Still waters

|

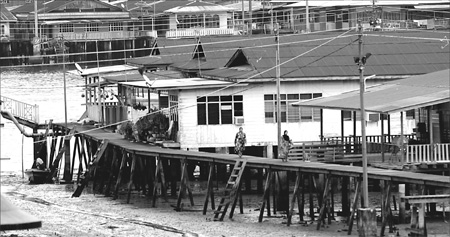

A view of Kampong Ayer. Courtesy of the Brunei Times |

Kampong Ayer in Southeast Asia's Brunei, is a sea of tranquility, frozen in age-old traditions. Zhang Jin reports

A 15-minute drive from Brunei's airport is the quay to the world's largest water village, a place that is home to one tenth of the country's population of 390,000.

The Brunei River protects the water village, locally known as Kampong Ayer, from the bustle of the capital, Bandar Seri Begawan.

On the bank opposite the village, just two minutes by a spear-shaped speedboat, is a three-story up-market shopping complex. Further afield are apartment blocks and bungalows with lush green gardens and modern amenities.

A good starting point for a walk around Kampong Ayer's warren of seemingly slum-like houses and footbridges is the gallery that stands where Kampong Ayer's largest primary school once stood.

Relics exhibited in the first two halls of the Kampong Ayer Cultural and Tourism Gallery bring back memories of China.

Porcelain and china-ware salvaged from the sea or unearthed from the soil, some broken, show that trade between the two countries dated back as early as the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Other halls show the village's links with the West and its customs.

Indeed, people have lived in Kampong Ayer for more than 1,300 years, as it was the trading center on Borneo Island that also includes today's Indonesia and East Malaysia.

Handicrafts used to be Brunei's major exports for centuries until oil was discovered in the 1920s.

Just as I wonder if traditional skills are still alive, I find my answer in the center of the gallery. There, at a wooden spinning wheel, sits Hjh Siti Aidah Pengarah Dato Paduka Hj Othman, who swiftly spins the threads for her co-worker to weave into cloth.

She is the fifth-generation inheritor of a tradition that some believe came from China. She tells me through an interpreter that traditional weaving continues to flourish in some parts of Kampong Ayer even today.

"My family has been using this kind of wooden spinning wheel for more than a century," says Hjh Siti Aidah, 60. She was born into a family of weavers in Kampong Ayer and mastered the skills by watching her parents.

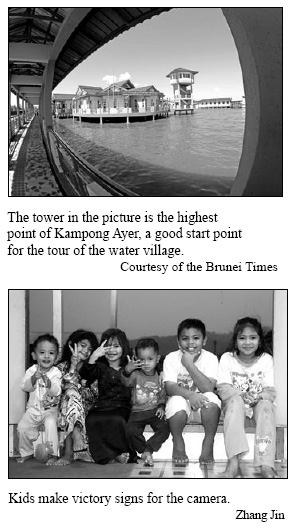

Outside the gallery's exhibition center stands a watch tower, offering a bird's-eye view of the village.

Atop the tower, I see several blocks of houses on stilts, old and new, scattered across the river. Each block comprises a few smaller villages that constitute Kampong Ayer.

Its peace is disturbed only by the humming engines of the speedboats snaking their way between the clusters of houses.

Descending from the tower, I board a speedboat, or water taxi, as the villagers call it. A 2-minute trip that costs 50 Brunei cents (1.5 US cents) takes me to KG Setia A, one of the oldest and best kept villages of Kampong Ayer.

The wooden walkway that leads to the home of Hj Sucaiman Teripin, is flanked with restaurants and shops.

The shabby outward appearance stands in stark contrast to the interior of the house that has all the modern amenities including air-conditioning, satellite television, Internet access, plumbing and electricity.

These wooden houses, that date back many years, use a special wood sourced from the surrounding forest that can stand in the water.

The 101-year-old Teripin built his house in the 1930s and his family has lived there since then.

He has plenty of stories to share of his century-old life.

He recalls how a friend was shot dead by a Japanese soldier simply because he had uprooted a plant the soldier claimed had been grown by the Japanese army, which occupied Brunei during World War II.

"Blood spewed out; I was shaken," Teripin says.

The Japanese finally left, and Teripin's family began to prosper.

His 13 sons and daughters have given birth to more than 100 children. Teripin also has 50 great grandchildren.

Some family members have now moved to the city, but "most of them stay because they love this land".

Hj Suhardi Hj Agaj, one of Teripin's grandsons, is one of them.

The 34-year-old says a lot of changes have occurred since the time of his grandparents. Modern recreation such as watching TV and movies has replaced old ones such as chatting. There are more cement houses now than wooden ones. Fewer people eke out a living from fishing and handicrafts and more are finding city jobs.

"But I won't leave. Here, you can buy an engine (for the boat) and go anywhere. I can catch fish for a living, though I cannot make a fortune. Life is good enough," he says.

Since the 1960s, the government has been improving the infrastructure and services in the water villages such as providing piped water, sanitation and sewage facilities.

But in Teripin's home, traditions remain alive.

His great grandchildren gather around us. They touch their foreheads to the back of my hand, in a traditional greeting to someone older. They bend whenever passing by me, another show of respect.

Timid, they flee whenever I raise my camera to take a picture. "They seldom meet outsiders, let alone a man from China," Teripin says.

But a while later, they do get acquainted with me and pose freely.

On the boat back to the city, however, the garbage deposited by high tides on the bank of the river reminds me of how modernity has gradually changed the life of the village.

Many residents still throw garbage out of their windows and into the river. In the old days, when most rubbish was organic, this did not pose a health or environmental risk. But now, plastic bags and cans will remain floating if not removed.

Traditions are also weakening, especially as the younger generation, yearning for a more exciting life, starts to move out of centuries-old dwellings.

Muhammad Lutfi Hj Abd Majid, 18, is one of those who wants to move out, saying he is fed up with the poor accessibility of the village.

He parks his car on the banks of the river before reaching home by speedboat. "Finding a parking lot is always a problem."

In all honesty, it is Kampong Ayer's tranquility that strikes me. Being part of Kampong Ayer cuts one off from urban life.

In contrast, in Zhouzhuang, East China's Jiangsu province, hawkers bother you soon as your arrive at the docks. In Fenghuang, Central China's Hunan province, girls in Miao ethnic dresses follow you for a photo - and a picture costs 10 yuan ($1.50). In Tai O of Hong Kong, the shops and restaurants hum with tourists.

But in Kampong Ayer, the residents, though intrigued by the presence of an outsider, do not bother you. They are glad to answer questions and willing to take photos with me - free of charge.

My guide tells me the government plans to promote the village as a tourist attraction. Efforts will include enhancing people's English proficiency and providing homestay services to attract more holiday-goers.

There may soon be a day when there are no more old folk weaving and fishing in Kampong Ayer and hordes of tourists descend on it to destroy its peace. But for now, its tranquility remains for all to enjoy.

(China Daily 01/01/2010 page9)