The ups and downs of Latin adventure

|

A trade booth representing Brazilian businesses at the 110th Canton Fair in October. In 2010, $17 billion in Chinese investment flowed into Brazil, making China the country's largest foreign investor. Nelson Ching / Bloomberg |

It wasn't supposed to be like this.

Lin Peifeng, a Chinese engineer, points at a blueprint that shows a giant fertilizer chemical plant, along with two electric power plants, several warehouses and workers' dormitory buildings.

But outside the window of his container-turned temporary office, battered by the howling winter wind, stretches a tract of land thickly covered with withered yellow grass, dotted with occasional piles of coal in the distance.

In reality, there is only wilderness.

This construction site in Rio Grande - a northern city in South Argentina's Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego - is no ordinary one.

It dates back to early 2010, when, in a bid to meet the South American country's growing demand for fertilizers, three Chinese companies from the country's energy and coal chemical sector - Shaanxi Coal & Chemical Industry Group Co Ltd, Shaanxi Xinyida Investment Ltd and Jinduicheng Molybdenum Group Co Ltd - made a joint investment worth $1 billion, to deliver a plant that could produce 450,000 metric tons of ammonia and 800,000 tons of urea per year.

It is so far the largest Chinese investment in the whole Latin American region.

With the promise of fantastic prospects and support from both governments, agreements for the investment were signed to huge media fanfare on both sides of the world.

But the initial enthusiasm soon cooled and strains began to show.

Tension came to a head in April when a shipment of vital construction equipment and machinery was barred from entering a port in Argentina, due to the country's import restrictions.

Lin works for Tierra Del Fuego Power & Chemical Co Ltd, known as TEQSA in Spanish, a company set up by the three Chinese companies to take charge of the project.

The Argentine government has declined China Daily's repeated requests for comments on the issue, but lacking the necessary machinery, the construction work, supposed to have been finished by April, was also halted.

"There's not much to do here," added a Chinese construction worker at the site.

"I have put on 10 kilograms in weight."

Two years after the agreement was signed, the project is still no further than at the preliminary stage.

"There are troubles, troubles everyday," said Li Dacan, TEQSA's general manager, as he describes his work over the past three years.

TEQSA is only one of a wave of Chinese investments that has flowed to Latin American countries in recent years.

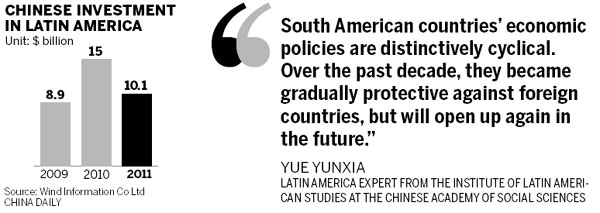

In 2011, the outflow of Chinese investments in the region stood at $10.1 billion, accounting for 16.8 percent of the country's total overseas investment volume, according to official data.

The Latin American region has now emerged as China's second-largest overseas investment destination, second only to Europe.

The headline figures might look like a massive success story on paper, but for many companies the reality is very different.

China is currently the region's third-largest trading partner - but there has been growing criticism in recent years of what is now a growing imbalance in trade between the two parties.

In 2011, total trade volume between China and Latin America jumped 31.5 percent from the previous year to $242 billion, according to official Chinese data.

Some 60 percent of China's imports from Latin American countries are made up of natural resources, while its exports to the region are dominated by processed or manufactured products.

Latin American producers have reacted badly to the influx of cheaper Chinese goods.

The Brazilian National Confederation of Industry, an industrial lobby, for instance, announced in January the establishment of a bilateral body with its counterparts in Argentina, as a way to combat import competition.

Several big names in Brazilian business have taken an active part, including Mafrig, the third-biggest Brazilian food processing company.

According to information from the Economist Intelligence Unit, participants in the body have prioritized the need to urgently tackle growing imports from China.

But growing investments being made in South America might be the key to helping ease the situation, and the imbalance, suggested economists and trade experts.

"One of the main reasons for the trade imbalance is that the manufacturing sector in Latin America is not very competitive," said Yue Yunxia, a Latin America specialist from the Institute of Latin American Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Investments, especially to help improve the industrial infrastructure in certain sectors and upgrade the quality of products and their manufacturing efficiency, are seen as especially favorable, Yue said.

Yet, there remains a strong reluctance toward foreign investments in many Latin American countries, said analysts and experts.

And even those who do manage to get a foothold, including an increasing number of Chinese companies, complained of various issues affecting success, such as political instability, government inefficiency, complicated legal and tax structures, and even problems with visa applications.

Local governments' attitudes toward foreign investment can also be ambiguous.

Brazil has seen a sharp increase in Chinese investment in recent years. By the end of 2009, the total volume of Chinese investment stood at $200 million.

In 2010 alone, $17 billion in Chinese investment flowed into Brazil, making China the country's largest foreign investor.

But despite China's enthusiasm to invest, the Brazilian government has seemed reluctant to facilitate the investments.

A well-known joke is that several bilateral business bodies - all claiming to be official China-Brazil chambers of commerce - compete for connections and business.

Another issue is that some Chinese companies have found their investments - and themselves - being used a pawn to gain power and popularity by competing political parties.

"They (the governments and political parties in Latin American countries) treat foreign investments in quite a different way from China," said TEQSA General Manager Li Dacan.

Success under strain

There are, of course, success stories, but even successes come with a degree of strain.

Shanghai-listed construction machinery giant Sany Heavy Industry Co Ltd, for instance, was one of the first Chinese investors in Brazil in the sector.

The company announced in March 2010 its first Latin American investment of $200 million in a production base in Sao Jose, two-hours' drive from the country's largest city, Sao Paulo.

The investment was Sany's largest in the Latin America region.

Over the past two years, it has seen explosive increases in its sales to local markets as a result.

In 2011, its sales reached $108 million compared with $30 million in the previous year. Competing with international players such as Caterpillar Inc, the world's biggest heavy machinery maker, some of Sany's products have become market leaders in Brazil.

But despite the growing sales, the company has admitted to difficulty in making profits.

"Labor costs are too high," said Xu Ming, assistant to the president of Sany.

He said the monthly salary for a middle-level manager in Brazil could stand at $7,000 on average, way above their Chinese counterparts and "almost the same as levels in the United States".

The Brazilian government also has localization regulations in force that mean if a foreign company wants to hire one Chinese worker, it must hire two local workers as a trade-off.

Sany currently has 345 employees in Brazil, 280 of which are local people, far above the stipulated localization ratio.

But having met the localization requirements, working visas are also still hard to apply. Even in cases of Chinese people hired in Brazil, all the necessary materials must be sent to the embassy back in China.

The application procedure can take months, and that's provided everything goes smoothly.

For a machinery manufacturer such as Sany, it is vital to have a skilled workforce, and their Brazilian employees at the production lines are in need of training by their Chinese counterparts.

"We cannot have the skilled Chinese workers we need in the workshop without working visas. But the application procedure consumes too much time, and often disrupts our schedules," Xu said.

Even top-level management can face the same dilemma.

Xu himself is waiting for his working visa to go to Brazil. A business visa grants people entry to the country, but they are still not allowed to work there.

The lack of management experience in Latin America poses another potential snag for Chinese companies.

Language and culture are a problem to begin with, and students in China studying Portuguese and Spanish remain a minority compared with the widely taught English.

In many Chinese companies, simple unfamiliarity with Latin culture can lead to avoidable disputes between local and Chinese employees.

In some extreme cases, the cultural barrier has affected business efficiency.

Most Chinese companies that achieved success in overseas markets mainly rely on their ability to respond fast to the local market's demands and provide products with decent quality and a reasonable price.

But compared with their rivals from Europe and the United States, Chinese companies need to improve their internal communications.

Adenilson Carvalho, head of human resources at Sany in Brazil, pointed out that some US companies are able to easily put employees of different nationalities into departments of different functions.

"But Chinese companies need to cross a wider cultural gap than US companies," he said.

Huge market potential and strong economic growth, especially at a time when the advanced economies such as the European Union and US are struggling with a sluggish economic recovery, make Latin American markets enormously attractive.

And so, despite the challenges posed by the investment environment and cultural barriers, Chinese companies still appear determined to stay and succeed in Latin America.

Bright prospects

"There is no doubt that Brazil will be a star country in the next decade," said Xu from Sany.

For his company, its Brazilian production base is being seen as a perfect springboard for products to be sold into other Latin American countries.

"Colombia, Peru and Ecuador, all these countries boast enormous market potential," he added.

Improved stability expected in the region in the long term also provides Chinese companies with a further reason to be optimistic, not least because of the strengthening ties in recent years between China and Mercosur - South America's leading trading bloc, known as the Common Market of the South, which aims to bring about the free movement of goods, capital, services and people among its member states.

"South American countries' economic policies are distinctively cyclical," added Yue from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

"Over the past decade they became gradually protective against foreign countries, but will open up again in the future."

During his recent four-nation visit to South America in June, Premier Wen Jiabao signed several trade and cooperation agreements with the countries he visited.

In Brazil, the two countries signed an accord to swap $30 billion worth of their currencies. Brazil and China also announced plans to share more financial information and enhance cooperation and investment in aerospace.

In Argentina, Wen and Argentina's President Cristina Fernandez signed accords on nuclear energy and for Chinese imports of Argentine horses and livestock, and some farm products. The two countries also inked a deal of a $2 billion loan to finance the upgrading of Argentina's Belgrano Cargas railway.

China currently has free trade agreements with Latin American countries, including Chile, Peru and Costa Rica.

And during a discussion between the two leaders, Wen and Fernandez talked about a free trade agreement between China and the Mercosur bloc.

Wen said he expected bilateral trade between China and Mercosur to reach $200 billion by 2016, up from $99 billion in 2011, Argentine official data showed.

For TEQSA, Wen's visit to Argentina marked a great opportunity to push for progress.

After rounds of stalled negotiations, a conclusion was finally reached that will see TEQSA selling a portion of its stock to an Argentine state-owned company and a private Argentine company, forming a new joint venture, the company said.

There are conditions attached: any equipment and machinery needed in the project, unless Argentine manufacturers cannot produce them, must be purchased in the local market, and the company should also employ as many local people as possible.

As a result, "the costs will be much higher than before and the company structure, which is already very intricate with people from three Chinese companies, will be further complicated", said Li Dacan, its general manager.

But Li said he is optimistic about the future prospects it presents.

Argentina currently consumes about 10 percent of the world's fertilizer but can produce only 4 percent.

"Everything will be fine if the plant starts production," he said.

Li also plans to put his years of experience in dealing with the Argentine government and local market to good use.

His next plan is to build an industrial park in Rio Grande, a tariff-free zone designated by the Argentine government, and invite more Chinese companies to invest.

"We have paid our dues. All these things can never be learned if we had stayed in China. And now we will make use of the experience to build a platform for other Chinese companies," Li said.

'End of the world'

For Lin Peifeng at TEQSA, the project has become part of his life.

"After a 30-hour flight, this is like the end of the world," Lin said.

Located near the southern tip of South America, Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, which means "Great Island of the Land of Fire", has extreme weather conditions as its name suggests.

In winter, there are only a few hours of sunlight and the strong, cutting wind howls all day outside his window.

"I couldn't sleep for the first couple of months," Lin said, and there were other things that needed getting used to, such as unreliable Internet connection, weak mobile phone signal, and the inconvenience of strikes from time to time.

In June, a large-scale strike by fuel truck drivers erupted in Argentina and stations in the city ran out of gasoline.

During those days, all the people in the office had to share one of the four cars the company has.

This is the first time Lin has been outside China, so the weekly get-together over a Chinese hot pot for all Chinese employees is a treat for those not yet used to the local food.

"We cannot find tofu here, so whenever there's someone coming from Buenos Aires, we ask them to bring some dried tofu, which is easy to carry," Lin said.

Buenos Aires is a four-hour flight from Rio Grande.

As winter approaches, it became too cold to do whatever remained possible to do on the construction site, so the company sent the last handful of Chinese construction workers back home.

Lin will soon join them.

When the snow thaws, maybe things will be better and easier, and he will return to Argentina.

But for the moment, he just waits for his flight ticket, to take him back to the warmth of home.

zhousiyu@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 07/24/2012 page13)