The king and I

|

Alai is the country's most famous Tibetan writer who writes in Chinese. Main photo by Feng Yongbin |

When he was a shepherd in the remote mountains bordering Tibet autonomous region and Sichuan province, Alai hoped eagles wouldn't come to grab the sheep and wolves would stay away.

Today, the famed Tibetan writer hopes his novels and poems can help the world better understand his, sometimes, misunderstood people.

"As an intellectual, I want to express myself in my own voice and try to say only the truth," says Alai, whose latest offering, King Gesar, was launched worldwide last week as part of the Myth Series initiated by Canongate Books.

Word spread in 2003 that he'd join the Myth project and write King Gesar, the most famous Tibetan epic. However it wasn't all smooth sailing.

The author was already writing Hollow Mountains (Kong Shan), a 3-volume realistic work on six Tibetan villagers' fate against the fast-changing rural landscape.

It was another heavyweight effort after his first successful novel Red Poppies (Chen'ai Luoding) was published in 1988.

Another obstacle was the sheer scale of the project - previous novellas in the project had been less than 200,000 words but this limit was not enough for King Gesar - with 1.5 million lines and more than 2,000 years of history.

King Gesar is now the world's longest and most intact epic of its kind about the Tibetan king.

"I won't build a 'dinosaur skeleton', or cut my own toes to fit smaller shoes," jokes Alai, a short, stout chain smoker with a deeply sun-tanned face.

King Gesar, a subject on history, offered Alai great joy in writing.

The most striking feature is the parallel lives of King Gesar and ballad singer Jigme, both in search of their destinies.

King Gesar is reputed as a "living" epic because ballad singers still chant the songs in local villages.

|

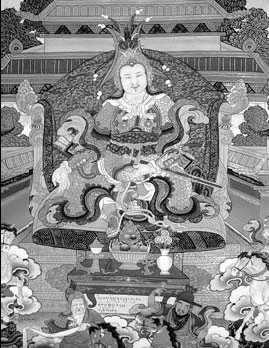

A portrait of King Gesar. |

In these ballads, most of the storytellers are farmers or herders who wake up from a dream and suddenly begin pouring out eloquent lines about the King's birth, his battles and his return to heaven.

Alai visited a dozen ballad singers as he searched for places where the King was said to have left footprints.

"A writer should not be content with books and second-hand information, he must visit the field to find solid details," Alai says.

In his novel, Jigme also journeys across the plateau, doggedly searching for such sacred sites and dreaming of King Gesar's growth from a gifted child to a mighty king.

"The ballad singer dreams of parts of King Gesar's life and comes out to reality. That works like a pair of scissors cutting out the most interesting parts from the colossal epic," Alai says.

While sorting out information seemed to be a major task in this novel, Alai admits he faced other complexities in the early days of writing.

Growing up in a rural family where the spoken Tibetan dialect is very different from the language in Lhasa, Alai didn't study written Tibetan, either.

He had to decide if it was worthwhile to write in Chinese on the Tibetan subject.

In the early 1980s, foreign literature became more fashionable in China and Alai guided himself through classics by Hemingway, Tolstoy and other world masters while learning to drive a tractor before becoming a middle school teacher.

When he joined amateurs in a writing training session, all they heard was the political meaning of literature and the young man was quick to question. "That can't be right," Alai suggested.

Eyebrows were raised and a local celebrity writer challenged him to write something.

He was in his early 20s, and worked late into the night to write his first poem in Chinese. He can't remember its content, the soft-spoken 50-year-old smiled, recalling that many praised his maiden work.

However it was Czesiaw Miiosz (1911-2004) and other Jewish writers who had to leave their European hometown for America who helped him decide to become a writer.

"They left their kinsmen and lived in a different culture," he says. "They helped me answer the question: Would writing in a different language make sense at all?"

The choice was Chinese.

Alai poured all his energy into Red Poppies, a book based on legends in his hometown, where the Khampa Tibetans have lived in diversified cultures for centuries.

For four years publishers rejected Alai's work, but it eventually was published, has remained a bestseller and has been translated into 16 languages.

At the height of his writing career, Alai surprised many by turning to run a science-fiction magazine based in Chengdu, Sichuan province, and successfully turned it into one of the world's leading science ficition magazines with a circulation of 400,000 in just a few years.

"I'm curious about things I don't know. But once you get to know all the routines, it's boring," Alai says.

His burning desire to write returned during a vacation in Japan. He left the touring team and locked himself in the hotel room. Payment for the novelette didn't even cover one day's cost at the hotel, but it was a sign the writer in Alai was coming back.

In China's old planned economy, it was almost impossible to change careers but Alai says he doesn't plan his life and is grateful for his different professions because they enriched his life as a writer.

"Whatever profession I take up, I do my best to excel," says the writer, who became chairman of the Writers' Association in Sichuan earlier this year. Alai hopes that readers could see Tibet as it is, instead of what they imagine it to be.

When he was promoting Red Poppies, he met a reader in Switzerland who argued that Alai shouldn't have written about killing and cruelty, as "Tibetans all believed in religion".

"That man's gone nuts," Alai shrugs his shoulders. "You'd find such people everywhere."

But for most readers, Alai suggests they drop assumptions and even biases, before they begin to understand what he is trying to say.

The author strongly opposes the idea that Tibetans should persist with their primitive lifestyle for the sake of so called "cultural protection".

"Ask a shepherd if he'd go for a job without any cultural color for a monthly pay of 3,000 yuan ($439). I bet he wouldn't stick with the herding that brings him 200 yuan just to protect his culture. "No one has the right to prevent the common people from seeking a better life."

As always, when the book was finished, Alai revisited the places that he portrayed as the story's background.

"Writing is always emotional for me. I need time to return there, meditate and calm down. I need to empty myself before the next work can bud," he says.

"Books are like humans: Some are luckier to find good translators and marketing agents. But there are always best-selling average books and little-known quality books."

(China Daily 09/07/2009 page8)