The answer is blowing in the wind

|

Workers deploying wind turbines at a wind farm in Jiujiang, Jiangxi province. China's installed wind-power capacity has doubled every year since 2005. Fu Jianbin / for China Daily |

Lagging grid development may hamper burgeoning industry

HOHHOT - It only takes 60 minutes to fly from Beijing to Hohhot, the capital of the Inner Mongolia autonomous region in North China. However, Hohhot still enjoys an unlimited supply of electricity, while many places in China are facing their most severe power shortages for years.

The resource-rich region of Inner Mongolia is China's powerhouse and produces more electricity than it can consume. This vast region is famous for its abundant resources: It is the country's largest producer of coal and is home to the world's largest rare-earth mine.

Now, it is rapidly becoming known as the wind-power center of China.

Vowing to become the country's upland Three Gorges - the site of a massive hydroelectric dam - the province has set a target of installing 33 gigawatts (gW) of wind capacity by 2015, equal to 20 percent of the region's total power generation.

By the end of June 2011, Inner Mongolia's grid-connected wind capacity had reached 12 gW, or 10 percent of the region's power generation, while the national average in China is 0.7 percent, according to the National Energy Administration (NEA).

This has put the province on a par with the world's leading wind-power countries such as Denmark and Spain.

Chifeng city, 600 kilometers (km) from Hohhot, is an ancient settlement in the east of the region. It is gradually becoming recognized as the world's largest wind-power cluster.

The Dongshan wind plant forms part of a 670-megawatt (mW) wind farm operated by China Datang Corp Renewable Power Co, one of many State-owned wind-power developers.

Dongshan has an installed capacity of 250 mW and has erected 158 wind turbines, each with a capacity of 2 mW, produced by Vestas Wind Systems AS, a leading Danish turbine manufacturer.

The plant generates approximately 650 gigawatt hours (gWh) of power annually. That energy is sold to Northeast China Grid Co Ltd - one of five subsidiaries of the State Grid Corporation of China -through three dedicated transmission lines and a series of substations.

Five years ago, the project was at an impasse. Its developers - the State-owned China Datang Corp, Kyushu Electric Power Co and Sumitomo Corp of Japan - had secured site-development rights, but banks were unwilling to take a risk on the project. The bankers were concerned about the high level of upfront capital expenditure for what was then a relatively new technology in China, and also by the absence of any long-term power-purchasing agreements.

Lured by the huge market potential, Kyushu Electric entered into partnership with Datang to build part of the plant, even though the investment return from wind projects is much lower than that from coal-fired plants, according to the Japanese company.

As one of the few foreign players in China's wind-power market, Kyushu Electric has witnessed the sector's development almost from scratch.

|

A wind farm in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region. Transmission and grid connection problems resulted in 2.8 billion kilowatt-hours remaining unused in the first six months of 2010. Zhang Ke / for China Daily |

Almost non-existent until a few decades ago, China's installed wind-power capacity has doubled every year since 2005. It increased more than 10-fold from 28 mW in 1996 to 42 gW by the end of 2010, although the share of wind power in the national energy resource is still small.

"Our concern now is that better placed wind sites have been taken by developers, leaving those with relatively poor resources for the later arrivals, which gives investors less return on investment," said Aoyagi Tetsuji, the Japanese head of the joint project.

The Dongshan plant is China's first and only model wind farm - that is, one deemed "grid-connection friendly" - to have met the technical requirements for grid compliance, according to the director, surnamed Bao.

The farm has installed an advanced wind-power forecast system, which can predict potential disruptions and fluctuations in the amount of power available as far ahead as 48 hours.

The other reason that the plant is so "grid-connection friendly" is that all the turbines have a Low Voltage Ride Through (LVRT) capability, a function absent from most wind turbines in China until two major malfunctions earlier this year caused 1,346 turbines to become disconnected from the grid.

LVRT refers to the capability of turbines to maintain continuous operation during and after precipitous dips in voltage, allowing the power grid to be adjusted quickly and improves overall safety and stability.

Efficient operation of the grid requires that a balance between generation and consumption must be constantly maintained to avert the possibility of disturbances in the quality and supply of power.

Major mismatches or interruptions could lead to a system breakdown and power blackouts.

The increasing number of variable renewable-energy systems feeding the grids poses challenges for the system's operators, who have to deal with unpredictable net-load variability and then balance the fluctuations.

LVRT was not compulsory in China until July 8, when the NEA ordered all wind farms to install the system - which costs 1 million yuan ($157,000) - by the end of this year.

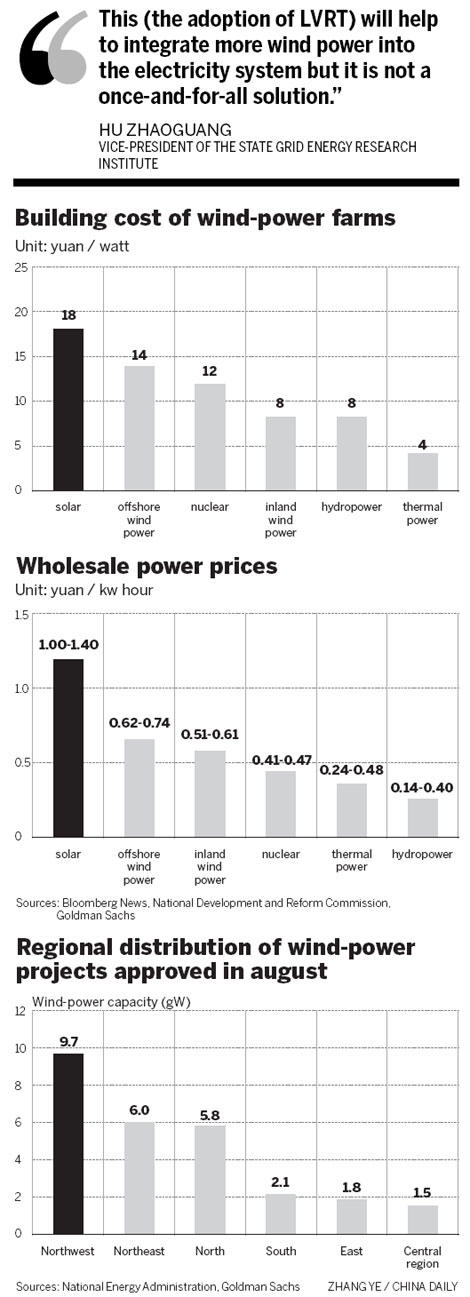

"This will help to integrate more wind power into the electricity system but it is not a once-and-for-all solution," said Hu Zhaoguang, vice-president of the State Grid Energy Research Institute.

Even with these connection-friendly characteristics, the Dongshan plant still had 20 percent of the power it generated disconnected from the grid in 2010, according to Chen Zixin, the deputy general manager of Datang (Chifeng) Renewable Power Co.

A company has to meet all the various conditions required by the State Grid in order that the energy it generates can be purchased in total, according to Chen, who added: "The construction of the grid network lags behind wind-power development."

The weak grid has been cited as the main cause of wind-power disconnections in China.

According to a report by the State Electricity Regulatory Commission (SERC), insufficient transmission capability and poor grid connections resulted in 2.8 billion kilowatt-hours remaining unused in the first six months of 2010.

The SERC report said that areas with abundant wind-power resources account for 75 percent of unconnected wind-power generation in the country because of the lag in grid construction.

China's wind-power resources are concentrated primarily in Inner Mongolia and the northwestern provinces and regions, such as the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region and Gansu province. However, most of that energy is consumed in the heavily populated coastal areas, according to the 2010 China Wind Power Outlook published by the Global Wind Energy Council.

China's largest power distributor, State Grid, which is in charge of distribution in 26 provinces, plans to spend more than 500 billion yuan upgrading the grid during the 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-2015). That's 25 times higher than the amount the distributor spent during the period of the previous Five-Year Plan (2006-2010).

In the west of Inner Mongolia, where electricity distribution is managed separately by an independent local power distributor, the discrepancy between supply and demand is more obvious.

According to Western Inner Mongolia Grid Co (WIMG), which manages 60 percent of the power generated in the region, 42 percent of wind turbines are idle because of insufficient transmission channels.

This is partly because the power generated within the company's jurisdiction can only be exported to other provinces through transmission lines operated by State Grid.

There is little incentive for State Grid to bridge the transmission gap between its area of operations and that of WIMG, despite the fact that the latter accounts for 20 percent of national wind-power generation.

The inconsistency between the growth of the wind farms and the development of the grid network is also partly due to the lax control of approvals for wind projects.

"Local governments are authorized to approve small wind projects which could bring them direct economic benefits," said Hu of the State Grid Energy Research Institute.

On the road between Chifeng city and the remote wind farm, sit row upon row of recently constructed wind turbine factories.

The world's leading turbine companies, including Goldwind Science & Technology Co, Sinovel Wind Group Co, Gamesa Corporacion Tecnologica SA of Spain and Denmark's Vestas, have all established manufacturing bases around the large wind-farm clusters in the area.

Wind projects below 50 mW only require approval at provincial level, and it is estimated that 93 percent of China's wind farms are approved by local governments.

However, in a bid to coordinate the industry, the NEA is planning to tighten the approvals process for wind projects.

China's wind-power sector has developed too quickly, making these problems inevitable, according to Hu of the State Grid Energy Research Institute.

The country is pursuing the development of wind energy with the same determination it has exhibited in its quest for economic growth.

The national renewable and nuclear energy targets have recently been updated by the NEA. They now stand at 150 gW of installed wind capacity by 2020, along with 20 gW of solar, 380 gW of hydro and 80 gW of nuclear.

The NEA plans to increase non-fossil fuel energy to 15 percent of total primary consumption by 2020. These targets are additional to the country's goal of a reduction in energy intensity of between 40 and 45 percent by the same year.

This implies that wind-energy generation should increase by an average of 12.5 gW every year through to 2020, according to the International Energy Agency.

Apart from the issue of grid access, which has improved in the past two years, the biggest challenge for producers revolves around "softer" aspects. These include securing the human resources to support the rapid expansion of the industry and the upgrading of the existing plants in the operation, according to Hisaka Kimura, a senior investment specialist at the Asian Development Bank.

China Daily

(China Daily 11/28/2011 page13)