It's important that media analyze their role

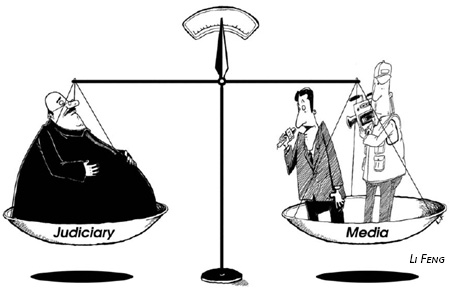

A regulation issued by the Supreme People's Court (SPC) recently says that the people's courts should accept media supervision. But the regulation also says that journalists could be penalized if they distort facts of or file partisan reports on ongoing trials - especially if they could prevent justice from being delivered and/or violate the law.

The regulation first has to be appreciated, because it represents great progress both in terms of concept and institution. The SPC has reconfirmed the basic standards of judicial reports and comments in the media are objectivity, balance and impartiality, which are recognized codes of journalism worldwide.

In terms of institution, too, the regulation is a big step toward press legislation and managing the media by law.

Besides pledging to improve media supervision, the regulation states five situations under which journalists could be charged: partisan coverage of ongoing cases with malicious intentions, disclosure of State or business secrets, impairing national and social interests, soiling the reputation of judges or people involved in lawsuits, and obstructing trials and judicature or conducting any other activities that may prevent justice from being delivered. It seems that the regulation emphasizes supervision of media reports, which is questionable.

China has entered the era of mass media with more than 1 billion TV viewers, over 200 million newspaper readers, more than 700 million mobile phone users and about 360 million netizens.

President Hu Jintao recognized last year that the Internet and metropolitan media are among main types of media in China. The metropolitan media represent elite opinion, while the Internet gives space to public views.

These two have cultivated the practice of media supervision and expedited the process of media-driven civic participation, which has been exerting more and more pressure on the administration for supervision of justice.

In countries that have relatively better rule of law, "trial by media" is restricted by law, ethics and the media industry itself - in other words by society as a whole.

When it comes to countries like China, where the rule of law is not fully developed, public power and corruption sometimes prevents justice from being delivered. But to maintain social fairness and deliver justice is the common pursuit of China's judiciary and media.

The SPC has been committed to promoting judicial openness and accepting public supervision. And with the progress of China's legal system and media specialization, the overall relationship between the two is likely to become affable.

Theoretically, the most important thing in a legal case is a fair trial. But for that the judiciary has to have specialization and gain credibility. And till such time that it acquires the two traits, public criticism cannot be avoided.

"Trial by media" is indeed a phenomenon in China, and if we analyze different cases thoroughly, it will be evident that the positive role played by the media far outweighs its negative effects.

Cases that are prone to cause conflicts between the judiciary and the media usually reflect the most acute social contradictions, such as the conflicts between the public and officials and the widening gap between the haves and have-nots, which are behind the dissatisfaction of the people. People are worried about rampant corruption and the nexus between government officials and businesspeople, too.

So while covering cases involving officials and the public or the rich and the poor, the media usually pay more attention to the public or the poor.

Besides, if key facts of a case are controversial or not disclosed effectively in court (and to the public), the situation tends to become more volatile.

The concept of "trial by media" comes from the West. It refers to reports and comments published or aired by the media during legal proceedings that could influence adjudication and the outcome of a case.

Readers' letters, commentaries, investigative reports, photographs, cartoons, TV images and any other form of communication could constitute "trial by media".

Media reports and comments on legal cases have increased rapidly in China over the past decade or so, and so have concerns over and criticisms of "trials by media".

Xu Xun, director of the legal department of the Central People's Broadcasting Station, says the country indeed witnesses "trials by media".

Its manifestations can be seen in sensational reports and exaggeration of facts, just one of the parties in a lawsuit to getting a chance to express opinions, use or discard of interviews according to predetermined notions, out-of-context or even distorted reporting of interviews, speculation on the outcome of a trial that could influence public opinion, assessment of the quality of cases and "conviction" of defendants before the trial ends in court, publication or airing of critical comments and groundless accusations, and labeling of indiscriminate charges on others.

These phenomena that constitute "trial by media" and contradict the spirit of law are indeed on the rise and pose some threat to justice.

But, as Xu argues, acknowledging the existence of "trial by media" does not mean it has become all-pervasive. Not all reports and comments published and aired by the media on a case can be considered part of the "trial by media".

If such a criterion is applied then it will inevitably lead to unreasonable restrictions on freedom of expression and the public's right to knowledge.

With the help of laws, regulations and practices, Xu suggests the media follow 10 self-disciplinary rules while covering a judicial case: It should never brand anyone guilty before the court passes its verdict; it should refrain from making partisan comments against any of the parties when they exercise their rights; pay special attention to the rights and interests of minors, women, senior citizens and the physically and intellectually challenged; not publish or air detailed reports on cases related to State and business secrets and personal privacy; not spy on judicial activities; not become the spokesperson of any party; pass comments only after a verdict; limit queries and criticism before a verdict on activities that violate judicial proceedings; not target critical comments on the morality and knowledge of judges; and not comment on lawsuits involving its own media outlets.

The author is a professor of media studies in Beijing Foreign Studies University.

(China Daily 01/11/2010 page9)