Forged unity now breaks apart

Gallup's 15-year-old poll of US' national pride has hit its lowest point this year

For a time, it felt like the attack that shattered the United States had also brought it together.

After the attacks on Sept 11, 2001, signs of newfound unity seemed to well up everywhere, from the homes where US flags appeared virtually overnight to the Capitol steps where lawmakers pushed aside party lines to sing "God Bless America" together.

That cohesion feels vanishingly distant as the 15th anniversary of the attacks arrives on Sunday. Gallup's 15-year-old poll of US' national pride hit its lowest-ever point this year. In a country that now seems carved up by door-slamming disputes over race, immigration, national security, policing and politics, people impelled by the spirit of common purpose after Sept 11 rue how much it has slipped away.

Jon Hile figured he could help the ground zero cleanup because he worked in industrial air pollution control. So he traveled from Louisville, Kentucky, to volunteer, and it is not exaggerating to say the experience changed his life. He came home and became a firefighter.

Hile, who now runs a risk management firm, remembers it as a time of communal kindness, when "everybody understood how quickly things could change ... and how quickly you could feel vulnerable".

A decade and a half later, he sees a nation where economic stress has pushed many people to look out for themselves. Where people stick to their comfort zones.

"I wish that we truly remembered," he said, "like we said we'd never forget."

Terrorism barely registered among US citizens' top worries in early September 2001, but amid economic concerns, a Gallup poll around then found only 43 percent of US people were satisfied with the way things were going.

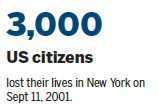

Then, in under two hours on Sept 11, the nation lost nearly 3,000 people, two of its tallest buildings and its sense of impregnability. But out of the shock, fear and sorrow rose a feeling of regaining some things, too - a shared identity, a heartfelt commitment to the nation indivisible.

Stores ran out of flags. US citizens from coast to coast cupped candle flames and prayed at vigils, gave blood and billions of dollars, cheered firefighters and police. Military recruits cited the attacks as they signed up.

Congress scrubbed partisanship to pass a $40 billion anti-terrorism and victim aid measure three days after the attacks, and approval ratings for lawmakers and the president sped to historic highs.

"I really saw people stand up for America. ... And I was very proud of that," said Maria Medrano-Nehls, a retired state library agency worker in Nebraska. Her foster daughter and niece, Army National Guard Master Sergeant Linda Tarango-Griess, was killed by a roadside bomb in Iraq in 2004.

Now, Medrano-Nehls thinks weariness from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and combative politics have pried US citizens apart, and it pains her to think of the military serving a country so torn.

Larry Brook can still picture the crowd at a post-9/11 interfaith vigil at an amphitheater in Pelham, Alabama. The numbers seemed a tangible measure of an urge to come together.

"Now? I don't think we're anywhere close," Brook said.

Three days after Sept 11, Joseph Esposito was at smoldering ground zero as Republican then-president George W. Bush grabbed a bullhorn and vowed the attackers "will hear all of us soon". The moment became an emblem of US strength and resolve, and Esposito, then the New York Police Department's top uniformed officer, was struck by "the camaraderie, the unity" of those days.

He remembers the support police enjoyed then, and how much the tone had changed by the time of the Occupy Wall Street protests in 2011, when police arrested hundreds of demonstrators, many of whom said police unjustly rounded and roughed them up.

Now the city's emergency management commissioner, Esposito has watched from the sidelines as a national protest movement has erupted in recent years from police killings of unarmed black men, and as police themselves have been killed by gunmen claiming vengeance.

These days, Esposito hopes his job can be unifying. He wants people to feel that the city helps neighborhoods equally to handle disaster. "The 1 percenters should not be better prepared than the 99 percent," he said.

|

Children peer into the south reflecting pool at the National September 11 Memorial and Museum in New York, on Sept 1.Andrew Kelly / Reuters |

|

3 World Trade Center (center), under construction in New York on June 22.Mark Lennihan / Associa Ted Press |

(China Daily 09/10/2016 page10)