The perfect partner is just an ocean away

Chinese businesses have joined the international match-making stakes and are still a little starry eyed

The business of buying or merging with overseas companies is not unlike looking for the perfect marriage partner: At times it may be OK to let your heart rule your head, but ultimately the decisions to be taken need strong doses of sober reflection.

Looked at this way you could say that over the past 15 years China's enterprises have fallen head over heels with mergers and acquisitions, have taken the plunge and are now enjoying the honeymoon.

The clearest evidence of the gusto with which the country has taken to this new way of life is the fact that in the first quarter of this year it was the world's largest acquirer in terms of the value of mergers and acquisitions, based on figures provided by Dealogic, a global financial data provider.

China announced a record $92 billion of overseas mergers and acquisitions deals from January to March this year, accounting for 30 percent of the world's total, Dealogic says.

In February the State-owned conglomerate China National Chemical Corp agreed to buy the Swiss agricultural group Syngenta for $43 billion, making it the largest foreign takeover by a Chinese company.

"Chinese companies are becoming big buyers globally," says Wang Yunfan, chief executive officer of Morning Whistle Group in Shanghai, a one-stop service provider in overseas mergers and acquisitions of Chinese capital.

The value of such activities has grown six years in a row, the total last year being $107 billion, Dealogic says.

"That number would have been unimaginable a decade ago," says Zhang Xiaoping, a business consultant and a keen observer of mergers and acquisitions.

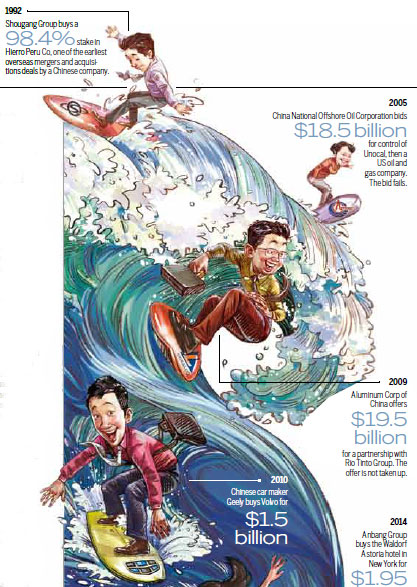

In 1992 Shougang Group bought a 98.4 percent stake in Hierro Peru Co in one of the earliest overseas mergers and acquisition deals by a Chinese company, he says.

However, it was not until 12 years later, after the National Development and Reform Commission streamlined rules on the management of overseas investment projects, that interest by Chinese concerns in overseas mergers and acquisitions really began to take off. That year the deals were worth $7 billion.

As with any quest for a good suitor, Chinese enterprises have had the odd rebuff or two on the mergers and acquisitions path over the past decade or so. In 2005, a bid of $18.5 billion by China National Offshore Oil Corporation for control of Unocal, then a US oil and gas company, fell flat. That too was the fate that Aluminum Corp of China had to accept after it offered $19.5 billion for a partnership with Anglo-Australian company Rio Tinto Group, one of the two largest suppliers of iron ore in the world, in 2009.

"One of the lessons of Aluminum Corp of China's failure to take over Rio Tinto Group is that you need to increase the opportunity cost of the deal," says David Xu, partner-in-charge of the advisory KPMG Northern China, who joined KPMG in 1997 and has been a specialist consultant in overseas mergers and acquisitions since 2005.

The failure of the Rio Tinto deal was the result of bulk commodities prices rising sharply, more than making up for a cancellation fee the company would have to pay, Xu says.

Henry Cai, chairman of the Asian-Europe growth capital investor AGIC Capital, says: "There has been a huge amount of overseas investment by Chinese companies over the past 15 years, but in half the cases the result has been failure. One of the main reasons is that Chinese companies have had little knowledge of industrial systems in other markets. There's a wave of overseas investment going on right now, but a company should only act when it really is ready; there is no need to rush."

The best prospects lie in "intellectualized and automatic sectors", Cai says.

Over the past three years private companies have emerged as one of the major players in overseas mergers and acquisitions, Xu says.

"Before 2013 few private companies came to us for advice on overseas mergers and acquisitions, but now such business almost equals that of State-owned enterprises."

Private companies are more nimble in their decision making, and they will continue to be an increasingly important force in overseas mergers and acquisitions, Xu says, citing the insurance company Anbang, the investment group Fosun and the conglomerate Dalian Wanda as examples. All three have been highly active acquirers internationally.

"You really need three to five years to gauge whether one of these overseas deals is successful because integrating two corporate entities can be a fraught task."

Of all the overseas deals Xu has studied, those of the automotive components maker Wanxiang Group in the United States have been among the most impressive, he says.

"The size of Wanxiang's M&A deals has not been that big, and the price has been relatively reasonable."

Since its first acquisition of a solar energy plant in the US in 1996, Wanxiang has bought 28 plants in the US, producing auto spare parts for GM, Ford and Daimler Chrysler.

Ni Ping, president of Wanxiang Group's US company, says the way existing staff and those of a newly acquired company are integrated can determine whether the acquisition succeeds or not. Having local staff is particularly important for Chinese companies, he says. Wanxiang employs more than 6,500 people in the US.

Despite the impressive growth of Chinese enterprises' overseas mergers and acquisitions, the proportion of Chinese assets overseas remains minuscule compared with those of developed markets. Europe, the United States and Japan each have about 40 percent of their business assets overseas, and the figure for China is just 8 percent, Morning Whistle says.

"A lack of skilled people is one of the biggest problems," Xu says. "In recent years Chinese companies have taken on more international M&A talent to manage mergers and acquisitions process, but it will take a bit longer to get other professionals like engineers good at communicating with their counterparts in the acquired foreign company to get up to speed."

According to a survey by the University of International Business and Economics in Beijing, Chinese companies lack translation and other language skills needed to expand overseas.

These can still be counted as the early days of Chinese companies making transnational acquisitions, says Shen Danyang, a spokesman for the Ministry of Commerce.

Chinese overseas investment accounts for just 3.4 percent of the world's total, he says, the figure for the US being 24.4 percent. Britain, France, Germany and Japan are also ahead of China on this count, he says.

Shi Jing contributed to this story.

(China Daily 05/30/2016 page14)