Where is Shangri-La?

The geographic and cultural locations in James Hilton's iconic novel may have remained a mystery for one simple reason

Shangri-La, something people know but can't define. Is it an earthly paradise? A hotel chain? A Chinese city or town? A Tibetan Utopia?

The word first appears in the 1933 novel Lost Horizon, written by English author James Hilton. It is described as some hidden valley with a lamasery overlooking it and a perfect snow-coned peak rising above, whose inhabitants have learned the secret of inner peace and extraordinary long life.

|

Nyorophu Island in Lugu Lake where Austrian American botanist Jospeh Rock used to stay on his way to Muli. Jack Yao / For China Daily |

|

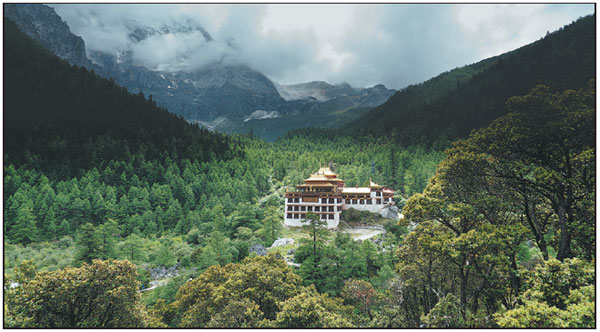

The Chonggu Monastery in Yading National Park in Daocheng county, Sichuan province. D J Clark / China Daily |

In the book, star English diplomat Hugh Conway and three others are kidnapped in a stolen airliner that takes them from Kabul to a crash landing in the Kunlun Mountains in Xinjiang of western China. Conway and his companions are rescued and taken to Shangri-La where each finds contentment though they are not free to leave.

Lost Horizon was a best-seller. It became the first book to be mass produced in paperback. The story was soon made into an Oscar winning Hollywood movie with Frank Capra directing and Hollywood's most bankable actor, Ronald Colman, in the lead role. People were convinced that James Hilton had based Shangri-La on a real place and expeditions (including one in 1938, sent by the Nazi regime in Germany) have gone to look for it.

If you ask Chinese people, "Where is Shangri-La?" they won't point to Xinjiang but more likely to northern Yunnan, 2,000 kilometers away and that's because of Joseph Rock, an Austrian-American botanist who explored the area in the 1920s and 1930s. From his base in Lijiang he ventured out on plant-hunting expeditions in Yunnan and Sichuan provinces, publishing the stories of his travels in National Geographic magazine. It is these articles that many now believe James Hilton may have borrowed from to describe Shangri-La.

The similarities between the geography of Rock's adventures and Hilton's story were first pointed out by Xuan Ke, a son of Rock's secretary, who organized the translation of Lost Horizon into Mandarin in the late 1970s.

"The place described in the book Lost Horizon has never been disclosed, but we knew it was Muli and the surrounding area," 91-year-old Xuan Ke said in between interruptions from his grandchildren. "Zhongdian, Adunzi and Muli are all within that area."

All three places are neighbors. Zhongdian used to be the name of a county in Yunnan province, Adunzi is now within today's Deqin county, also in Yunnan. But Muli county, though adjacent, belongs to Sichuan province.

Prior to writing his book, Hilton researched the Tibetan-inhabited region in the British Museum's library in London and a number of recent articles from Rock were there at the time. However when questioned in numerous radio and newspaper interviews he did after the book became a sensation, Hilton never mentions Rock, but rather claims his influence came from the writings of Abbe Huc, a French priest who traveled through the Tibetan region in 1844.

Huc's diaries explain some of the ideological themes in Lost Horizon as does the idea of the mythical kingdom of Shambhala which Hilton had also read about. Shambhala is said to be north of India and, like Shangri-La, was a repository for learning and culture when war raged in the world around. Both Abbe Huc's route and the supposed location of Shambhala support the Kunlun Mountains as the location for Hilton's novel, yet the geographical and cultural features described in the book seem to have been lifted from Rock's National Geographic articles.

Soon after the name Shangri-La entered into the Chinese imagina-tion, counties and cities in the area competed to acquire the name to encourage tourism, first the county of Zhongdian in Yunnan in 2001, which later grows into a city, then Riwa town in neighboring Daocheng county in Sichuan. But Rock did not write about Zhongdian until after Lost Horizon was published.

Although Xuan Ke was the first to see the similarities between Shangri-La and Rock's writings, it was an American mountaineer and lawyer, Ted Vaill, who narrowed down the location.

Vaill thoroughly researched the links between Rock's published articles between 1925 and 1931 and drew up a list of 22 points of similarity. He went on the first of two expeditions to Muli in 1999 and produced a film about his findings. For this, he interviewed Jane Wyatt, co-star of the 1937 movie who recounted that Hilton had told her that Rock's National Geographic articles had indeed influenced him. Unfortunately, when Wyatt told Vaill this, the tape recorder had already stopped rolling. After Wyatt's death, we only have Vaill's word of her statement.

Vaill followed the same route that Joseph Rock described in his 1931 article, climbing up to 4,800 meters and looping around the snow mountains of Xiannairi, Xianuoduoji and Yangmaiyong.

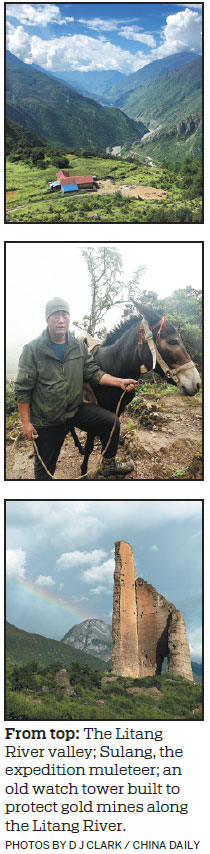

Memory of Rock lingers among local Chinese today. Sulang, a muleteer, knew of him through the stories of his grandfather, who was sent by the then lama king of Muli as a guard on Rock's 1929 expedition.

"He's the second one in," Sulang pointed out when shown a photograph of the explorer with his guides. "At that time, there were a lot of bandits in the mountains. He took his gun and knife, and wearing our traditional Tibetan clothes, accompanied Rock all the way."

Sulang said that the clothing worn in the film version of Lost Horizon was similar to what his grandfather wore. This was significant as, with Hilton advising in the movie's production, it appeared to be another link with him having used Rock's articles for reference.

Following the route of Rock and, much later, Vaill, it can be concluded that:

Muli and the upper Shou-Lu valley (as Rock called it, now the Shuiluo valley), like Shangri-La, are inaccessible in the snows.

There are gold deposits both in real Muli and in fictional Shangri-La.

When Conway escapes from Shangri-La, he arrives in Kangding, just north of Muli, and when he returns at the end of the book, he travels back through northern Thailand. Neither route would work for the Kunlun Mountains.

The villagers were not allowed to (or couldn't) leave their valley in either Shangri-La or the kingdom of Muli.

The clothing and local shrines in the movie are from Muli, not the Kunlun Mountains.

According to Vaill, the co-star of the movie Wyatt said that Hilton told her that he had read and been influenced by Rock's articles.

Above all (literally) there was the snow cone peak of Yangmaiyong, which Rock describes as a "peerless pyramid ... the finest mountain my eyes ever beheld". In his descriptions of it and in reality, it was hard to doubt that this was the inspiration for Karakal, the fictional mountain that hangs above the fabled valley of Shangri-La, described by Hilton as "the loveliest mountain on Earth, ... an almost perfect cone of snow, simple in outline as if a child had drawn it".

But there were also geographical inconsistencies. In the Lost Horizon, the plane crashes in the Kunlun range and this is where a friend of Conway goes searching for him at the end of the book.

So, was the paradise valley of Shangri-La based on Rock's accounts of Muli? To a large extent, yes. Even though the location of the air crash at the start is in the Kunlun Mountains, it is evident that many of the "on the ground" details come from Rock's exploration accounts, particularly his July 1931 National Geographic article, Konka Risumgongha, Holy Mountain of the Outlaws. Hilton had written his fiction in Woodford, England and never came to western China. But he did read extensively about it before he made his fiction up.

So why did Hilton not acknowledge his contemporary Rock when talking about the inspiration for his book but had no problem acknowledging Abbe Huc whose influence on Lost Horizon was far smaller?

In a 1936 article in the New York Sun, the journalist, Eileen Creelman, interviewed Hilton about a number of his books. She writes, "somehow the libel law crept into the conversation. Mr Hilton told how English authors had to be careful even about some of the places they described as someone had been successfully sued after he recognized the description of the cottage the plaintiff owned."

Did Hilton not acknowledge Rock for fear of legal action?

At the end of Lost Horizon, there is one telling paragraph where Hilton possibly hints toward the real influence for his novel. Conway's friend, Rutherford, who has been searching for him, meets a man who "had been traveling then for some American geological society". He says this explorer talked of meeting a Chinese man in the Kunlun Mountains who spoke excellent English and invited him to see his lamasery.

Was that explorer Rock? The answer is "probably yes".

(China Daily Global 05/22/2019 page16)