Food crisis in Asia

|

|

|

Editor's Note:

As the global population rises, farmers, particularly in developing countries, are coming under pressure to increase their crop yields to meet growing demand. D J Clark looks at the problems facing farmers and consumers in different parts of Asia, and examines some of the possible solutions.Naryana Reddy farms a 1.5 hectare plot of land just outside Kothapally, a village in central India. He is typical of the millions of small-scale farmers across Asia who have increased food production at a faster pace than the growth of their families. When Reddy inherited the land he had to support just four people. Now there are seven in his family, but by using better water management, fertilizers and insecticides he gets two harvests a year instead of one and has managed to double his crop.

Over the past 40 years the global population has grown by 80 percent, but food production has more than kept pace, leaving every man, woman and child, on average, with more food than they ever had before, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

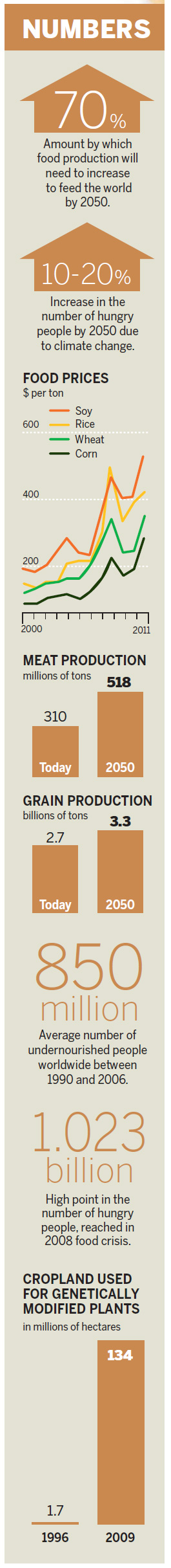

The FAO predicts population growth is slowing down and by 2050 should have almost reached zero, but not before adding another 2.5 billion people to the global population, 60 percent of whom will live in Asia.

Much of the vast increases in food production came in the 1970s in what was known as the "green revolution".

"If you look back through the annals of history you will see that science has made a very important contribution to agriculture," said Clive James, director of the International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications.

"People forget that Norman Borlaug, the architect of the 'green revolution' received the Nobel Peace Prize for saving 1,000 million people from hunger by creating new seed variations and advocating the use of fertilizers and pesticides to increase yields."

The "green revolution" started well with crop yield increases far outstripping population rises, but at some point in the 1980s crop yield growth rates started to fall and in 1990 the food production growth rate dropped below the population growth rate.

There are other factors at play that are also reducing farmers' ability to produce food: Climate change is starting to have an impact on crop yields. The International Food Policy Research Institute ran a series of scenarios on climate change. All of them led to lower crop yields by 2050.

"With climate change comes the problem of water scarcity and higher temperatures," said William Dar, director of the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics.

"Today models are already indicating decreases in crop yields and we need to find ways to bring that productivity back up in order to feed 9 billion people by 2050."

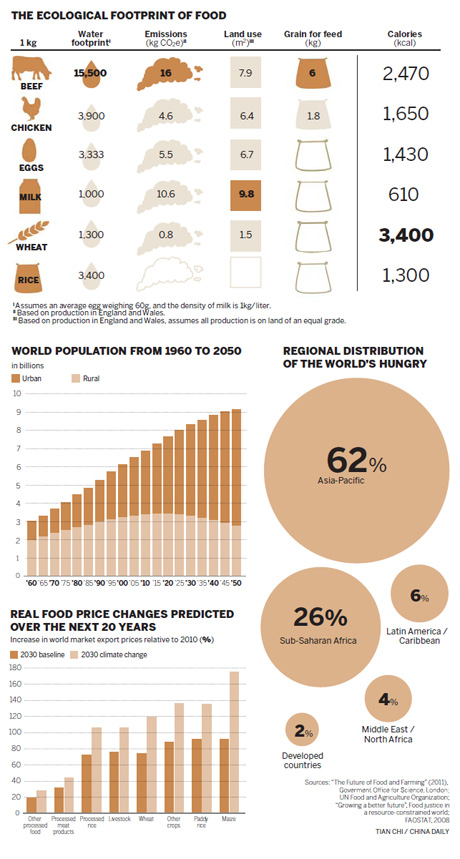

Growing demand for meat is also putting pressure on the world's water resources.

In the next 40 years the demand for meat will double, with every kilogram of meat using eight times the water that is needed to produce 1 kg of wheat.

As populations rise and farmland becomes increasingly scarce, more rural poor are moving to cities to find food and jobs.

In cities, where there are no shortages, the big problem confronting the poor is that food is too expensive.

Mohammed Mohasin lives in a slum on the outskirts of Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh.

Finding it almost impossible to make ends meet in the countryside, Mohasin moved to the sprawling city of 7 million in search of a better life.

Compared to many Bangladeshis, this father of two has done relatively well, as he has a stable job.

But in spite of this, his ability to feed himself and his family is out of his control.

Standing in the small gap between his tin-roofed home and an encroaching open sewer, he explains why he is skipping his lunch.

"When food prices go up I first have to reduce our expenditure, try to search for cheaper foods and reduce our eating from three to two meals a day."

Like many of the urban poor across Asia, Mohasin spends almost 90 percent of his income on food and rent, leaving him little flexibility if food prices soar as they did in 2008.

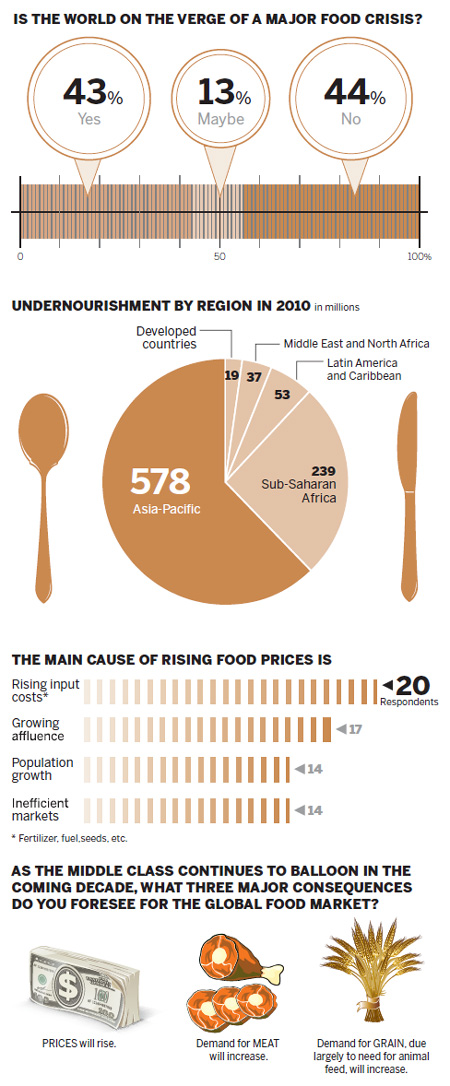

The World Bank estimated that an extra 100 million people went hungry around the world in that year due to food price increases.

Most analysts predict that food prices will more than double again over the next two decades.

Whereas the rural poor have opportunities to collect food from other sources such as open ground, forests and rivers, those that live in cities are dependent on global market fluctuations.

Professor Cai Jianming from the Chinese Academy of Sciences is a world leader in developing urban farmland, ensuring that Chinese cities have the means to meet all of their vegetable needs within their municipal boundaries.

"In southern China we can use rooftop spaces, but in the north it is easier to create spaces around built-up areas where the distance food has to travel to markets is relatively short. Vertical gardens, using domestic balconies to grow edible food, are also gaining popularity in Beijing," Cai said.

Historians often point to the fact that most famines are not caused by a lack of food but bad governance.

In 1996 the FAO estimated that the world was producing enough food to provide everyone with 2,700 calories a day, 500 more than is needed by the average human.

But out of the world's estimated 7 billion people, 1 billion are clinically obese while 1 billion remain malnourished.

Professor Paul Teng from the Center for Non-Traditional Security at Nanyang Technical University in Singapore has been studying losses in the food production, distribution and consumption systems and estimates that 50 percent is lost before it reaches our mouths.

"In other words, if we could just recover the losses we would have more than enough food," he said.

In looking at how to address the potential food deficit, a recent report from British NGO Oxfam posed a simple question: Is the answer to our future food needs to produce more food, or is it to try and fix our broken food system?

Bas Bouman, head of crop and environmental sciences at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines believes doubling rice yields in Asia over the next 40 years is not an impossible task.

"If you look at current rice varieties that have been produced since the 'green revolution' era, their yield potential is 8-10 tons per hectare, but the average yield here in the Philippines is 3.7 tons. In Thailand, a major rice exporter, the average yield is just 3.5 tons per hectare. In these countries there are tremendous opportunities to increase yields with better management without taking into account new seed variations."

A combination of better water management and engineered crops was the answer given by many scientists, though biotech farming is not without its critics.

At the University of Philippines Los Banos, Professor of Crop Science Ted Mendoza demonstrated how combining drip feed irrigation, water harvesting, intercropping and organic manures can have equally impressive results without the need to spray insecticides or genetically modify the seeds.

The Oxfam report suggests returning to traditional agricultural practices is "dangerously romantic" in the light of the looming crisis, but Mendoza refuses to accept the crisis exists.

He believes the scare is manufactured by the agribusiness industry, which he claims is the main beneficiary of commercial fertilizers, insecticides and seed variations that farmers are encouraged to buy to increase yields.

(China Daily 08/01/2011 page10)