Overworked officers quitting profession

Country needs another 6,000 qualified crime scene investigators to fill vacant positions. Cao Yin reports.

After 14 years as a forensics officer, Ji Chunwei reluctantly resigned his post as a crime scene investigator. He blamed the heavy workload for forcing him out of a job he regarded as important and worthwhile.

"I loved the job, but as the only crime scene investigator at a public security department in Zhongshan, Guangdong province, I had to deal with more than 200 cases every year, which meant I rarely stopped at weekends, let alone took a vacation," said the 39-year-old, who became a criminal lawyer in May 2014.

Luo Yaping, a professor at the People's Public Security University of China who specializes in the study of investigative skills, said investigators are under great pressure. "There are so few forensics officers that they are being swamped by the rapid rise in the number of cases handled by the grassroots public security authorities," she said, adding that the shortage of professional talent has never been so pronounced.

"A forensics officer has to conduct at least 100autopsies a year, in addition to working on at least 200 injury cases over the same time frame. The pressure imposed by the heavy workload is immense," she said.

In 2014, Yangcheng Evening News reported that China's public security bureaus, prosecuting authorities and courts needed another 6,000 investigators to fill vacant positions.

|

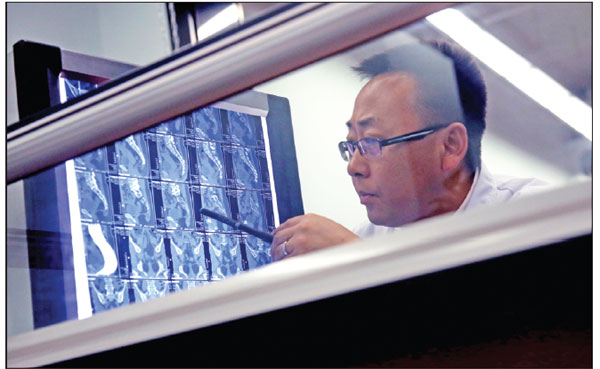

Wang Peng, a forensics officer and deputy director of the Beijing Tianmu Judicial Expertise Institute, identifying injuries via xrays at his office in Beijing. Jiang Dong / China Daily |

"Not many high school students register for the forensics major because the study process is so difficult. That means few people are engaged in the work after graduation," Luo said.

Forensics majors train at medical schools, and graduates who choose to work in the profession have two options. They can take the national civil servants' exam and work as an investigator at a public security bureau, earning about 5,000 yuan ($750) a month. Alternatively, they can study for the national forensics qualification and work for an independent judicial institute registered with the Ministry of Justice.

"It's not easy to gain entry to medical school, and the civil servants' exam is even more difficult," Luo said. "So you can imagine how few students end up as forensics officers."

There are no official statistics to indicate how many crime scene investigators work for China's public security authorities, but the ministry confirmed that in November the number working at registered judicial institutes was 4,924, including 2,523 who specialized in forensic identification, a rise of 50 from 2014.

The number is far from enough, according to Luo. "Some of the smaller independent institutes have just one or two officers qualified to assess and identify injuries," she said.

"Forensics officers in areas where transportation is underdeveloped, such as Qinghai and Sichuan provinces, often take several days to arrive at crime scenes because there is no one else to do their work. That influences the quality of identification to some extent."

Ji knows all about the pressures. "I was required to appear at crime scenes almost immediately after a report was filed, but as the only professional with the district's public security body, it was really difficult to do that," he said.

Generally, crime scene investigators must be engaged from start to finish in cases where crime is suspected, especially those involving alleged homicide or intentional injury, he added.

"But in cases where death or injury is deemed to be accidental, such as traffic accidents and work-related injuries, the burden is often shared by forensics officers from independent institutes," he said.