Iron arteries pump new life

The social changes that high-speed trains have wrought add up to far more than the hours and minutes saved

When Zhou Fengying took the 320-kilometer train ride from Wuhan to Yichang about 35 years ago, her employer gave her a day off - to sleep off the rigors of what seemed like an impossibly long journey.

Zhou was an employee of the urban construction administration of Yichang at the time and she frequently made such trips to the provincial capital of Hubei on local government business.

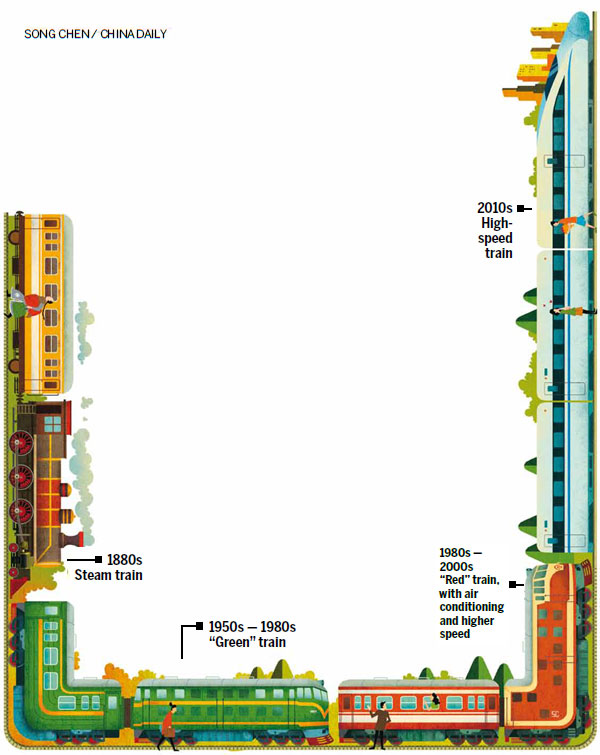

The trip lasted between 11 and 12 hours, partly because there was no direct rail link between the two cities, and the trains had to use a track on which their speed was restricted to less than 40 km/h, says Zhou, now 60. In addition, those crammed into the trains had to survive the journey in dowdy green carriages that were grubby and had no air conditioning.

"The trains were absolutely packed. People occupied any space they could find. I used to have people lying under my seat and others beside my feet."

So in the 1990s when long-haul bus services began running, they were like a breath of fresh air, and Zhou seized the opportunity to use them. These buses were more frequent than the trains, they were air-conditioned and suddenly travel time was halved, to less than six hours.

Another couple of decades on, those buses, which had seemed so advanced, themselves took a back seat when Zhou decided to travel to Wuhan to see her son. That day in 2012 she took one of the sparkling new high-speed trains that had been put on that year linking the two cities. The stifling, rackety trip that had once taken as much as 12 hours had now been transformed into a leisurely, smooth jaunt lasting just two hours.

"The train was so clean and quiet," Zhou says. "You could do a lot of different things on the trip, like writing and reading. I guess one reason the train was so clean was that it looked so good that anyone inclined to litter felt too embarrassed to do so."

In this 21st-century travel, too, noisy arguments over seats had given way to peace and civility, Zhou says.

"I guess one reason for that is that since it's just two hours to Wuhan, people were not as hot-headed as they used to be if they had to stand."

As the arteries of China's high-speed railway network have continued to grow over the past eight years, they have also delivered efficient and punctual service at highly affordable prices, and have greatly changed the way Chinese regard getting about the country.

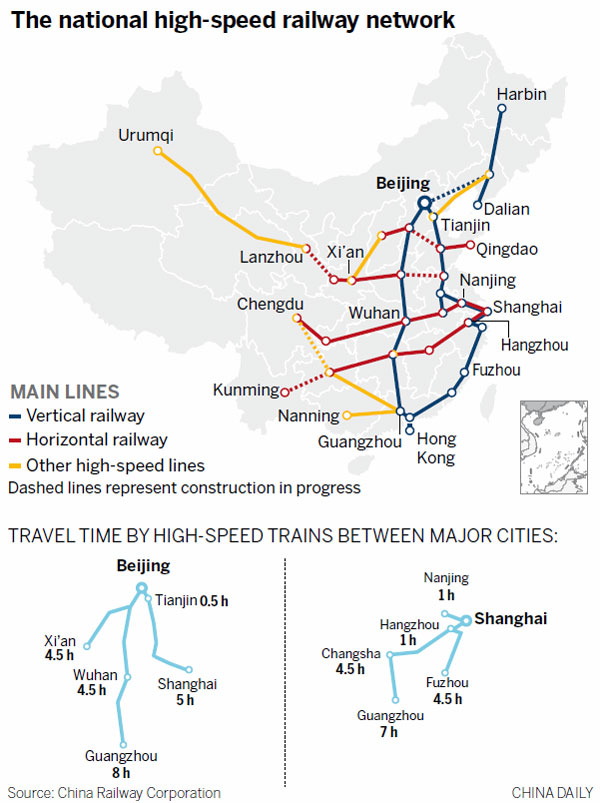

The first high-speed railway line, 120 km long, between Beijing and Tianjin, opened in 2008, and by the end of last year another 19,000 km of high-speed rail lines had been laid and put into service. That equates to an average of 2,700 km of new lines each year - about the total length of the high-speed rail lines in Japan.

Indeed, China now has the world's longest high-speed rail network, and it accounts for 60 percent of the world's total, Sheng Guangzu, general manager of China Railway Corp, said in January.

One change this sprawling network has wrought is people going on sightseeing trips far away from home over three-day holidays, or attending weddings far away over the weekend, which in the past would have been regarded as impractical.

Zhou's son, her only child, moved to Wuhan several years ago, and she says she had thought it would be difficult for her to see the family that often or for her to take care of her grandson. She also had her own parents to look after in Yichang.

"If I helped them with the baby in Wuhan, I could not take care of my parents in Yichang. If I brought the baby back to Yichang he would need to go to Wuhan for vaccine shots from time to time, and that was impossible without good transport."

But that has now changed, she says. Her second grandchild, born last year, now lives with her in Yichang. "When the baby needs vaccine shots and when her parents miss her I hop on the train and head to Wuhan."

The fast rail transport network is also having a significant impact on the way the country does business. Inland cities that had little appeal to investors because of a paucity of good transport links have now become attractive. Particularly since the central government has called for economic restructuring and industrial upgrading, inland cities linked to the national high-speed rail network have become preferred destinations for traditional industries moving their operations from coastal areas.

One example is Chenzhou in Hunan province, a city that used to rely heavily on mining. The city is on the border of Hunan and Guangdong provinces, but is closer to Guangzhou, the latter's capital and the country's economic engine, than to other cities in Hunan. However, until 2009 the fastest train from Chenzhou to Guangzhou took six hours. This acted as a deadweight on Chenzhou whenever it sought investment, and local officials in charge of attracting investment were often thwarted as they competed with cities with airports or with highway access.

That all changed in 2009 when the Wuhan-Guangzhou high-speed railway opened, and suddenly Chenzhou found itself just 90 minutes away. That reduction in travel time and costs has prompted a number of companies to set up production centers in Chenzhou, including Royal Philips NV and Delta Group. In 2014 the city shot up in provincial rankings to be behind only the capital, Changsha, in its use of foreign capital, media reported.

Experts say there are many other small cities in China's western and central provinces and regions that can benefit from the sprawling high-speed railway network as Chenzhou has.

Liu Bin, a researcher at the comprehensive transport institute at the National Development and Research Commission, says the high-speed railways can help make inland areas more competitive in raw materials and manufacturing.

The Government Work Report that Premier Li Keqiang delivered in March said the high-speed railway network will be 30,000 km long by the end of 2020, linking 80 percent of major cities nationwide. It means 11,000 km of high-speed railways will have been laid out in five years, or 2,200 km a year on average.

Wang Yanfei contributed to this story.

2004

The national mid- and long-term railway plan is drafted, with a goal of building a 12,000-km railway network with an operating speed above 200 km/h by 2020.

2008

The Ministry of Railways and the Ministry of Science and Technology sign a deal in February on jointly developing a high-speed train operating at 380 km/h.

The country's first high-speed railway, between Beijing and Tianjin, starts operation on Aug 1.

Mid- and long-term railway planning is revised, changing the goal to building at least 16,000 km of high-speed railways by 2020.

2010

The Chinese designed and manufactured bullet train CRH380 sets a record of 486.1 km/h in a trial run.

2011

The Beijing-Shanghai High-speed Railway - China's longest high-speed rail line stretching 1,318 km - opens to traffic on June 30.

2012

The Harbin-Dalian High-speed Railway - the world's first high-speed railway in a frigid zone - starts operating on Dec 1.

(China Daily 05/30/2016 page7)