Reeling in the years

|

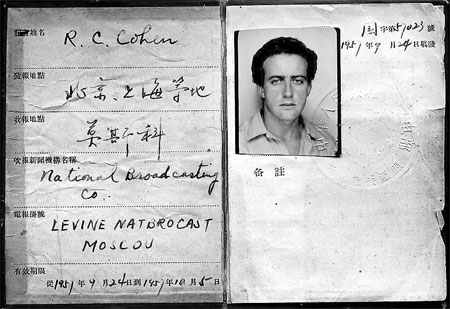

A press credential issued to Robert Carl Cohen in 1957 by the Chinese government. |

On Oct 1, Tian'anmen Square will be the focal point of China's 60th anniversary celebration, and revelers are sure to jostle for the best position to watch the fireworks overhead.

In the same place 52 years ago, Robert Carl Cohen, a 27-year-old psychology student from the United States, stood transfixed by the magical spectacle.

"That was the high point of my filming in China," says the veteran documentary filmmaker, who turns 79 next month.

He was referring to the climax of a journey that brought him to the heart of a young country and his own voyage of self-discovery. It began on Aug 21, 1957, when Cohen and 41 other Americans arrived in Beijing after a nine-day, 9,650-km trip on the Trans-Siberian Railway linking China and the Soviet Union.

They had been invited by the All-China Federation of Democratic Youth, while attending the 6th World Youth Festival in Moscow that summer. As if going to Moscow was not enough to arouse suspicion for an American at the height of the Cold War, venturing to Beijing effectively violated the US State Department's travel ban, which prohibited any physical contact with an "enemy country".

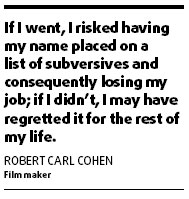

"If I went, I risked having my name placed on a list of subversives and consequently losing my job; if I didn't, I may have regretted it for the rest of my life," says Cohen, whose previous experience of China consisted mainly of a distant view of Madam Chiang Kai-shek, who visited his junior high school in Los Angeles as part of a Kuomintang "money-raising" effort in 1944.

The dilemma ended as Cohen boarded the train. Having agreed to film his journey for NBC television, Cohen submerged himself in the sounds and sights of a strange land for the next two months, traveling north to south and filming freely scenes that had not been captured by a Western movie camera since the founding of the People's Republic, nearly 8 years earlier.

Asked how he was able to do this, given the degree of political censorship that existed in China then, Cohen said he believes he must have received high-level help.

|

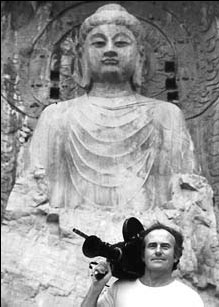

With a camera on his shoulder, Robert Carl Cohen stands in front of the Buddha Statue in Longmen Grottoes in Luoyang, Henan province in 1978. |

"My guess is that someone in a very senior position within the Chinese Foreign Ministry - possibly (premier) Zhou Enlai himself - was interested in enabling me, and the other group members working for the US press, to report to our public back home."

Whatever the source of his good fortune, the credentials given to Cohen carried him far and wide. The rare black-and-white footage, shot with a 16mm hand-wound Bell and Howell Filmo, was later edited into a 50-minute documentary film narrated by Cohen and titled Inside Red China. It can now be seen on YouTube.

A dashing Cohen opens the show, asserting his and his fellow countrymen's right to know, while admitting that without living in China for years, "even the most observant reporter cannot experience the daily joys and sorrows which are most important to the average man".

However, he made a determined effort to delve into those lives and to share their stories, happy or sad. With the tender heart and unfailing eye of a curious young man, Cohen captured on film moments and details that elude even the most seasoned journalist.

On several occasions, small children reached over and pinched the hair on his forearm. Cohen was told they were wondering if he was "some sort of monkey". And everyone wanted to see the monkey - in the film, laughing children can be seen besieging Cohen's car as he beats a hasty retreat.

Other touching images include an old man proudly showing how his smoking pipe worked in front of a bemused audience, and fully-clad bathing beauties "shy of the sun", on the beachfront in Dalian.

Cohen was surprised to see the Peking Opera-going public dressed "in a more proletarian manner", while "when it visited London or Paris, people wore diamonds and furs".

"In the West, white is the color for purity, while in Chinese theater, a patch of white makeup in the center of the face represents dishonesty or foolishness," says Cohen, whose journey at times turned into a crash course in Chinese symbolism.

In the documentary, a classic Peking Opera in which a rebellious Monkey King triumphs over heavenly gods, is shown as an intended metaphor for "the people's victory".

Yet the biggest contrast captured by Cohen's lens is the seemingly contradictory beliefs and ways of living that had come to exist in one culture. During his visit to the Beijing Children's Hospital, Cohen noticed a new X-ray department, located right next to the acupuncture room.

Inside factories and shipyards, less-than-skillful administrators operated Soviet-supplied modern machinery. While vessels as large as 10,000 tons were being built, workers were seen hand-hammering the giant hull into shape.

Given the speed of growth, it was no surprise for some Western economist to predict then that "within 10 years, China will become the third-biggest industrial power, right after the US and Russia". Cohen was understandably impressed, but unflinching in delivering the occasional qualms.

"There were times when our visits to industrial facilities had to be canceled because the workers there were participating in 'struggle meetings' to denounce 'negative tendencies'," he says, referring to the fomenting political movements which less than a decade later culminated in the devastating "cultural revolution" (1966-76).

Acute observations aside, the young Cohen also demonstrated a rare flair for journalistic objectivity. While describing the strict rationing system of the time as "limiting everyone to a very small amount (of food)", he also points out that it "enabled even the poorest people to get meat, which they couldn't afford before".

Unlike his predecessors who years earlier traveled to Yan'an to meet leaders of the Chinese Communist Party in their cave dwellings, Cohen and his fellow travelers were invited to a reception given by premier Zhou, whom he describes as "moderate, intelligent, and a pragmatic realist".

"Although the questions and answers were being translated from English into Chinese, on several occasions, the premier, apparently understanding English, responded to the questions before it was completely translated," recalls Cohen.

As a young American fresh from serving in the army in Germany and France, Cohen was naturally drawn to "sensitive" things. Inside an automobile factory in Changchun, the cameraman spotted US-made machines despite the complete trade embargo by the US government, and inside the Nanjing University library, were books with titles including Applied Atomic Energy and Air Navigation, the latter published by the US Navy only a few months before.

But it was the anti-US propaganda posters that proved the most difficult to miss. A typical one that Cohen filmed, shows a helmeted American soldier being surrounded as his jeep gets stuck in the mud.

"I was not shocked at all," says Cohen, whose social psychology studies at the University of California in Los Angeles involved propaganda content analysis. These days, posters purchased on that trip, including anti-US ones, make up a crucial part of Cohen's poster collection.

|

Robert Carl Cohen (second from left) and several of his American fellows in Moscow for the 6th World Youth Festival in the summer of 1957. Photos courtesy of Robert Carl Cohen |

While he was still traveling in China in 1957, his report was sent by plane via Moscow to the NBC headquarters in New York, undeveloped and uncensored. "The average time between my filming a scene in China and it being televised across the States was about one week," says Cohen. "But I was also given transmission time from Radio Beijing, and made several direct radio broadcasts from China to NBC in San Francisco."

While the journey made Cohen's reputation as the first American journalist to film in China since 1949, it was not without consequences. Having failed to take his passport at the airport when Cohen returned to the US in December 1957, the US State Department refused to renew the passport when it expired the following year.

"There was even one married couple in our group who, after we'd left China, contacted the US Un-American Activities Committee and said they were prepared to testify against the 'pro-Communists' in the group," Cohen says.

But he was not deterred. From 1958 to 1965, Cohen gave several hundred film lectures throughout the US and Canada.

"The decision to challenge the dominant view of the Cold War era has led me to a half-century long career of producing films and books which deal with many of the problems afflicting our world, ranging from prejudice to discrimination and fear-mongering," says Cohen, who is today among America's most respected documentary filmmakers.

And China remains one of the most compelling subjects. In 1978, shortly after the "cultural revolution" ended, Cohen returned to film what he describes as "a nation that was just crawling into the sunlight after surviving a terrible, long winter".

He returned again in 1988, when he saw himself as "some sort of futuristic time-traveler who popped in to see how things have changed every decade or two".

Back in 1957, Cohen, who was given 11 30.5-m rolls of film - the equivalent of 45 minutes total - for covering the six-week journey, saved the last two for the Oct 1 celebration. Standing in front of Tian'anmen among 10,000 dignitaries and foreign guests, he captured the colorful parade in which children waved pastel paper flowers and thousands of doves were released into the cloudless sky.

"By night the streets of the Chinese capital are aglow," Cohen says in his film narration. "The city echoes to the thunderous roar of exploding sky rockets - the glowing reds, greens, golds and blues silhouettes the skyline and the ancient Forbidden City."

Today, Cohen still relishes his role of bringing China to the Western world.

"I've been lucky enough to witness the building of a mighty nation and the striving of a quarter of the human race for a better world," he says.

(China Daily 08/17/2009 page8)