Gleaning the best of two worlds

Educators from the UK and China talk about the key learning points from their participation in a math teacher exchange program, Cao Chen reports in Shanghai.

Ian Pegrum's understanding of the role of Chinese pedagogy in mathematics used to be limited to what he had heard from others - that it was based on rote learning which offered little room for creativity.

But after undergoing a two-week China-UK math teacher program that was jointly launched by both countries in 2014, the 33-year-old Grade 2 teacher at the William Bellamy Primary School in Dagenham, Essex, has concluded that the Chinese pedagogy is nothing like what it is often described as.

In fact, he has even described it as being "a carefully-crafted learning journey".

"Children in Shanghai actually have plenty of opportunities to express their creativity through problem-solving activities," says Pegrum, who has been teaching for nine years.

"Contrary to perceptions that the Chinese style is very rigid, there is also much discussion in the classroom about the merits of different solutions to problems."

Pegrum was one of the UK teachers who got to observe math lessons at the Shanghai Huangpu District First Central Primary School and Pudong New Area New World Experimental Primary School for two weeks in 2018.

As of February 2019, about 700 teachers in primary and secondary schools from both countries have taken part in the program, according to its organizers in Shanghai. The exchange program also sees Shanghai math teachers visit British primary and secondary schools throughout the UK. All the Shanghai teachers involved in the program are highly experienced and are required to undergo a weeklong training session before they arrive in the UK.

Only those aged below 45 years old with at least three years of math teaching experience at primary or secondary schools in Shanghai are eligible, according to Huang Xingfeng, the program organizer in Shanghai. All these teachers also hold College English Test Band 6 certificates.

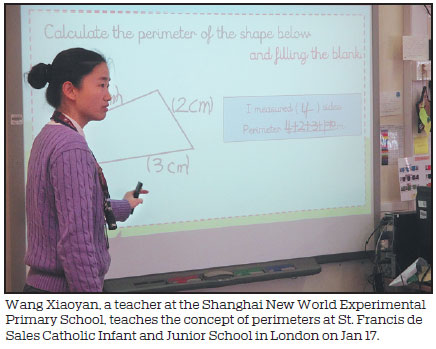

"During the training, teachers review Shanghai basic math teaching theories and approaches to better illustrate the Shanghai style, both theoretically and practically, to British teachers," says Huang, who is also an associate professor at the Research Institute for International and Comparative Education at Shanghai Normal University.

In addition, Chinese teachers with experience of UK schools inform teachers back in Shanghai about the school culture in the UK, education theories and principles, the types of teaching materials used, and the characteristics of British students.

The teaching content that Shanghai educators will use in British classrooms during the exchange is also adjusted to UK standards and culture.

For example, the units of currency in math questions are changed from the yuan, jiao and fen to the pound and penny. The multiplication tables that every Chinese pupil has to master are also translated into English. Even the cuisine that is found in Chinese math textbooks, such as Yangzhou fried rice and Shanghai steamed buns, is localized to include British foods like fish and chips, pies and tea.

Shanghai math pedagogy

The Shanghai math pedagogy has in the past decade gained recognition around the world for helping the city to become top for math in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development's program for international student assessment rankings for students aged 15 and 16 years old in 2009 and 2012. During this period, the UK government was also looking at different ways to improve math knowledge in the country, and it eventually decided to adopt some elements of Shanghai math instruction in the local curriculum.

Presently, about 5,000 of Britain's 16,000 primary schools have adopted the Shanghai math pedagogy. The UK government has also committed 41 million pounds ($54.5 million) to help at least 8,000 schools adopt this teaching method by 2020, according to earlier reports. Huang adds that Shanghai math textbooks for Grade 1 to 6 students have also been made available for use in UK classrooms since 2017.

"The exchange program does not mean to replicate each other's teaching approaches, but to learn from each other," says Zhang Minxuan, program leader and dean of the Research Institute for International and Comparative Education at Shanghai Normal University.

"Shanghai math practitioners can learn to further integrate cutting-edge technology into our basic mathematics education," adds Zhang as he points out that English math teachers often use computers to create mathematical models for homework.

Learning pace

Naturally, due to cultural differences, not all elements of the Shanghai method can be easily adopted into the UK system. The results of a study by Sheffield Hallam University which were released in January stated that while Key Stage 1 math pupils had benefitted from the Shanghai method, the same could not be said for Key Stage 2 children.

However, one aspect of the Shanghai method that has already been implemented in the UK curriculum is the pace of learning, says Pegrum, who is also a math mastery specialist with the National Centre for Excellence in the Teaching of Mathematics in the UK.

While the Shanghai method is centered on slower lessons that are focused on helping students achieve small, incremental steps in learning, British educators have been used to a faster pace.

"Keeping all the children together and having them do the same learning, ensuring the learning has small steps, providing children with a framework and vocabulary for their reasoning in the form of sentence stems, are some of Shanghai teaching aspects that are applicable in a UK classroom," he says.

Natalie Pullen, a British math teacher at the Northern Parade schools in Portsmouth, also lauded the Shanghai method, saying that Chinese teachers are trained to deliver a planned teaching sequence which involves clever practice that moves learning forward at a rapid pace.

"In contrast, in a typical English school, there might be a shorter teaching sequence followed by some independent practice, which feels less connected and interactive, even though this is not the case in all schools."

According to Martyn Kelly, deputy head teacher at the Front Street Primary School in Whickham, Gateshead, British teachers have historically been expected to accelerate children onto new content and keep challenging them through gaps in their learning. But this approach has changed since the exchange programs began.

"Teachers are now covering concepts with more depth and layers to learning. This is an approach that we are keen to follow and develop further at Front Street Primary," he says, before noting that a slower approach has already proved to be beneficial for slow learners.

"Children feel more confident when the lessons are slower. To create the most impact, we need a UK-specific approach that features a balance between the Shanghai style and our own methods of teaching."

Organizational differences

Another key difference between the UK and Shanghai pedagogies lies in the way that classrooms and teachers are managed.

For example, there is no streaming according to ability in Shanghai. Students, regardless of their mastery in the subject, undergo the same curriculum. In the UK, students who struggle are provided with greater support while those who excel are given one that will challenge them.

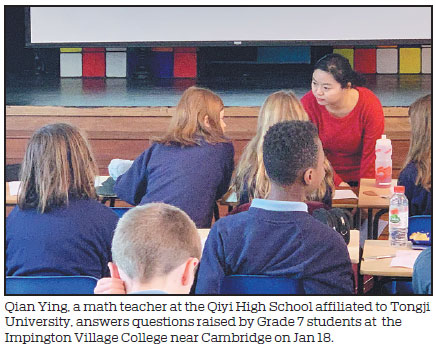

Qian Ying, a math teacher at the Qiyi High School affiliated to Tongji University who visited three high schools in the UK in 2015 and 2019, said that the British method is more gracious to students who struggle with the lessons.

"Students have to correctly solve a problem before getting to move on to a more difficult one. This approach is good for helping children who aren't as proficient in math to realize their potential and build confidence in the subject," she says.

Meanwhile, Livia Mitson from the Impington Village College near Cambridge, a combined junior and senior high school for students aged from 11 to 18, says that she also sees advantages in the Chinese approach of grouping students together regardless of their ability. Doing so, she explains, encourages students to help one another.

Another key organizational difference is related to the teachers.

"Each Shanghai teacher specializes in a specific subject, but most British teachers in primary and secondary schools teach many subjects. It is therefore harder to specialize and perfect our skills in math," says Pullen.

According to Mark Boylan, the head of the Sheffield Hallam team that evaluated the exchange program, Shanghai teachers receive some 500 hours of subject-specific training during the first five years of their career and are allowed more time to plan their lessons. In contrast, UK teachers receive just a third of that training.

Textbooks, Pullen adds, is another factor. While the use of textbooks in Shanghai is largely standardized, the same cannot be said for schools in the UK.

Making the process fun

One aspect of the UK approach that some Shanghai teachers have been intrigued by is the focus on incorporating fun into the learning process.

Liu Jiandong, a math teacher at the Shanghai Huangpu District First Central Primary School who has participated in three exchanges to the UK, says he is amazed at how British teachers often apply math to real life scenarios to make learning more relatable.

"An English math class usually lasts between 45 and 90 minutes, much longer than a standard 35-minute Chinese class. This allows teachers to place more emphasis on the fun of learning," says Liu.

He recalls that in one lesson on units of weight, a British teacher brought a suitcase to class and got the students to help the Shanghai teachers fill the bag up with food till it weighed 23 kilograms.

"This interesting and interactive approach helps children to feel how heavy a 23-kg baggage is. In Shanghai, the context of math questions for children is usually abstract and lacks a connection to the real world," he explains.

In some UK primary schools, students get to learn the principles of math through role-playing, such as shopping for goods or vendors selling their wares. According to Mitson, the role-playing area would change six times a year to allow students to take on different roles.

Liu also noticed that UK teachers often used a range of teaching tools, such as rectangular bars, colored paper and balls of different sizes, to make lessons more interesting. He says Shanghai teachers could adopt that.

Qian shares this sentiment. She points out that teachers in the UK often use an educational software called Formulator Tarsia to create activities in the form of jigsaws or dominos that help to engage the kids further.

"Children learn math through playing games on the software. It is a fun way to develop kids' intelligence and interest. I am also a fan of the software now," says Qian.

Contact the writer at caochen@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Liu Jiandong (center), a math teacher at the Shanghai Huangpu District First Central Primary School, helps students to understand the concept of fractions at the Nightingale Primary School in London on Nov 8, 2017. Photos provided to China Daily |

|

Natalie Pullen (second from left), a British math teacher at the Northern Parade schools in Portsmouth, poses with Shanghai and British math teachers at the school in January. |

(China Daily 03/01/2019 page15)