a political career due to illnesses that had crippled him and damaged his eyesight, he sought to become the 'third secretary' for the then Chinese minister to France Sun Baoqi.

"However, after arriving in Paris as part of Sun's delegation in December 1902, Zhang, led by his own business acumen, soon discovered a new calling. With financial backing from his father he set up a company with a gallery on Place de la Madeleine, importing Chinese tea, silk and art, before eventually branching out to London and New York."

That was just the beginning of a legend. On a steamship returning from China to Europe in 1906, Zhang had a chance encounter with Sun Yat-sen, founder of the Nationalist Party of China, who today is considered pivotal in overthrowing the rule of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) and thus ending the country's feudal history stretching over millennia.

Immediately enchanted, Zhang pledged support.

"The two established a code for Sun to use if he needed money: 'A' meant send 10,000 francs, 'B' meant send 20,000 francs and so forth," Chen says. "This was a pledge that Sun took only half seriously until 1907, when a cash-strapped Sun, with few donors to turn to for his revolutionary cause, sent a telegram to Zhang with the letter C. A few days later 30,000 francs appeared in Sun's bank account.

Drawing from the huge profit generated mainly by his sale of ancient Chinese artworks and antiques, Zhang was able to offer continued support to Sun. When Sun, afflicted by cancer, signed his will in Beijing in 1925, Zhang was at his deathbed.

By that time Zhang himself had become a key member of the Nationalist Party and was viewed as a mentor by Chiang Kai-shek, who later succeeded Sun as the party leader. However, Zhang fell out with his protege in the 1930s and left China in 1938, after the Japanese invasion. He eventually settled in New York, where he spent the last decade of his life and was buried at Ferncliff Cemetery in Westchester county, about 40 kilometers north of Manhattan.

Two years before Zhang left China, in 1936, Chen was born in Shanghai into a business family whose wealth, although utterly incomparable to that of Zhang's family, was already big enough to open the boy's eyes and mind to the outside world.

"My father was a dentist who made a fortune by manufacturing and selling a hugely popular toothpaste," says Chen, whose own life path somehow reflects the adventurous streak of his entrepreneur father.

In 1952 the teenager boarded a train for Hong Kong, a cultural melting pot known as the Pearl of the Orient. There he attended, among other schools, La Salle College and became a schoolmate for the late Bruce Lee, Kung-fu master and action movie star.

Chen stayed in Hong Kong for six years before leaving for the US.

"I had become interested in physics and thought the US a better place for academic pursuits. An elder sister of mine was already in Arizona, married to an American Indian soldier she previously met in Shanghai. So I went there."

Attending the University of Arizona, Chen studied plasma physics, before arriving in New York in 1963, doing research in the astronomy department of Columbia University.

"It was during this time that I worked part-time for Ton Ying," Chen says, citing the influence of his uncle, Liu Linsheng, who is married to a cousin of Chen's father. A writer-scholar, Liu was an art adviser for the Chinese Nationalist Government after World War II as the country tried to retrieve from Japan some of its most-treasured art works looted during the war.

"We had some star clients. Mr Rockefeller was one, who was not at all that picky when it came to choosing for a museum donation. Then there were Gloria Vanderbilt, the heiress and actress, and the actors Anthony Quinn and Richard Chamberlain."

There was also Benjamin Altman, the man who founded the namesake luxury department store, and Arthur M. Sackler, the psychiatrist and philanthropist whose collection of Chinese art works and antiques today fill, among others, the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the Met) in New York and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum of Art and Archaeology at Peking University in Beijing.

The recent media coverage of the opioid epidemic has embroiled and disgraced the Sackler family, whose members were behind the hugely effective marketing of OxyCotin, an opioid drug believed to have claimed hundreds of thousands of lives from overdose over the past 20 years.

"I myself had almost gone into marketing," says Chen who, after university, held three college teaching posts and worked for several companies. "That's when I got letters from father asking me to try to explore the US market for a brand of concentrated mouth wash and aftershave he had just launched."

The idea was dropped after Chen found out that clinical tests, thus a lot of money, were required for the products to be sold in the US. Today two sample bottles of half-evaporated yellow liquids lie in a corner of Chen's store, "a reminder of my past effort", as he puts it.

By that time Zhang had long since died. After the death of his successor and brother-in-law Yao Changfu (more famously known as C.F. Yao) in 1963, the company struggled. When Chen, bored with "having a boss in my life", decided to strike out on his own, it was more than a decade since Ton Ying had held its last auction at Parke-Bernet Galleries in New York, in 1964.

"In 1975 the Manhattan Art & Antique Center was still under construction. I dropped by thinking: 'Well, I may start from here.' Forty-four years later I'm still here," he says.

A longtime presence carries its own benefits. Ask to see Chinese antiques, and almost every shop owner within the building will direct you to Chen's treasure trove, which is impossible to miss.

Guarding the door is a blue and white porcelain vase almost two meters high decorated with writhing dragons. Behind the glass door a miscellany of things jostle for attention: a broadly smiling pottery boy, an intricately carved bamboo brush holder, a beautifully realized coral figurine mounted on a wooden stand, and shelf after shelf of jade and porcelain wares, followed by a retinue of snuff bottles. All swarm this 100 square meter space, which seems barely half its size because of how cramped it is. On the upper edge of the door hangs a plaque that reads: Ton Ying.

"Zhang's Ton Ying Company does not exist now, but I want to continue the memory, even in a small way," says Chen, who attributes a sizable part of all the antiques in his store now on East 55th Street to the old company. "They were passed to me through my uncle, who bought in a lot during the company's final years and who passed away in 1980 in San Francisco."

Over the years Chen has done his own fair share of research, carefully collecting every piece of information he could find on the old Ton Ying Company, an effort that has resulted in a thick portfolio of newspaper cuttings, printed archival materials and the company's auction catalogs, with the final prices next to each specific item. They are mostly two or three-digit numbers.

"In 1964 a one-room apartment near Columbia University cost me $50 a month," Chen says. "And a porcelain vase made by a master craftsman at the royal kiln of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province routinely fetched between $50 and $200. Today you cannot expect to save a few months' rent and buy something with a hundreds-of-thousands-dollar asking price at the auction."

In September 2014 a monumental imperial Qing Dynasty vase was sold at auction for $24.7 million at the Boston-based auction house Skinner, topping all sales of Qing Dynasty vases in the US to that point. The anonymous buyer was believed to be from the Chinese mainland.

"There were mainly three factors that contributed to the phenomenal sale," Chen says. "First is its size, measuring 34.5 inches (87.6 cm). Second is its overall decoration that employed a wide range of techniques, which in turn gives it the nickname Ci Mu Ping, or 'Mother of all ceramics'.

"Last but not least is that this vase is almost identical to one housed by Beijing's Palace Museum, and is one of only two of its kind."

In an interview with Antiques and the Arts Weekly, Judith Dowling, the Harvard-trained expert who presided over the record-breaking sale, said the vase "was last seen publicly in 1964 at Parke-Bernet Galleries in New York, where it was in a sale of Asian things belonging to Ton Ying & Company".

"They encountered me at preview and asked to photocopy that auction catalog of 1964, which includes a detailed description and a full-page black-and-white picture of the vase."

On the fringe of the yellow page, beside the description, a number had been written down: 750.

"That amount is a clear indicator that people understood its value even back then. But no one had quite anticipated the rise," Chen says.

"Since the mid-1990s the market for Chinese antiques has shifted gradually from the US and Europe to China, as the Chinese are rediscovering their own cultural heritage."

Competition increased, but the real threat, Chen says, comes from online auctions.

"This is something I cannot see myself going into," says this man who has never owned a mobile phone and sees no need to have one.

"Buying an antique is essentially a touch-feel business."

Life has not changed much for Chen over 40 years. Every day he gets on a bus in the late morning and heads for the store from his home near Columbia University, just steps away from where he lived when he first arrived in New York.

"The benefit of this is that I got to go to all the events held at the university. I've never been too far away from what I used to do. Antiques and astronomy - my life has been running on the dual tracks of the past and the future."

Since leaving Shanghai in the 1950s Chen has gone back twice, in 2005 and 2013. His mother died in 1974, followed by his father seven years later. In his will he left the family villa in Xiamen, Fujian province, the scenic island city in southern China, to Chen, whom he believed "tends to think more" than his other children.

"Our house in Shanghai had to go, due to the construction of an underground tram line," he says.

Chen, an opera aficionado, has regularly attended performances at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Between 1985 and 2002 he sampled a large part of the city's countless restaurants offering unique dining experiences.

"I always went with a food critic, either from the Daily News or The New York Times, who diligently wrote down my opinions," he says. "Some asked me: Why don't you write yourself? Inertia ... you know, I'm a physics student.

"No other city is more like Shanghai than New York," said Chen, who in the late 1940s and 50s tapped into the Chinese city's hedonistic tradition, following his father to its famed theater houses from time to time.

The passing of time has given him a slightly hunched back and huge eye bags, but tastes acquired early in life are unchanged.

In 1952, upon Chen's departure from Shanghai to Hong Kong, his father asked the young man to take with him one of the most valuable things in the family: an ink and color on paper by Zhang Daqian (Chang Dai-chien), widely regarded as one of the most accomplished Chinese artists of the 20th century.

That painting, featuring a classical beauty in flowing robes, is painted in Zhang's signature style heavily influenced by the cave paintings in the Dunhuang Grottoes in northwestern China.

"I took that painting for the artist to see during one of his visits to the US in the 1960s, and he offered to buy it back for $8,000 together with two of his more recent works," Chen says.

"I declined. It's still with me now."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

|

|

|

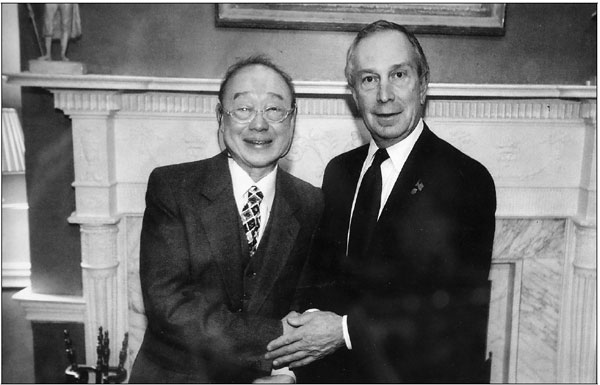

Chen Shizhen with Michael Bloomberg, the former mayor of New York City. Photos by Judy Zhu / China Daily |

(China Daily Global 05/25/2019 page16)